Elite units of the ancient world usually gain their elite status by being wealthy enough to afford the best arms and armor, such as cataphracts of the eastern powers, thus allowing them to have the highest impact in a battle. For the Iberian light infantry armed with the lethal falcata, elite status was born out of sheer talent on the battlefield. The second Punic War gave Iberian warriors a stage to show their prowess and the agonizingly difficult conquest of Spain by the Romans showed how well these men could hold their ground.

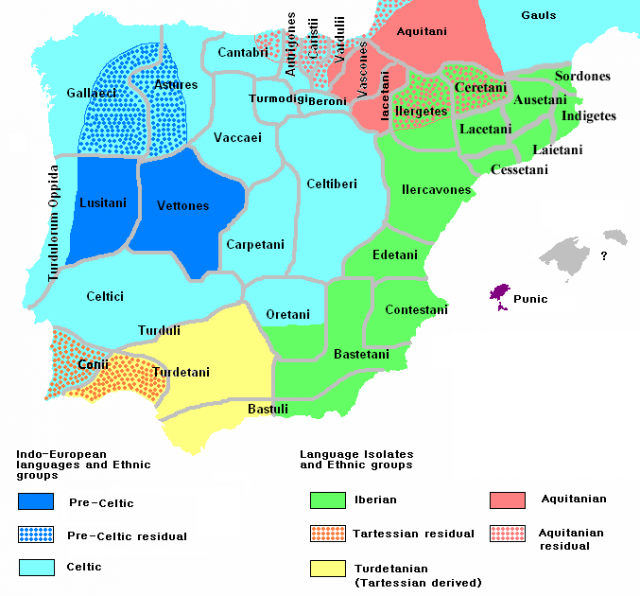

Like the Celts and Gauls, the Iberians were a fragmented tribal people. Northern and central Iberia were home to Celt-Iberians who held their own identity and were known as the most aggressive of any Iberian regions. southern and eastern Iberia are where the full Iberian tribes were found. These tribes had the advantage of plentiful resources to make high quality arms and armor. The falcata was one of the highest quality blades of the Mediterranean when made by expert Iberian smiths. To test the quality a soldier would place the blade flat on his head and pull down on the tip of the blade and the end of the handle until they touched his shoulders. Upon letting go the sword sprung back to its original shape with no hint of a bend.

The falcata was shaped with a straight single edge for the first half or so of the blade before bending slightly, widening and gaining a double edge which led to a sharp point. The blade was thinner in the middle with a bulge near the tip which gave the blade good weight and momentum for swinging blows while still allowing for quick thrusts. The hilt was made with the same piece of metal as the blade and almost always wrapped around to form a handguard. The quality of the sword combined with the design allowed it to function as a light sword, but with the power to cut through shields or shatter inferior weapons. It was especially adept at lopping off spear points as the widest part of the blade acted as a hatchet.

The Iberians had heavy infantry who wore a vest of mail, greaves and a large shield similar to a Roman’s scutum, but these heavily armored troops were not the most impressive of the Iberians. The lighter infantry wore just a short tunic with a wide leather belt and often no armor at all, but occasionally a bronze cap. They carried the falcata and a small buckler style shield called a caetra.

Being so unburdened the Iberians were known to fight so elegantly that it was referred to as “acrobatic”. In battle the Iberians would throw a thin javelin of solid metal which could pierce through shields and men, then they would close in on the enemy and fight as individuals. Using combinations of quick thrusts, slicing counters or bashing overhand strikes, the Iberians overwhelmed their opponents. Because of their skill in battle these very lightly armed men were often counted as heavy infantry and Hannibal used them, along with other heavily armored Celts, to anchor the center of his line at Cannae against 80,000 Romans.

The Iberians were also known for their skill in horse breeding and riding. Though they weren’t as naturally skilled as the Numidians, their use of the lance and the falcata on horseback allowed them to serve as heavy infantry as the falcata was more than able to pierce or crush through most armored cavalrymen at the time.

Iberians served with distinction through the Punic Wars though each tribe had different loyalties. They anchored Hannibal’s Italian infantry. When the deserted the elder Scipio brothers during their Iberian campaign against Carthage, it depleted the Roman’s so much that the brothers’ army was destroyed and they were killed. When the younger Scipio, soon to be Africanus, took over the Iberian campaign he secured the loyalty of many Iberian tribes. He was so impressed by the falcata that he had Iberian smiths teach his smiths how to make the blades and equipped his entire army with a version known as the gladius hispanicus. It is unclear if Scipio completely copied the falcata or if he tweaked the design to head towards the later Roman gladius. Regardless, Scipio’s troops had a huge degree of success when they invaded Africa in 204 and were able to beat Hannibal’s troops head on at the battle of Zama.

After the second Punic War the Romans viewed Iberia as theirs and sought to occupy parts of it. This was hardly accepted by the bulk of the tribes and fierce wars ensued. As the peninsula was comprised of multiple independent tribes, the conquest was broken up into several separate wars. The fighting in Iberia was incredibly fierce; women often took up the sword and fought alongside men, and many times talks of peace led to open betrayals. When faced with certain death the Iberian warriors took a poison which after killing them, contorted the muscles of their face to form a sinister smile; needless to say this caused quite a lot of disquiet among the Romans.

During the wars the Iberians often employed guerrilla warfare, waiting for Roman supply lines or a foraging party to become vulnerable before attacking. Due to their superior one-on-one fighting skills these ambushes were often huge success for the Iberians. The Numantine tribe in central Iberia would put up the fiercest fights with a series of six different generals failing to subdue the mighty city of Numantia. Finally the Romans sent Scipio Aemilianus Africanus, the adopted grandson of the original Scipio Africanus. Aemilianus gained fame through the destruction of Carthage to end the Punic Wars and once in Iberia he set to work. By building several forts around Numantia he limited opportunities for Iberians to ambush his men while keeping the Numantines bottled up until they pled for peace, though most ultimately committed suicide.

The capture of Numantia subdued the region until the reign of Sulla when they again rebelled and employed guerrilla tactics to great effect. A young Pompey gained a great deal of experience fighting in Spain and the campaigns would prove to be his most challenging before his war with Caesar. The Iberians were a strong and fierce people who wielded a most impressive weapon with unmatched skill, leading them to have an impact greater than the heaviest of infantry. Their allegiances drove the successes and failures of the second Punic War and they defiantly fought for their independence for several centuries before succumbing to the power of Rome.

By William McLaughlin for War History Online