Christopher Nolan, a renowned film director, has recently been scouting locations in Dunkirk, fueling rumors that he is to direct a World War II action adventure film in 2016 based upon Operation Dynamo.

Dynamo was the codename given to the operation to evacuate the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and other Allied troops from the French port of Dunkirk in May and June of 1940. When shooting starts in May 2016, Nolan will utilize IMAX 65mm and 70mm large-format film photography. The film will star Kenneth Branagh, Mark Rylance and Tom Hardy.

Operation Dynamo makes a stunning and exciting subject for an action adventure film. The nine days from Monday the 27th of May, 1940 to Tuesday the 4th of June will always be acknowledged as one of the most incredible military events in British history.

For six months the combined British and French armies had faced the German army across the Franco-German border. Along with the French, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) under the command of Lord Gort was equal in number and greater in terms of available artillery and tanks than the Germans.

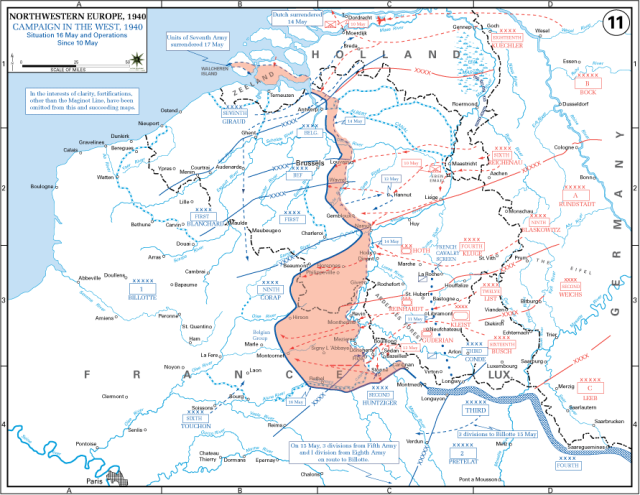

On the 10th of May 1940 the Germans began their push towards the west. Their strategy was to break through the French lines in the Ardennes and then make a concerted effort to get to the Somme estuary, thus splitting the Allied forces in two. They anticipated that the BEF would advance into Belgium, leaving the Germans a clear run to capture the Allied forces.

After just ten days the Germans had pushed the BEF and its French allies all the way back to the French coast, where, at Abbeville, the Germans succeeded in splitting the Allied forces in half. If the Germans had, at that point, turned north along the undefended Channel coast they would have trapped the BEF without a hope of escape.

For the German forces, General von Bock was to go north to invade Holland and northern Belgium, and General von Rundstedt was to undertake the mission to break through the French lines on the Meuse to make a run for the Somme. Rundstedt was well equipped, with an armored group taking the point and followed by three armies.

As expected, as the Germans launched their offensive the BEF and French moved into Belgium, hoping to integrate with the Belgian army and halt the German advance. Within six days the Germans had broken the French lines.

The leader of their panzer division, General Guderian, was given a day to consolidate his position, but instead, he moved forward, arriving at Ribemont on May 17, 1940. The German High Command was incensed, thinking that Guderian had exposed his Panzers to the danger of an Allied counter-attack. This disloyalty infuriated Guderian, who resigned, but General Rundstedt’s cool head prevailed, and he was asked to return to his command.

On May 20th, Guderian took Amiens and Abbeville; the Panzer troops had reached the coast. Right at this point, the Germans were vulnerable to a counter-attack, but it did not come. General Gamelan, the French commander, issued a belated command to break out south, which was exactly what the Germans feared. But luck was on the German side, and before the order could be executed, Gamelan was replaced by General Weygand. Weygand refused to issue any orders until he had visited the front; this gave the Germans three valuable days to make their own plans.

At this time, Lord Gort signaled the need to evacuate troops from Calais, Boulogne, and Dunkirk, and the British War Office was considering this need. Admiral Bertram Ramsey was appointed to take command of the operation, dubbed Dynamo, and on the 20th of May, he held his first meeting. Ramsey had immense challenges to overcome. He had access to a very sophisticated fleet from the Royal Navy, but there was a problem – the waters around Dunkirk were so shallow that the large destroyers that he had access to had to moor offshore.

