A memoir from a New York Man Who Grew Up a Jewish Refugee in World War II Japan and Worked with the US Military as an Interpreter and Guide at Age 14

Isaac Shapiro was born in 1931 in Japan, the son of Russian Jewish refugees who left Russia for differing reasons (his mother, fleeing pogroms; his father, escaping the Revolution.) His parents married in Berlin and then traveled to Paris, Palestine, Harbin, China, and finally Japan, in search of security for their growing family and work as classical musicians.

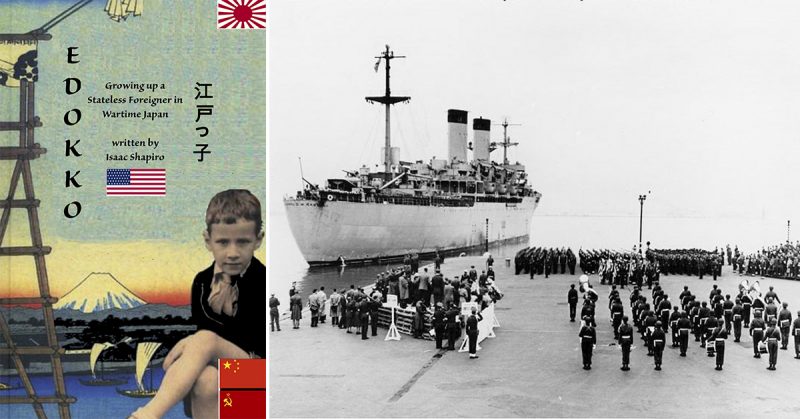

Shapiro’s memoir, Edokko: Growing Up a Stateless Foreigner in Wartime Japan, has just been reissued (Amazon).

The book details the struggles of the Shapiro family to find sanctuary as rising anti-Semitism sweeps Europe in the late 1920s. Shapiro is born in Japan but spends his first five years in the Jewish refugee community of Harbin, China, before returning to Japan in 1936. The family live as ‘stateless foreigners’ throughout the war, as their host country allies itself with Nazi Germany.

Relocated by the Japanese government to Tokyo when the war’s end looms, they survive devastating bombings by the US military.

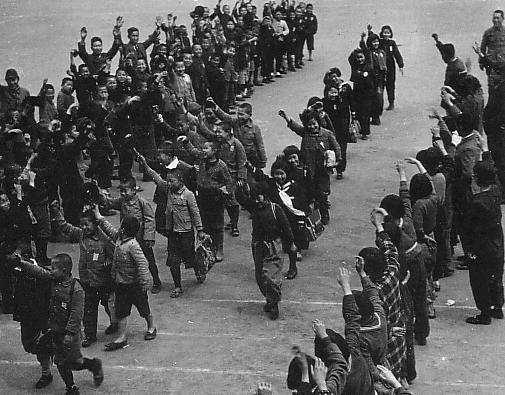

When the war ends in 1945, 14-year-old Ike travels to Yokohama Harbor to watch U.S. troops come ashore. Military leaders were startled to see this young Caucasian boy standing in the harbor. They asked what he was doing there, and then invited the 14-year-old, who’d studied English in school, to work with them as an interpreter and guide.

Within a week, Ike is touring Hiroshima with the US military and forging friendships with its leaders — including a childless Marine Colonel from Arkansas who, with his wife, invites Ike to move to the U.S. with them.

Thanks to their sponsorship and support, Ike, a stateless refugee, becomes a U.S. citizen, serves in Korea, attends Columbia and embarks on a very successful legal career in Manhattan. (Most of Ike’s family follows him to America where they too find success.)

Ike’s story is fresh and unusual, illuminates a nearly unknown part of the Jewish experience of the 1930s and 40s, and presents a rare view of World War II.

Excerpt from the book

14-year-old Isaac is Recruited to Work with the U.S. Military

….We’d read in the newspapers that General MacArthur was temporarily headquartered at the New Grand, having landed in Japan the day before, on August 30. It was only in mid-September that MacArthur set up his permanent headquarters in the now-famous Daichi Life building in Tokyo.

The New Grand was an important choice as the Allied military headquarters. It was the only classic western hotel in Yokohama and it had the best view of the harbor. Yokohama’s leading businessmen had built it in late 1927 as a symbol of the city’s rebirth following the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. Mama and her friends had often taken us to the New Grand for tea or ice cream, and it felt strange to see it transformed into a military headquarters, with American soldiers and jeeps guarding the entrance.

Standing at the water’s edge dressed in my dark shorts and my navy-blue long-sleeved sweater, I looked out at the busy harbor. I’d stood on that very spot with my best friend, Holt Meyer, six years earlier, watching the American cruiser, USS Astoria, pull in, carrying a Japanese ambassador’s ashes, on a peaceful diplomatic visit. Now, there were more American warships crowding the harbor than the eye could count.

I watched the Americans come ashore, hundreds of them crammed into motorboats, speeding from their ships to the docks. Nothing about that moment was familiar or ordinary. It was unreal and I could feel the excitement. I watched one motorboat zoom toward the dock and soon I could make out the GIs ‘ faces. A few of the American soldiers seemed to be staring right at me. I stared back.

Suddenly, I was startled by a voice, much closer and quite loud. “Hi, there!” I turned quickly. A tall U.S. Army officer, in his late twenties, had joined me on the embankment. “I’m Captain Kelly,” he said with a broad smile and held out his hand. I took it and waited for him to continue. “Do you speak Japanese?” he asked. “Yes, sir,” I replied. “Good! Then you can help me. I’ve commandeered a school bus but I can’t communicate with the driver. Come with me and tell him where to go.”

Reproduced with permission by seasidepress.org