Deep in the mountains of Bavaria is a concrete doorway set into the side of the mountain. Even in the height of summer, the thick steel door is cool to the touch, and drips with condensation. From the edges of the door frame comes a chilling cold breeze. It isn’t marked on any tourists guide maps, as the government would prefer that you had no idea that it exists.

Behind the steel door lies the underground secret bunker complex of Adolf Hitler.

This multi-roomed subterranean compound is composed of an apartment and a set of underground chambers for fellow Nazi inner circle members—over four miles of tunnels, bunkers and hidden rooms in total. Above ground, an entire village was built as an Alpine retreat for the Nazi government.

But with the war failing, the mysterious underground complex was to be the last redoubt of the Third Reich. Carpet bombed by the Royal Air Force in April of 1945, then locked up by the occupying U.S. Army, it was handed back over to Germany in 1952 with the proviso that the remnants be blown up again out of existence. But not everything was destroyed, and today, you can still visit the secret ruins of the Nazi’s planned Alpine fortress.

THE BEAUTIFUL BERCHTESGADEN

Berchtesgaden is one of the prettiest towns in all of Europe. Surrounded on all sides by the soaring Alps, the secluded picturesque town is marked by domed church steeples, terracotta tiled houses, wild flowers and beer gardens. The river in the center of town runs with water fed from the lake of the Konigssee. The unspoiled beauty of Berchtesgaden and its cheerful way of life has made it a beloved holiday destination for centuries of Germans.

Its most infamous tourist started coming here on holiday in the mid-1920s. Hitler stayed in a modest rental cabin overlooking the town that he wrote the second half of his autobiographical work, Mein Kampf. By the time of his appointment as Chancellor of Germany in 1933, Hitler had earned roughly 1.2 million Reichsmarks in royalties from his book (the average annual income of a teacher in 1933 was around 4,000 marks). With his newfound wealth (rumored to be supplemented with the annual royalties he received from appearing on postage stamps), Hitler began to build a mansion not far from his small cabin, in the mountain retreat of Obersalzberg, overlooking Berchtesgaden. Called the Berghof and completed in 1935, Hitler’s Alpine home was as imposing as it was luxurious, dominated with giant 25-foot picture window which looked onto the mountains of his native Austria.

The sweeping window was chosen deliberately by Hitler. Legend has it that Charlemagne, the ancient unifier of Western Europe slept in those mountains, awaiting the next leader to rule Germany. If Bismark’s second reich was relatively short lived, Hitler’s third, was supposed to take the mantle from Charlemagne and rule for a thousand years. Hitler spent around a third of his time in power at the Berghof, entertaining such luminaries as David Lloyd George, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Mussolini and Neville Chamberlain. It was from his plush mountain mansion that Hitler decided to annex Austria, invade Czechoslovakia, and set into motion the evil that would ultimately cost the lives of over 60 million people.

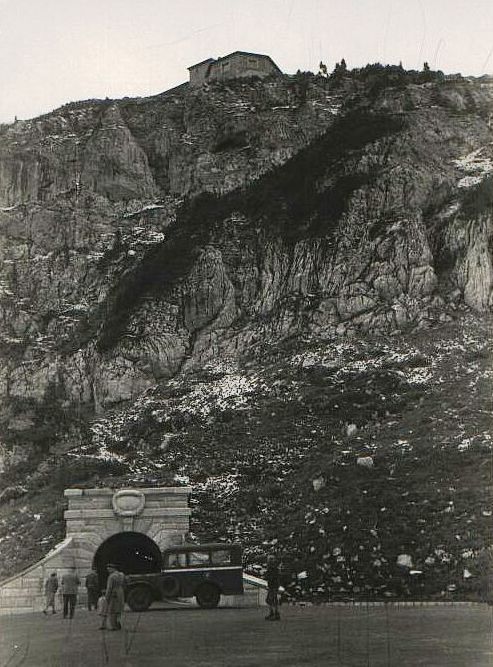

For his 50th birthday, an even more impressive house was built for Hitler, this time soaring 6,000 feet high on the Kehlsteinhaus, above the Berghof. Today it is known by its more infamous name, the Eagle’s Nest.

A remarkable feat of engineering, the Eagle’s Nest was reached by what is still Germany’s highest altitude road. At the end of the road, a tunnel was bored into the mountainside that ended in a solid brass elevator. The gleaming elevator (that still runs today) would have carried Hitler to hismountain top retreat.

Despite its magnificence, Hitler rarely set foot in his expensive birthday present; he was rumored to suffer from chronic claustrophobia and vertigo.

