Working as a forest manager for a British teak company in the Burmese colony, James Howard “Billy” Williams came into contact with the domesticated Burmese elephant. He marveled at their power and intelligence, and even saw a sense of humor in the massive creatures used to carry timber.

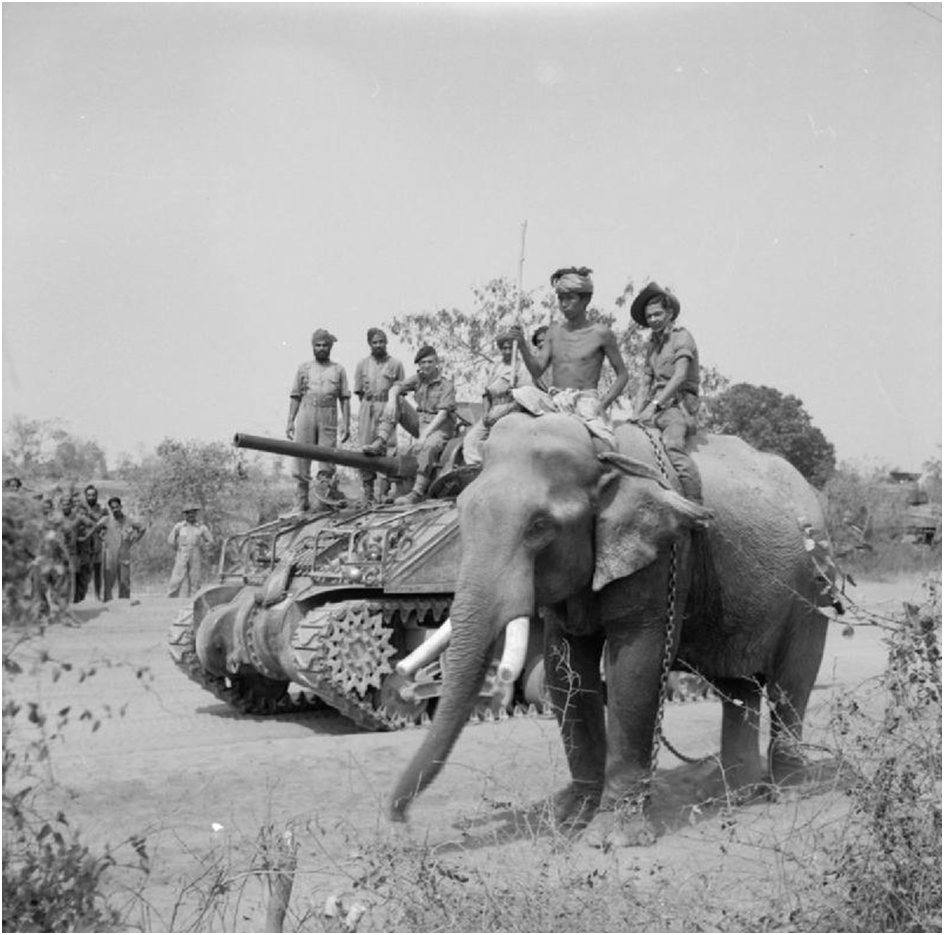

When Japanese forces entered Burma in 1942, Williams signed on to a special forces unit focused on guerrilla warfare. With them he saw the troop of elephants he admired carry timber for bridges and transport weaponry. But the most remarkable feat of the elephant company was the grueling journey to escape the Japanese military and reach India by way of the mountainous territory between them.

In her book Elephant Company, author Vicki Constantine Croke reveals how “Elephant Bill” and his brigade of pachyderms climbed a 300-foot cliff, but also discusses how the contemporary logging industry in Myanmar helps protect the Asian elephant and how elephants improve the lives of people. Simon Worrall from the National Geographic sat down with Croke to talk about the book.

What drew you into this story of James Howard “Billy” Williams, the fascinating but mostly forgotten figure from history?

It began with my interest in the elephants. The Jungle Book captured my attention as a child, and I loved hearing about people who had a sincere connection to animals. In that way, nothing has changed. Williams came to my attention when I found a book about elephants published by the University of Chicago Press. I saw in it a small black-and-white illustration of a man sitting on an elephant, looking over a valley from a cliff. The caption read: “J.H. Williams, helping refugees escape Burma in WWII.”

