THE LOSS OF THE EMPIRE WAVE

Suzanne Make recounts the loss of a British merchant ship in 1941 that saw a harrowing ordeal for the crewmembers that were able to get into a lifeboat.

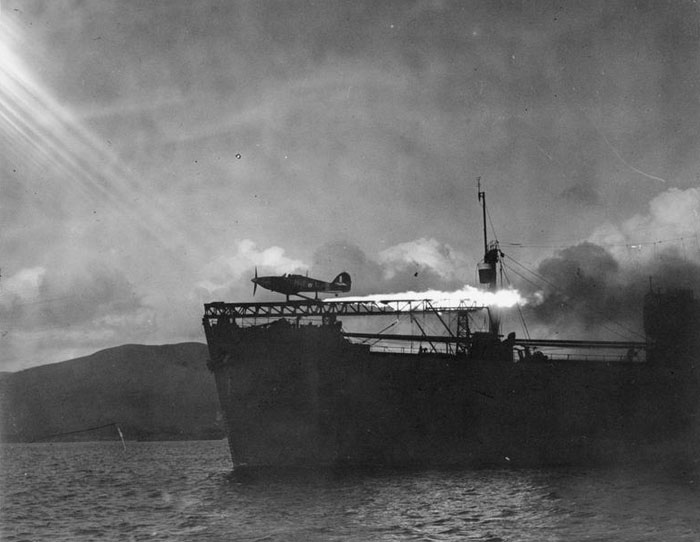

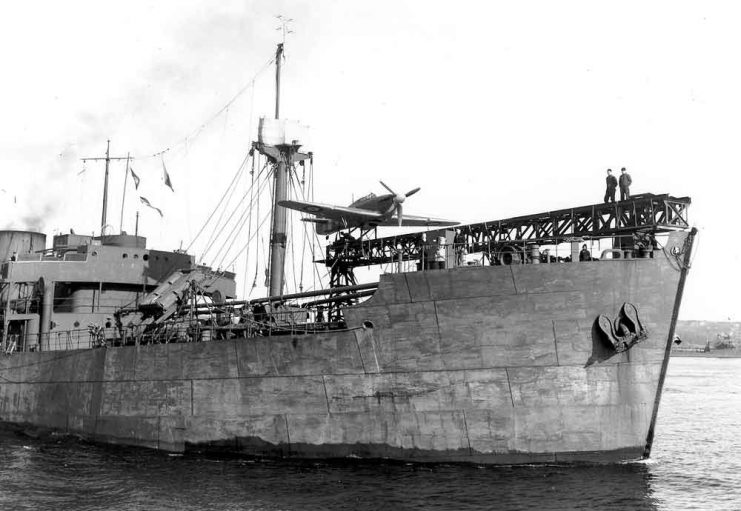

In the early hours of the morning of the 2nd of October 1941 the unescorted CAM (Catapult aircraft merchant) ship the Empire Wave was torpedoed by the German U-boat U-562 about 500 miles east of Cape Farewell, Greenland. She had left Sunderland on the northeast coast of England and was heading for Halifax, Nova Scotia in a convoy but had straggled behind due to engine trouble. The ship sank fast taking over half of her sixty strong crew with her.

Twenty-seven men managed to scramble into a lifeboat. When the ship was hit, many of the crew had been asleep and were wearing only thin vests so by the time they were in the lifeboat they were soaked through and freezing cold in gale force winds and stormy seas in the middle of the North Atlantic Ocean.

Guided by the stars and on tiny rations, they needed to make their way to Iceland, over five hundred miles away.

Chief Officer John Cameron managed to keep a diary and logged his thoughts about the terrible conditions in the lifeboat and the awful situation that the sailors found themselves in. He wrote about how wet and cold they all were and how they constantly had to bail the icy water out of the boat.

After five days he wrote that the men were complaining of numbness in their feet. They massaged each other’s feet to try to help circulation, but by the sixth day their feet had started to swell with massage bringing little relief. On the eighth day their feet had started to turn grey.

