Odette Marie Céline Brailly was born in Amiens, France, in 1912. Her father died while fighting for their country in World War I. Her grandfather constantly reminded her of the heroism of her father because he wanted her to grow up strong.

As a child, she contracted polio and lost her sight for several years. She did not receive any sympathy from her grandfather.

In 1931, she married Roy Sansom, a hotel employee from England. They moved to London and had three daughters. When World War II broke out, the British war office put out the call for photos of the French coastline. Odette sent in a few that she had. Later, she was recruited by the Special Operations Executive (SOE), a group formed in the first year of the war to conduct intelligence, espionage, and sabotage missions throughout Western Europe.

Odette resisted at first because she wanted to stay home to raise her daughters. Eventually, she agreed to start the training, thinking that she would soon show that she was not qualified for the task.

To her surprise, she quickly took to the training in unarmed combat, weapons, Morse code, and sabotage techniques and found herself enjoying the courses. Still, with her husband already serving in the war, she was understandably reluctant to leave her children. She eventually relented and became one of only a few female spies in the Allied forces.

Odette reported to Peter Churchill in Cannes on the Mediterranean coast of southern France. She was charged with forming a spy network in Auxerre, a town 100 miles southeast of Paris. However, not long after she had arrived in Cannes the Italians invaded southern France, making it too dangerous for her to make the journey north to get there.

Instead, she began to work as a bicycle courier. She delivered messages from her spy cell to other members of the French Resistance. She also prepared intelligence reports that were flown to SOE headquarters in London.

One of her principal duties was working as a radio operator. This was a critical task as it was the main way to transmit information between Britain and France. It was also dangerous as the Gestapo monitored the airwaves searching for any unauthorized transmissions.

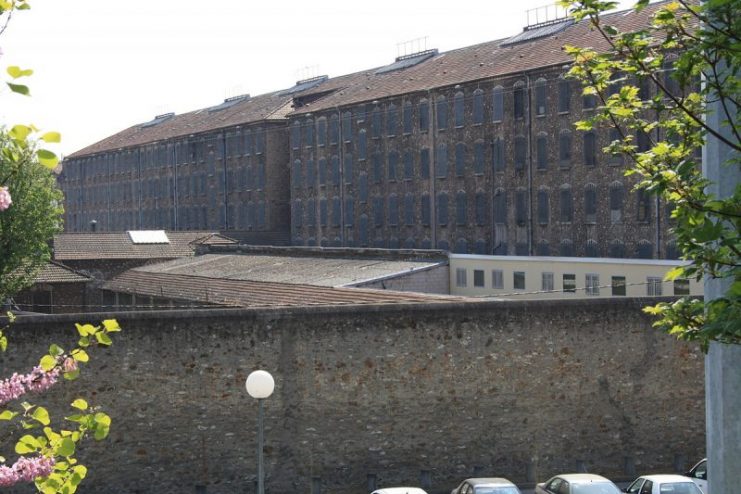

In 1943, Odette was betrayed by a German officer posing as an SOE operative. She was imprisoned in the Fresnes Prison south of Paris. While in custody, she was tortured by Gestapo officers who ripped off her toenails and press a hot iron to her spine. Despite the abuses of the Gestapo, Odette revealed no information.

While in prison, she managed to save the life of Peter Churchill by convincing the Gestapo that he was her husband and that, although she was indeed working for the French Resistance, Churchill was not involved in any way.

Odette was sentenced to death for two counts of espionage. When convicted, she replied that they would have to determine which count she was being killed for since she could only die once. She was then sent to Ravensbrück concentration camp. There, her guards nearly starved her to death.

As the war was nearing its end and the German soldiers realized they had lost, Odette was handed over to the Americans by the camp commandant, Fritz Suhren. He was hoping that such gestures would influence the Allies in letting him live. However, Odette testified against him at the Nuremberg trials, and he was executed for his war crimes.

In 1946, Odette was the first woman to ever receive the George Cross for gallantry. The George Cross is Britain’s highest non-military award. Violet Szabo and Noor Inayat Khan, two other female SOE operatives, were awarded the George Cross posthumously.

Odette died at home in Surrey, England, in 1995. She was 82 years old.

Odette was once quoted as saying that she was not afraid of being killed by the Nazis and that was the one thing that allowed her to endure. “They would have a dead body but they would not have me,” she said.