Dog tags, those small metal plaques hung around soldiers’ necks are so named because of their resemblance to the registration tags worn on dog collars.

A form of dog tag was first worn by Chinese troops during the Taiping revolt of 1851-1866. Both soldiers of the Imperial army and those of the opposing rebel army wore wooden identification badges on their belts. Carved into the badges were the soldiers’ names, ages, birthplace, military unit and the date they first enlisted. It was a remarkably sophisticated system for the time, and it enabled the rapid identification of men killed in battle.

The first use of the term ‘dog-tags’ (Hundemarken in German) was by the Prussian army in 1870. They were subsequently issued to American soldiers in 1906, and to British troops in 1907. The American tags were circular, made from aluminium, and had the soldier’s details stamped into them. They were worn around the neck on a cord.

Those worn by the British consisted of aluminium discs, into which were pressed a series of numbers and letters, indicating the soldier’s nationality, together with his army number and his unit reference and rank. They were also worn on a cord around the neck.

During the First World War (1914/18) all British soldiers wore two tags – one green, the other red. These were made from a compressed fibrous material that made them very light, and more comfortable to wear, particularly in hot weather. When a soldier’s body was found, one of the tags was removed and taken to record the death. The second tag remained on the body to inform burial squads of the man’s identity. American troops also wore two tags but made of aluminium.

Many other nations adopted broadly similar systems.

By the time of the Vietnam War, American dog-tags had become elongated, with rounded ends, more like the commonly used plastic key fobs in appearance. Made from non-corroding metal, the tags contained the person’s last name, first name, Social Security number, blood type, and religion.

Fifty-eight thousand US armed forces members were killed in Vietnam, and a forthcoming art exhibition at the Chicago Public Library will commemorate every one of them.

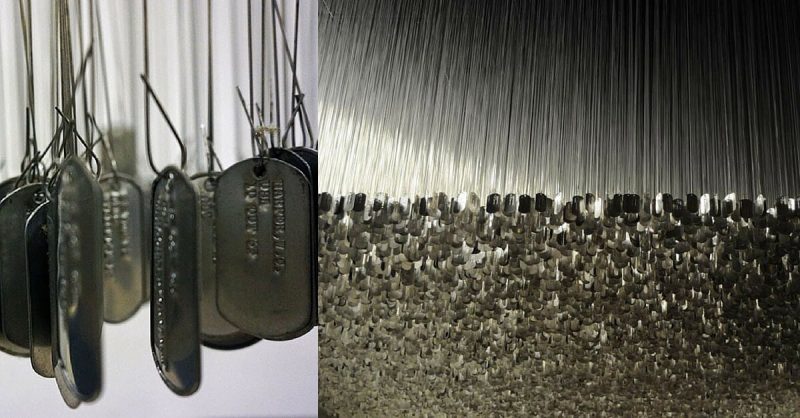

Through an extraordinary effort to understand combat through the eyes of those who experienced it, Chicago Public Library and the National Veterans Art Museum partner to present, Above and Beyond, the 58,000 dog tag art installation created by Veteran Artists, a very important art exhibition reflecting on the meaning and consequences of the Vietnam War.

Above and Beyond features over 58,000 dog tags representing U.S. military personnel who lost their lives in the Vietnam War. Above and Beyond will be featured as an extended exhibition, opening on February 20, 2016, and continuing through April 15, 2020.

Above and Beyond was commissioned by the National Veterans Art Museum and created by U.S. Military Veterans (and artists) Rick Steinbock, Ned Broderick, Joe Fornelli, and Mike Helbing. The exhibit is comprised of hand-stamped replicated dog tags of every U.S. soldier killed in service to their country in Vietnam. The dog tags are suspended from the ceiling of an open 13 ft. X 34 ft. installation, making the impact of combat visible to all.

More information about the exhibition: http://www.nvam.org/

All images courtesy of NVAM.org