Today the Berghof and Eagle’s Nest remain well-known symbols of Hitler’s reign in power. What is less well known is that surrounding Hitler’s home, grew an entire village both above and below ground.

LIFE IN THE NAZI SUMMER HOMES

Beginning around 1936, the leading figures in the Nazi party began building similarly grandiose homes near Hitler. Martin Bormann, Hitler’s private secretary and head of the Party Chancellery, was in charge of the project, which entailed clearing Obersalzberg of the farms, inns and hotels that had catered to generations of holiday makers.

Soon, Goering, Himmler, Hess, and Goebbels also had opulent mansions A children’s asthma clinic, situated there to benefit from the clear mountain air, was occupied and turned into a house for Bormann himself. Obersalzberg became a village community for around 2,000 high ranking Nazis and their families. It featured a bowling alley, cider press, cinema, a model farm, kindergartens and outdoor swimming pools. They even kept bees. A workers camp for the highly paid Italian laborers, experts in mountain road building, was constructed. Hitler’s chief architect, Albert Speer kept a design studio in a valley that featured a giant luxury hotel on the overlooking ridge called the Platterhof.

By 1943, the Allied gains in North Africa and Italy made the threat of imminent air raids a distinct possibility, casting a shadow over the idyllic mountain retreat. Again orchestrated by Bormann, the Nazis started to burrow deep into the mountain for safety. All the principal Nazi mansions soon had matching subterranean apartments spreading out from their basements. Linked by a complicated 4-mile-long tunnel system, facilities for storm troops, secretaries, medical staff and families were established underground. These dwellings replicated the homes above them, complete with air ventilation systems, dehumidifiers and central heating. Goering’s bunkers contained his formidable collection of rare wines, champagnes, spirits and seized priceless art.

This was to be the Nazi’s Alpine fortress, a “national zone of retreat”, from where Hitler and his inner circle would conduct the grand finale, the “Gotterdammerung”— twilight of the gods.

Germany’s foes got wind of the complex thanks to aerial surveillance photography carried out between 1943 and 1945. Allies knew about the mansions and the British Secret Service had been formulating plans to assassinate Hitler. But the large scale underground earthworks being carried out at Obersalzberg remained mysterious. It is thought that the Allies suspected not a giant underground community, but that this was a new site for German arms manufacturing, especially of the feared atomic bomb. In April 1945, hundreds of Lancaster bombers from the Royal Air Force left Northern Italy to obliterate not only the mansions of Obersalzberg, but whatever was going on underground. The air raid missed the Eagle’s Nest but devastated the rest of Obersalzberg, destroying most of the buildings, including the Berghof. A testament to their formidable mountain defenses, though, is that of the 2,000 inhabitants taking refuge in the secret bunkers, only six died. Weeks later, the French and US Army took Berchtesgaden, what was left of the model Nazi village and the Eagle’s Nest.

The U.S. remained on the mountain until as recently as 1996. What survived from the air raid was re-appropriated; the giant luxury hotel became the hotel General Walker. Speer’s studio and home became private residences, as did some surviving SS barracks. The Eagle’s Nest became a restaurant and beer garden in the 1950s. Only open today in the summer months, due to the dangers of avalanches, it attracts up to 3,500 curious visitors daily.

But the vast underground complex was simply sealed off.

WHAT THE MUSEUMS DON’T TELL YOU

There is a delicate balance between the historic importance of such sites, and the overriding compulsion to wipe it from the face of the earth. Presumably this is what led the U.S. to insist that Germany dynamited surviving structures of Obersalzberg in 1952.

Museums and “Documentation Centres” were built at Obersalzberg and Nuremberg. At Obersalzberg, the museum, which all Munich school children are required to visit, along with a trip to Dachau, speaks unflinchingly of all the evils of Nazi Germany. The Documentation Centre also opened up a small stretch of the tunnels, which were originally built as a refuge underneath the hotel.

My contact in Berchtesgaden was one half of a husband and wife team that have been providing tours of the area since 1990. Christine Harper was born to a German mother and a father in the American Air Force. Her husband David’s aunt was the last wireless transmitter working in Paris for the French Resistance, and was ultimately killed by the Germans. Together they have been providing fascinating in depth tours that include not just the Eagle’s Nest, but the whole incredible secret history of Obersalzberg.

For decades, Harper says, “the problem in Germany was that education on World War II wasn’t mandatory, so they didn’t have to talk about it.” Times have changed, though. “The younger generation are allowed to be interested in the subject where before it was taboo,” she notes.

But while the museums are a definite step forward, large parts of the ruins of Obersalzberg are pointedly not mentioned; there are no sign posts for what hides in the woods.

