German prisoners believed they were living in luxury the way the British officers were treating them. The prisoners were held in large, well-kept homes where they were even allowed personal servants, wine, and food. It was as though being prisoners proved to be a higher luxury than elsewhere. However, what the prisoners did not know is that the homes and servants were all a ploy. The British had special tactics in mind for the German officers.

The prisoners were held in three separate locations – Latimer House in Amersham, Wilton Park in Beaconsfield, and Trent Park in north London. The first two housed held U-Boat submarine crews and Luftwaffe pilots. The officers were held at the houses for two weeks and then eventually were moved to captivity elsewhere.

While being held captive, the Germans would comment about how stupid the British were to afford their prisoners such luxury; one man even wrote to his family that he wished they were there to enjoy the lifestyle. What the Germans did not know was that the entire house they were held captive in was bugged from floor to ceiling, inside and out. From the Germans’ conversations, British intelligence was learning the Germans’ topmost secrets.

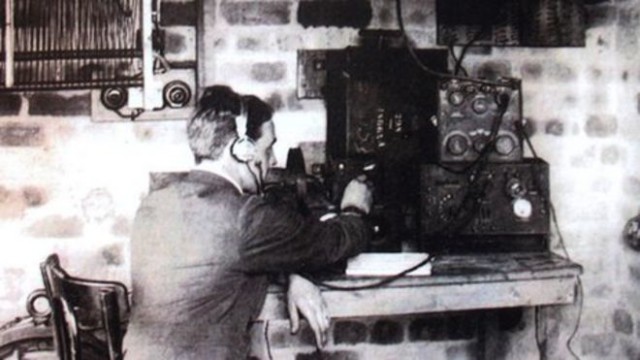

British intelligence hired Germans of Jewish origin, who had successfully fled from the Nazis, to man listening stations in the homes where the German’s were allowed to congregate. In each of the three homes there was a secret room dubbed the “M” room. The “M” stood for microphoned and there were secret listening devices on constant watch in those rooms.

Over the course of the war, there were 59 generals held captive. One author who wrote a book on the operation, Helen Frey, says that the amount of information the British got from this eavesdropping proved to be vital for the war. The operation was so successful that it consistently got funding from the government in order to continue. Frey even believes that the eavesdropping was just as important as breaking the codes at Bletchley Park, and that without the eavesdropping it might have been possible that the Allies would not have won the war.

There were over 100,000 transcripts written from the eavesdropping. The most important and vital information was that of the conversations about the military capability, weaponry, and the newest technology. One particular conversation to be listened in on concerned a German V2 rocket site. The allies were able to locate it, bomb it, and prevent the Germans from using the rockets on Britain.

Along with the war information, the prisoners were actual proof that the army knew and were part of the mass killings of the Jews. Their admittance gave proof that they were guilty of war crimes. Frey says that the German army had denied those accusations, and it was actually believed for 65 years that the Germans had nothing to do with the mass killings. These British transcripts proved that rumor wrong.

The German prisoners felt so comfortable at the homes that they had a garden party which was hosted by Colonel Thomas Kendrick, the man who secretly oversaw the bugging operations. At the party, the Germans relaxed and enjoyed themselves enough that they spilled even more secrets. Frey said that the reason the generals were giving so much information was because they believed they were entitled to special treatment according to their status.

Winston Churchill was rather irate at the fact that the generals were being pampered. He demanded that the program of housing German war prisoners in luxurious homes be stopped. However, that would have resulted in the bugging process being stopped as well; considering the amount of information gleaned from the program, British intelligence continued with the bugging operation and merely stopped telling Churchill about it.

It is believed that of the 100 secret listeners that worked in the “M” rooms there are only two alive today. One of them, Fritz Lustig, is 93 years old and lives in Muswell Hill, London. Lustig was actually born in Berlin and baptized as a Protestant. However, he had several Jewish family members and thought it would be safer to leave the area in April of 1939. He made it to England where he would be quite useful. He ended up joining the British army’s Royal Pioneer Corps. He not only spoke German, but he also spoke English, which helped him get into the intelligence corp.

Lustig doesn’t remember anything he wrote down in his transcripts, except for the word “atrocity” in bright red pen. He said it didn’t bother him to listen to the conversations because none of the listeners were emotionally attached to the German regime. It’s possible that the information the listeners gleaned from bugging those houses proved to be the turning point for the war.