It grabbed me right away, and I began to research the topic. I dove into his numerous memoirs, as well as the memoir written by his wife, and I liked him immediately for his relation to the Asian elephant, which Williams said is nine-tenths love.

What is his story about?

From early in his life Williams said, “My way has always been the way of animals.” He had a profound empathy for the elephant, and tried to imagine the world as they did. Growing up in Cornwall, England Williams used this empathy to observe, and then predict where wrens would nest. He knew what these birds required for a nest, and he could reach into the grass and find a small nest with eggs based on his intuition.

Williams served in WWI, and the experience affected him tremendously. In 1920 he took a job with the Bombay Burma Trading Company as a forest assistant to move away from England and Western civilization. In time he became a talented doctor and trainer of elephants, and eventually he knew elephants was his life’s work. Before leaving Burma Williams could name a thousand elephants individually, which is something I find remarkable.

Tell us about Bandoola, the hero of the book.

Bandoola was a massive Asian elephant the same age as Williams, and it’s hard not to think of them as twins, only different species. Rather than being trained with force, a master mahout named Po Toke trained Bandoola with tenderness. Bandoola also was a rather humorous elephant, and would play games on his “oozie”, or rider. People who knew Bandoola saw him laugh when he did this. I’ve been around some elephants, and they do seem to have humor. You can see when they find something funny by the eyes and facial expression.

What is the relationship between elephants and people like James Howard Williams? It seems like much more than a rider-elephant relationship.

It’s a miraculous connection. William’s life changed when he met Bandoola, and first touching the elephant he sensed an energy run through them. Unlike others, Williams followed the mahouts’ ways of working with elephants. He trusted the mahouts, because they grew up with these elephants and could intuit things about them. They also respected and loved their elephants, and Williams tried to learn from them what he could.

Williams was a member of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), but what is that war organization?

Williams wanted to help when WWII started, and he knew he and his elephants would be an asset. But he didn’t want to be removed from the land. Rather, he saw himself on the ground, so to speak, and did so with the Force 136—the alternative name for SOE—a small special operations unit that moved quickly with small numbers. At his troops largest, Williams had command over 1,600 elephants along with their riders and mahouts, the National Geographic News reports.

Who was this Po Toke, who Williams called “my master in the study of elephants and my most trusted assistant in their management?”

We only know about Po Toke through Williams, but we know he was fifteen years older than Williams. The ‘master’ developed the notion of acting gentle towards the young elephants as he raised them. It was uncommon if not unheard of, and Po Toke even relieved Bandoola’s mother, Ma Shwe, from the more exhausting labor and gave her rest breaks.

Tell us about the “elephant stairway” Bandoola and the other elephants built.

It was incredible. To keep his elephants safe Williams had to move his elephants away from combat, and he decided to cross the border into Assam in India. At the last minute he was asked to help move sixty-four Ghurka women and children previously held captive by the Japanese. To get to safety meant crossing over five mountain ranges, and fighting broke out all around them at the time. They came to a cliff, but they couldn’t turn around, because the Japanese were behind them. In a truly amazing feat the troop decided to cut down vegetation and stone to make a staircase wide enough for the elephants’ feet, and led the fifty-three elephants up the 270-foot cliff. It tested Williams’ twenty-five years of work with elephants, as he had to put them to a task unfamiliar to them and under enormous pressure. The preparation lasted days, and the evacuation itself lasted three hours. Naturally Bandoola led the elephants.

What is the teak industry like today? Do people still use elephants in Myanmar?

They are still employed for logging, but taking to conservationists there is debate as to the future status of elephants there. It’s generally accepted that their involvement in the economy helps preserve Asian elephant populations; however, as the country lets in large companies, the elephants will lose their use, and perhaps will lose status as a result. Already in India there are many mahouts with their elephants on the streets, begging for food or money.

In your opinion, what makes elephants such special animals?

As early as 1920 Williams saw things in elephants that the scientific community has accepted more recently. They are intelligent; they have a sense of humor; they can use tools and recognize their own reflection. They even recognize death. Elephants have qualities that we often think of as specifically human.

You mentioned that elephants can change lives. How have elephants affected you?

It’s my hope that they have made me a better person, much like they did to Williams. He said that elephants taught him more about courage and trust than humans did. One thing I learned is that you can only trust those who have the strength to be trusted, those that a person can rely on, and elephants are a good example of that.