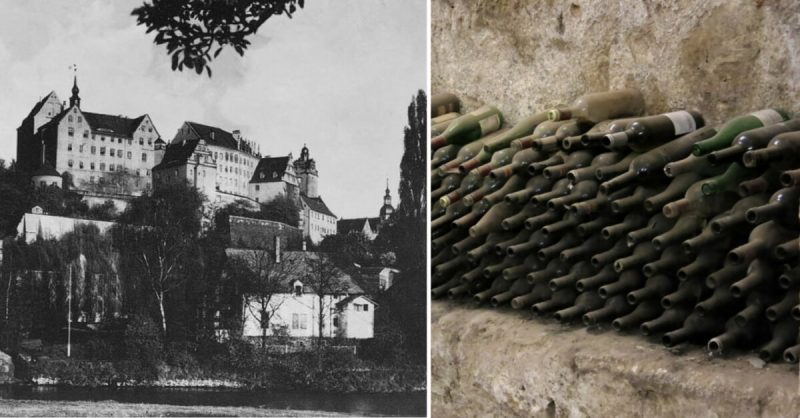

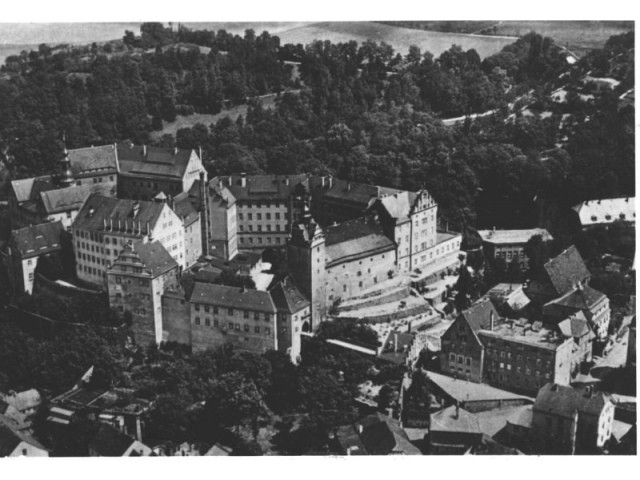

Colditz Castle is situated on a rocky outcrop some thirty miles from Leipzig in Germany. Originally built in 1200 AD, the castle was subsequently altered and rebuilt several times. During the 19th century it was used as a hospital and sanatorium, and in 1933 when the Nazi party came to power the castle was turned into a political prison. In 1939, at the outbreak of the Second World War, Colditz castle became a prison for captured allied troops.

Field Marshall Hermann Goering, head of the Luftwaffe and founder of the Gestapo, was later to proclaim that the castle was escape-proof. That remark was sufficient to ensure that many of the men who were imprisoned there would see it as their duty to escape if at all possible.

There were dozens of escape attempts, and thirty-three prisoners made it to freedom. The rest were either detected as they made their attempt, or were recaptured shortly afterwards.

One of the most famous internees was Douglas Bader, a British fighter ace who, despite the earlier loss of both legs, flew a Spitfire in the Battle of Britain. Shot down over Germany, Bader was sent to several prison camps and made three unsuccessful escape attempts. He vowed to be “a plain, bloody nuisance to the Germans”, and in August 1942 he was sent to Colditz, which by this time was used solely for prisoners who were hardened escapees. Bader remained at Colditz, making a nuisance of himself until the castle was liberated in 1945.

British Royal Artillery Officer Airey Neave was sent to Colditz in May of 1941. Neave and a fellow officer had been captured by the Gestapo following an escape from Stalag XX-A, near Thorn in German-occupied western Poland. In January, 1942, Neave and a Dutch officer escaped, wearing fake German uniforms. The pair made it to the Swiss border and freedom. Neave was the first British officer to successfully escape from Colditz. He was later awarded the Military Cross and Distinguished Service Order. After the war, Neave became a Conservative Party politician. He was murdered in March 1979 when the Irish National Liberation Army planted a bomb in his car, the New District reports.

There is a story that during a tunnelling operation, Neave and a group of fellow prisoners mistakenly ended up in the Colditz castle Commander’s wine cellar. They are reputed to have consumed over 100 bottles of wine, refilling them with urine. The story contains factual errors, and there is no evidence to support the account, although some French officers did escape via the cellar.

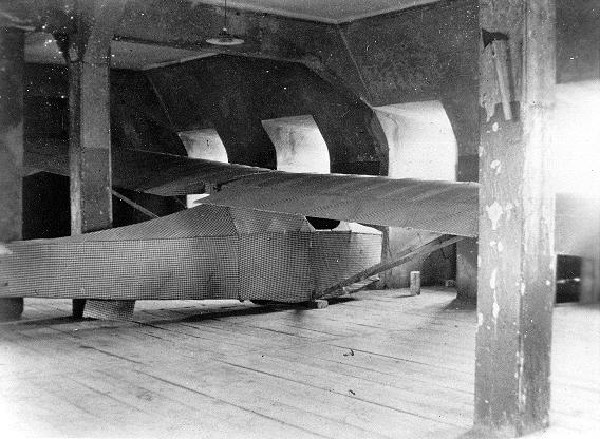

One lavish scheme even included a glider, the “Colditz Cock”, that was kept in a remote portion of the castle’s attic, completed in the winter of 1944–45, but following the Great Escape, in which 50 escapees were executed, all further escape attempts were officially discouraged and the glider was never used. When the camp was liberated by the Americans in late April, 1945 the glider was brought down from the hidden workshop to the attic below and assembled for the prisoners to see. It was at this time that the only known photograph of the glider was taken. For some time after the war the glider was regarded as either a myth or tall story, as there was no solid proof that the glider had existed and Colditz was then in the Soviet Occupation Zone. Bill Goldfinch, however, took home the drawings he had made when designing the glider and, when the single photograph finally surfaced, the story was taken seriously.

In 1999 a full-sized replica of the Colditz Cock was commissioned by Channel 4 Television in the UK and was built by Southdown aviation Ltd. at Lasham Airfield, closely following Goldfinch’s drawings. It was test flown at RAF Odiham in 2000, with several of the ex-prisoners of war who worked on the original watching. The escape plan could have worked.

In April 1945, U.S. troops entered Colditz town and, after a two-day fight, captured the castle on 16 April. In May 1945, the Soviet occupation of Colditz began. According to the agreement at the Yalta Conference it became a part of East Germany. The Soviets turned Colditz Castle into a prison camp for local burglars and non-communists. Later, the castle was a home for the aged and nursing home, as well as a hospital and psychiatric clinic. For many years after the war, forgotten hiding places and tunnels were found by repairmen, including a radio room set up by the British POWs, which was then “lost” again only to be re-discovered some ten years later.