Therefore, Ramsey had to find a way to get the troops off the beach in small boats that could ferry them to the larger ships. He could not use the inner harbor at Dunkirk, as it had been destroyed by uninterrupted Luftwaffe bombing. Once he got the troops back to Dover, he had more logistical issues with which to deal. He only had eight berths to use and once off the ships the men had to be transported away from the dock, fed, and housed. He optimistically hoped to rescue 45,000 troops.

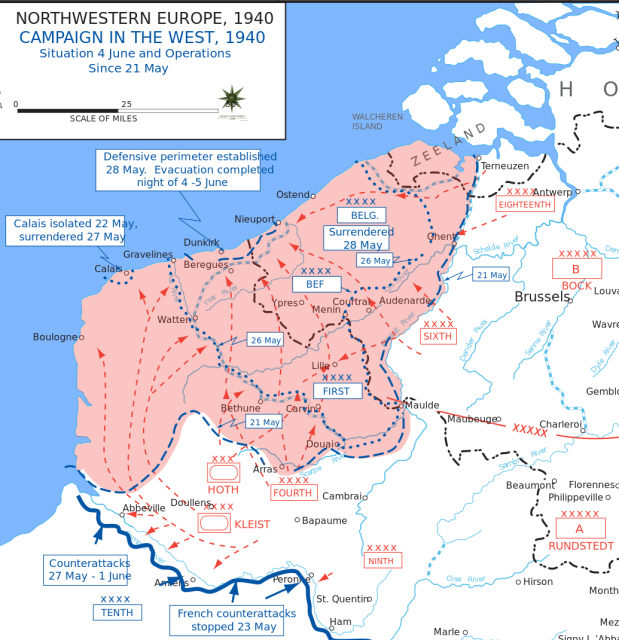

On the 21st of May, the Germans had still not decided whether to move north towards the Channel or south to attack the greater part of the French army that was still intact. On the same day, the BEF launched their one large offensive of this campaign, the battle at Arras. It was a limited success for the British, but it made the Germans believe that a counter-attack was being planned.

The following day, the 22nd of May, the German Panzers began their move north; on the outskirts of Boulogne they met fierce resistance, and it took three days for the Germans to force a surrender of the garrison at Boulogne. At the same time, the BEF had retreated from Belgium and were behind the defensive lines east of Lille, some 40 miles from Dunkirk. As the Germans had lost half of their tank division since the start of the campaign, they were ordered to halt and blockade the BEF garrison at Calais.

The next day the situation was exceedingly grim for the Allied forces. The Belgian army was close to being completely decimated, thus exposing the BEF’s eastern flank. As well, at the coast, the Germans were blockading Calais, only twenty miles from Dunkirk, which was the last port available to the retreating BEF.

Hitler visited the German Panzers on the 24th of May, and after discussing the situation with General Rundstedt, he issued a command that the panzers were to halt at their current position and move no further. This allowed the German infantry and the Luftwaffe to attack the BEF, which was cut off to the north. At daybreak on the 25th of May, Lord Gort had orders to move north to support the French, but he could see that this was an exercise in futility so that evening, of his own accord, he ordered two divisions to move north from Arras to try and support the Belgian Army.

They were to reinforce II Corps, which was already holding that position and was tasked with protecting the northern flank of the BEF’s passage to the sea. On the same day, Churchill made the decision not to evacuate the garrison at Calais, but to spend the time reinforcing the western defenses of the beachhead at Dunkirk.

On the 26th of May both the French and the British decided to form a defensive ring around Dunkirk, but for very different reasons. The British were intending to retreat from the port while the French wanted to fight on. Also on the 26th, the Germans noticed the activity around Dunkirk and recognized what was happening.

Hitler allowed the tanks to move forward to within firing range of Dunkirk, and the brave men of the Calais garrison finally conceded defeat, having successfully held up the Germans for those crucial few days.