Across the street from the old General Walker is a power station by the side of the road. Behind the concrete structure, about a minute’s uphill walk into the forest, are a small collection of stone foundations. This is all that remains of the original cabin where Hitler wrote the second half ofMein Kampf.

Countless signs in all languages at the Documentation Centre lead the way to the buses for the Eagle’s Nest. But if you walk five minutes in the opposite direction, into a the forest, you can see a small clearing with concrete remains of what was clearly a giant structure. A long wall embedded into the tree line is all that remains of the Berghof. Standing in the ruins of where Hitler’s most evil plans were formulated is a chilling experience. There is a plaque here, placed by the German government that indicates the location of Hitler’s home.

Climbing down the steep incline from the ruins of the Berghof, you can find the steel and concrete entrance into Hitler’s bunker system. A nearby red door forms the emergency doorway into Martin Bormann’s bunker.

Further down the path, is a small inn, the Hotel zum Turken. A popular resting stop on the mountain, Brahms once stayed here. The owner, Karl Schuster, a veteran of the Turkish Front in World War I, for which he named his guesthouse, refused to sell to the Nazis and was forcibly removed from the mountain.

The hotel was converted during the war into headquarters for the SS-Fuhrerleibwache, Hitler’s own personal bodyguard. Underground, as part of the tunneling project, the hotel contained SS prison cells, as well as living quarters for the guards, as well serving as a conduit between Bormann and Hitler’s bunkers.

As with most of Obersalzberg, the Hotel zum Turken was heavily damaged during the RAF raid. After the war, Schuster’s widow and daughter, petitioned to have their family property back, and in 1949 they purchased the hotel back from the German government. The inn was rebuilt and is open today.

While the Documentation Center up the hill oversees a rigidly supervised few hundred yards of the tunnels and bunkers to the public the other four miles remain sealed off. But privately owned, and not advertised at the visitor center, the Hotel zum Turken is the way into the large parts of the secrets of the mountain.

THE REMAINS OF AN UNDERGROUND CITY

Descending into the basement of the hotel down a narrow stone spiral staircase, the first thing you will encounter are the old wood-lined SS cells. The surface of the tunnels begin around 250 feet under the ground. These passageways would have linked Bormann’s underground chambers directly to the Hitler’s rooms underneath the Berghof. Dripping with condensation, lined with stalactites and green mold, the air is chillingly cold and undisturbed. If the Reich had fallen, it was from here that the war would have been plotted while the rest of Germany burned. Security was paramount. At the end of each tunnel and stairwell, a further hidden chamber was built behind the wall, where an MG-42 heavy machine gun team lay in wait for intruders.

Further down into the heart of the mountain is a room with the tiled remains of a bathtub. This was the underground living quarters of Hitler’s bodyguard. The wall next to subterranean barracks is mostly and crudely bricked up. Scrawled on the wall in rough paint, “access to Hitler’s house and private rooms.” written by the owners to help intrepid explorers navigate the labyrinth of tunnels.

Harper has explored further into the miles of secret tunnels. Some, she says, have become waterlogged and decrepit through decades of neglect. Another Berchtesgaden resident, historian and film maker, Florian Beierl has completed extensive research and mapping of the underground lair, in conjunction with the Bavarian state government, tracking down and interviewing many of the original engineers and exploring its deepest depths for a book, Inside Hitler’s Mountain.

His work tells the story of Hitler’s secret mountain headquarters, and how when the U.S. Army first entered the Berghof bunker they found cellars of wine, champagne, hordes of silver and shelves full of works of art from the galleries of Europe. Many mementoes from the bunkers, including Hitler’s personal folio of Shakespeare found their way back to random mantlepieces back in America.

A week before the Allies took Berchtesgaden, the SS started to burn the countless sensitive documents in giant pyres. According to Beierl’s research, these included Hitler’s old diaries, notebooks and confidential letters from his relations that he kept away from the public eye. One U.S. soldier discovered in the ashes a notebook called “Ideas and Creation of a Greater German Reich.” Others found vials of bottles for the cocktail of drugs that Hitler had been prescribed for what we now think was the onset of Parkinson’s disease.

Ultimately, Hitler never retreated to his mountain sanctuary, deciding to remain in Berlin where he committed suicide. The Allies found Berchtesgaden, Obersalzberg and the Eagle’s Nest deserted, most of its inhabitants escaping through an old 12th century salt mining trail in the mountain.

Today, visitors to Hitler’s second home can expect to find great information from the local museums. But still, large parts of the secret mountain complex remain untouched and forgotten. Deep underground, a chilling air blows through the now-empty rooms of Hitler’s subterranean city.

Luke Spencer