Many men fought and gave their lives in World War II. However, it’s not widely known that one particular pilot in the American military was African-American and Hispanic as well who fought to end segregation in the Miltary.

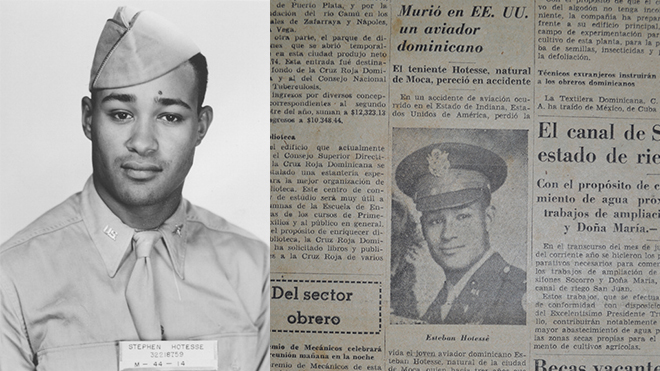

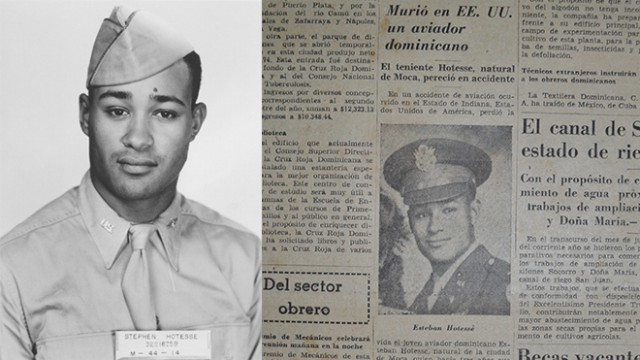

This man’s name was Esteban Hotesse; he was born in Moca, Dominican Republic, but moved with his family to New York when he was four years old. He was just 26 years old when he died during a military exercise on July 8, 1945, a little more than three years into his service.

When Hotesse enlisted in the Air Force on February 21, 1942, he became part of a 619 squadron. His group of 447 Tuskegee Airmen never flew in battle, but Hotesse did fight to end segregation laws and attitudes.

As a black Dominican, Hotesse joined a squadron that worked toward demolishing segregation policies in the military. This was during the hight of the Jim Crow issues; the fight to end segregation was taking place both inside and outside the military.

The name of the group Hotesse fought in was the Freeman Field Mutiny. One of their acts of resistance was in early 1945. He and the rest of the airmen tried to integrate an officers’ club at the airfield base in Indiana. All officers’ clubs were supposed to be integrated already, but this one in Indiana refused to follow the law.

During the group’s attempt to end segregation in the club by refusing to leave after being told to do so, over 100 black officers were arrested. Many years later, in 1995, the record of their arrest was finally expunged.

Hotesse is known for many things during the war: his attempts at ending segregation, being one of several African-American soldiers to fight, and his status as of the only known Hispanic soldier in the service. But his legacy would have gone unnoticed had it not been for a researcher in the Dominican Republic.

The reason Hotesse is being recognized now is because scholars studying the history of Dominicans in America discovered some of his papers during their research. Edward De Jesus noticed that an African-American Hispanic fought in the war and decided to do more research into Hotesse. He felt a personal connection with Hotesse because they are both Hispanics who moved to New York.

De Jesus and his research team were originally looking for World War II information in general when they stumbled upon reports of Hotesse’s actions in the war.

Three years later, their research was completed. De Jesus contacted Hotesse’s family; family members told him they have been waiting for all of this time for Hotesse to be recognized for all of the hard work he did with the army and with the segregation laws.