The 27th of May dawned, and the evacuation of the British forces started, but it was difficult. The German tanks had arrived, and the town suffered barrage after barrage of artillery shells. But the tanks could not penetrate to the harbor as the British had flooded large areas of low-lying ground around the port, effectively halting the tanks in their tracks. The BEF were still in grave danger – they still had the remnants of I and II Corps making their way down from the northern defenses, thus still outside of the Dunkirk perimeter. On the same day, the Belgian Army surrendered to the Germans.

The following day, the 28th of May, Lord Gort faced one crisis after another. He was formally advised of the surrender of the Belgian Army, and though this was not a complete surprise, it did leave his left flank dangerously exposed; it took fierce resistance from the BEF to stop the Germans from reaching the beaches. By that evening, most of the BEF were safely inside the perimeter, but by then the French commander, General Blanchard, had discovered that the British were leaving, and he was absolutely livid, refusing to fall back in line with the BEF.

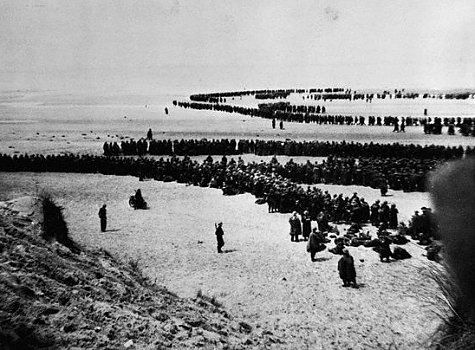

Eventually, by May 29th, most of the French army had fallen back to Dunkirk along with four British divisions, but the Germans had cut off the French V Corps, all of whom were captured. This ended the land-side war; now attention turned to trying to get over 300,000 troops collected from Dunkirk and returned safely to England.

On the evening of Sunday, May 26th, a number of passenger ships manned by Merchant Navy crews made for Dunkirk to collect the first of the troops being evacuated. These ships, along with all the others, had to avoid sandbars just off the coast, forcing them to run along the coast before turning toward England. The Admiralty was concerned that this run along the coast would expose these undefended vessels to German fire, so it ordered a path to be cleared through the sea minefields to create a shorter route of 55 miles, which limited exposure as much as possible.

At this stage, Captain Tennant, a Senior Naval Officer in Dunkirk, took charge of the shore embarkation parties. The Royal Navy intended to evacuate soldiers from the beaches, as the inner harbor at Dunkirk had been destroyed. The outer harbor was protected by two long concrete arms that were not designed to dock ships, but Captain Tennant instructed one destroyer to try docking against the arm. This was successful; the destroyers would take almost 8,000 men out over the next two days by this method. After that, Tennant, fearing Luftwaffe strikes, closed this embarkation point and directed everyone to the beaches.

The 28th of May dawned with evacuation moving at a rapid pace from the beaches. Tennant reopened the harbor, and six destroyers collected men from the concrete arms, but this day also saw the sinking of the ferry Queen of the Channel. After this, all ferries and personnel ships were not used during daylight hours – these ships, which were very large and extremely valuable to the evacuation effort, were restricted to working only at night. This day also saw the emergence of the Dutch ‘schuyts’ beginning continuous operations, eventually evacuating nearly 23,000 men.

By the 29th of May practice was making perfect as three times more men were rescued on this day. But the German Army had also gotten its act together, and it was a day of heavy Allied losses. A fast attack craft, the so-called E-Boat, sank the HMS Wakeful, a submarine, the U-62, sank the HMS Grafton, and a magnetic mine dispatched the personnel ship Mona’s Queen. A destroyer and six merchant ships were sunk by bombing in Dunkirk harbor.

The next day, the 30th of May, evacuation picked up from the beaches, but the loss of the destroyers the previous day encouraged the Admiralty to withdraw all modern destroyers from the evacuation effort. Because of the size of the operations at Dunkirk, Rear-Admiral Wake-Walker arrived to oversee the operation; when he realized that he had only fifteen old destroyers at his disposal, he convinced the powers that be to return seven new vessels to assist with the evacuation. Nearly 1,000 men were evacuated from the beaches, hidden by thick black smoke from burning oil, as well as a (fortunately) very low cloud base. This day the little ships were busy running back and forth to ferry men from the beaches to the larger vessels standing offshore.