By day nine all the men’s feet were swollen and turning black. One man’s toenails were dropping off and he was hallucinating. Some had painful feet while others had no feeling at all. On the eleventh day the crew were all so weak they were unable to bail, meanwhile the compass light failed and because of the cloud they had no stars to navigate by.

On the twelfth day one of the crew, Donald McPhee, died of exposure. The others were simply too weak even to lift their own arms, so they could not bury him at sea. On day fourteen, John Cameron wrote that it was extremely cold and nothing could stop the men from shivering. All of the were suffering from severe frostbite and exposure, as well as hunger and thirst.

On the fifteenth day 16th October 1941, an Icelandic fishing trawler, the Surprise, rescued the men. By this time all them were desperately ill, many were so sick and drifting in and out of consciousness that they didn’t even realise they’d been rescued. They were taken to St Patrick’s Fjord before being transferred to hospital in Reykjavík.

Thomas Dixon was a deck boy on the Empire Wave. His father John had perished when the ship went down but young Thomas survived fourteen days at sea only to die at the hospital in Reykjavik two days after being rescued. He would have been cold and frightened having lost his father in the explosion.

At fifteen years of age, Thomas was just a child.

RAF Aircraftman 1st Class William Morton Boal was also rescued but died from exposure five days later. The Empire Wave carried a Hawker Sea Hurricane Mk Ia fighter for air defence that could be launched from the ship using a rocket-assisted catapult. This explains why airmen were on board.

Able Seaman Donald Macphee came from Isle Ornsay on the Isle of Skye. He was fifty-two when he died on the lifeboat two days before the rescue. Donald had already been shipwrecked twice in 1941 on the same day.

The first time was on board the Norman Monarch that was torpedoed on 20th May 1941 and then on the rescue ship Harpagus later that day. Many men were killed on both these ships but the report by the Chief Officer of the Norman Monarch mentions Macphee, stating that if it hadn’t been for him there would have been no survivors at all and that “with great presence of mind as the ship was sinking he managed to free the lifeboat and save many men.” He stands a symbol of a man who knew his duty in a time of crisis keeping up the spirits of the younger lads.

Having survived three sinkings in six months and saving many lives, Donald died from exposure to the elements in the lifeboat. He had been awarded the Lloyd’s War Medal for Bravery and the King’s Commendation in August 1941.

John Cameron survived being torpedoed on two further occasions. Of the loss of the Empire Wave, the citation for the award of the MBE was quoted in the London Gazette published on 3rd of February 1942 “It was due to his masterly seamanship and his courage that so many were brought to safety. Cameron was also was awarded the Lloyd’s War Medal for his actions and received the OBE in 1945.

Jim Adie was a sixteen-year old cabin boy aboard the Empire Wave. He wrote after the rescue that the cramped conditions in the overcrowded lifeboat were almost unbearable. The icy sea drenched them and their clothes were frozen solid at night. His ankles swelled to twice their normal size. He remembered praying but had lost consciousness when he was rescued and tenderly hoisted onto the fishing trawler. He lost several toes but was later able to return to work in heavy industry and lead a relatively normal life.

Every single man on the lifeboat suffered severe frostbite and had to have toes or limbs amputated. At least one man had to have both his legs removed.

The men had their pay stopped when the ship was sunk. Their families were not informed about the sinking until after the rescue. They did not receive a war pension or get any help from the British Legion. As merchant seamen they all carried on with their lives coping with their disabilities as best they could. There is nothing on Iceland to commemorate these brave men. No brass plaque in the tiny village of Patreksfjordur in the Westfjords to show where those wretched souls came to land.

Donald Macphee, William Morton Boal and young Thomas Dixon lie side by side in the beautifully kept cemetery at Fossvogur near Reykjavik. It was difficult to push the little wooden crosses that I had brought along into the frozen icy ground when I visited the cemetery on a recent visit to this lovely island. But you will understand how, having read about these courageous men I had to visit Fossvogur and pay my respects to them.

I would like to thank Stan Adie and Seymour Hosking for their kind help in providing information on their family members.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Suzanne Make, Military history enthusiast, explorer, adventurer, taphophile, amateur photographer. And you can follow Suzanne’s Facebook page here My Western Front Photographs