A US war journalist, Ernie Pyle, made a name writing scores of columns about the life and times of frontline soldiers. His storytelling methods touched millions, because he wrote his columns in the form of letters written by weary soldiers to their families back home.

A professor emeritus at Indiana University, Owen Johnson, said that it is not possible to tell which of the columns Pyle produced during the war was his favourite. Johnson was speaking at a ceremony, which was held at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu. Ernie Pyle, along with 3400 others, is buried in this cemetery.

Johnson, who is also regarded as a ‘Pyle scholar’, said that Pyle did not think about favouring one of his works over others. Pyle did what he did, out of his passion and love. The ceremony was held to dedicate a plaque and stone to the gallant infantrymen and those who wrote about their lives in the battlefields. According to Johnson, Pyle’s favourite columns must be the ones that were left unfinished at the end of his life.

His last column was about the days and nights at the Battle of Okinawa. He wrote about the fierceness of the battle and resilience of the men. His tone is one of numbness and extreme fatigue as the battle takes its toll on those involved. But Pyle did not have enough time to see the end of the battle; he was killed with a shot to the head on 18th April 1945. His column about the Battle of Okinawa remained unfinished.

Pyle’s accounts of the battle were emotional and yet cold at the same time. He felt a strong connection with those lying dead in the ditches; however, he did mention that ‘joyousness of high spirits’ demands that one must continue to march. He said that it is not realistic to expect those who survive from this hell to forget what they had seen. The images and the emotions attached to them get embedded in the memory forever. Pyle writes that, amid the chaos, the piles of dead men become such a monotonous phenomenon that over time you lose your emotions and start hating it all.

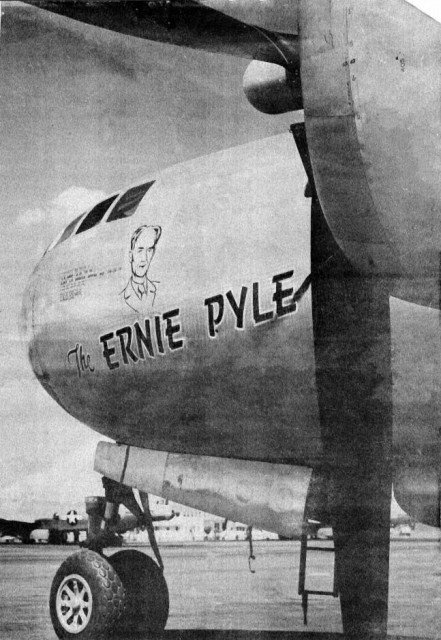

Pyle followed the lives of the infantrymen for 3 years, from the hot fronts of Africa to Italy, France and then the Pacific. He was respected and loved by soldiers, because his portrayal of the war was as close to reality as possible. He did not just report the events, he lived the moments, felt what soldiers felt, saw what soldiers saw and eventually died how soldiers die.

Pyle was already a famous reporter even before the war, and earned the name ‘the old man’ from soldiers in North Africa in 1942. He never carried a notebook or journal with him; he experienced the war and then wrote about it later from his memory and emotions. He wanted to join the military during the First World War, but his parents insisted that he should carry on his education. In the 1920’s, he started making his name as an expert writer on aviation. He wrote about the struggle of ordinary Americans during the Great Depression, where he honed his storytelling skills.

Congress passed a bill, ‘The Ernie Pyle Bill’, granting extra pay for those fighting frontline battles. This was made possible as a result of Pyle’s rigorous writing about how infantrymen risk more than those who aren’t fighting at the front.