The 31st of May was a difficult day for the British. The wind was blowing and it dispersed the smoke intended to protect the beaches. The bombing and artillery bombardment of the beaches reached a frenzied level. Large parts of the day found the beaches and harbor unusable, but despite this, 68,000 men were safely rescued. It also saw the rescue of Lord Gort, as the British were determined that he would not fall into German hands – a potential propaganda coup for the Germans. General Alexander assumed command of the troops at Dunkirk, and he ordered the abandonment of the eastern most beach, La Panne.

Sunday June 1st saw the men successfully being taken off at the harbor, but it also saw four destroyers sunk by the Germans. By breakfast on the 2nd of June it was estimated that 6,000 men from the British I Corps and 65,000 French troops guarding the perimeter were still on land at Dunkirk.

A final push was planned for the evening of June 2nd, and at 5:00 pm the Allied flotilla started moving across the Channel. By midnight the last of the British troops had been evacuated.

On Monday June 3rd a final effort was made to rescue the 30,00 to 40,000 French troops still left at Dunkirk, and at 10:15 pm, the destroyer HMS Whitshed led a flotilla of fifty ships to accomplish this. At 3:40 am on the morning of the 4th of June, the destroyer HMS Shikari, carrying 383 men, was the last vessel to leave Dunkirk. On that night a total of 26,000 French soldiers were rescued, 10,000 in little ships and the rest in destroyers.

With the departure of the Shikari, the fleet of little ships was dispersed and at 10:30 am on the 4th of June, 1940 Operation Dynamo was officially ended.

One of the enduring images of this evacuation was the use of the “little ships”. From the 30th of May to the end of the operation, hundreds of privately owned little boats made their way from England to France to help. While Admiralty figures suggest that they did not land that many men in England, their contribution in running men from the beaches to the destroyers anchored off shore cannot be underestimated. Thousands of men started their rescue by taking a short trip in a little boat, and this critically important role made a significant contribution to the ultimate success of the operation. Some two hundred of these brave little boats were lost during the operation.

The BEF suffered very heavy losses at Dunkirk and, while the rescue of 338,000 men is a magnificent effort, the BEF had 68,000 men killed, injured or missing. They also lost a significant amount of arms, ammunition, and other stores, which they could ill afford to do at the beginning of the war. The RAF lost 106 aircraft and, according to German sources, 80,000 men were captured. At sea, a total of 243 ships were sunk, including six destroyers, and another nineteen suffered damage. All in all a heavy toll indeed.

While Operation Dynamo saved the professional core of the British Army, they could not claim a victory. As Churchill said in a speech to parliament on the 4th of June, 1940, “We must be very careful not to assign to this deliverance the attributes of a victory. Wars are not won by evacuations.” The presence of all these troops in southern England certainly put paid to German intentions to invade England.

Churchill ended his speech with this very famous passage, which would not have been possible without the recent events at Dunkirk:

“Even though large tracts of Europe and many old and famous States have fallen or may fall into the grip of the Gestapo and all the odious apparatus of Nazi rule, we shall not flag or fail. We shall go on to the end. We shall fight in France, we shall fight in the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air; we shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be.

We shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender; and even if, which I do not for a moment believe, this Island or a large part of it were subjugated and starving, then our Empire beyond the seas, armed and guarded by the British Fleet, would carry on the struggle, until, in God’s good time, the New World, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and the liberation of the Old.”

As for the proposed movie, the use of this large-format film is appropriate for encompassing the drama that was Operation Dynamo. It is easy to imagine the wide screen swept with images of hundreds of small boats ferrying troops out from a smoke-blanketed beach to a destroyer looming out of the murk.

Luftwaffe pilots battle with RAF squadrons and on the ground, the perimeter of Dunkirk is fiercely protected by the BEF alongside the French. Christopher Nolan is such an experienced director that we can be certain that he will produce a film that captures the bravery of both sides at the commencement of a bloody war that decimated most of Europe.