While news of wars throughout the global south often flies in and out of Western headlines with little fanfare or attention, the Iraqi invasion of Iran grabbed the attention of the Western press immediately.

When then-Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein initially declared war on Iran over a dubious territorial dispute, he could not have predicted the duration or the ferocity of the war that would follow. The war would last eight years, during which hundreds of thousands were killed (according to conservative estimates).

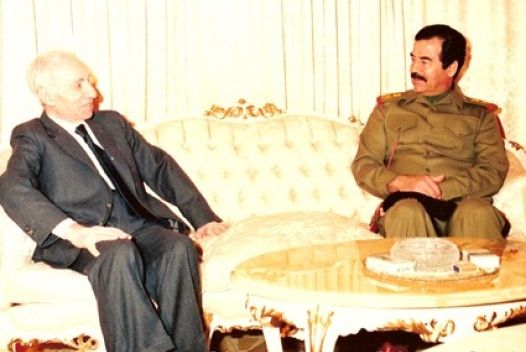

The cultural tension that existed between the new government in Iran, headed by Ayatollah Khomeini, and Saddam Hussein’s Sunni Baath party government would drag a seemingly local territorial dispute onto the world stage with acts of gratuitous destruction and barbarous disregard for human life.

Hussein’s decision to employ chemical weapons against an ethnic minority he distrusted within the borders of his own country figures largely in the list of reasons that the conflict drew the amount of condemnation and the strong international reaction that it did.

Hussein regarded the Kurds of Halabja as conspiratorial enemies, and his decision to attack them with nerve agents shocked the global community at a time when the world had very recently seen the effects of such weapons during the Vietnam War.

It has been argued that it was suspicion of his neighbours that led to the onset of the war in the first place. While Hussein regarded the Iranians as a threat to his power on the heels of the revolution that brought them to power, the Ayatollah saw Hussein as a brutal dictator engaged in wholesale religious oppression of Iraq’s Shia majority. Their deep-seated contempt for one another caused the war to continue far past the point of futility.

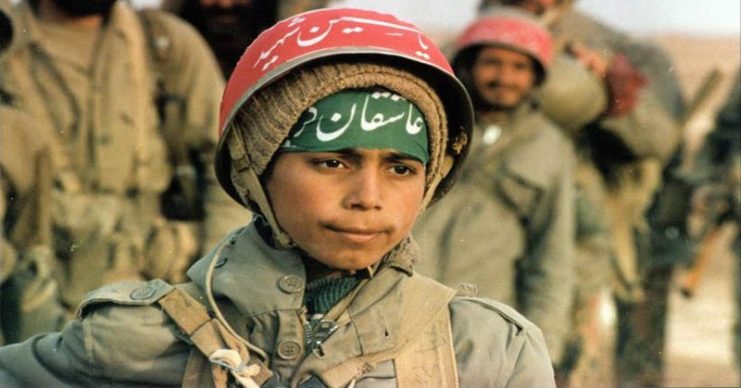

Saddam’s pre-emptive strike against the Iranians was foolhardy – the Iranians were nowhere near as disorganized as he expected, and a war of attrition ensued with each side employing progressively more brutal measures to weaken their enemies’ resolve.

Civilians died by the thousands as each side bombarded the other’s cities, and neither would accept a ceasefire despite little ground being gained in either direction.

The war quickly grew to involve trade with each side attacking the other’s oil shipments and cargo vessels. Still, no ground was gained and when a sufficient number of Kuwaiti vessels were attacked that threatened the international oil trade, both the United States and Russia responded to its calls for protection. This international intervention was ultimately to the detriment of Iran more than Iraq, and the Ayatollah very reluctantly accepted a ceasefire in July 1988.

It quickly became clear that after eight years of fighting, neither side had achieved its aims – neither Iraq’s wish to crush the upstart Ayatollah nor the latter’s desire to capitalize on his foe’s strategic blunder.

While the Iraqi leader was quick to claim victory, the ruin that the war had wrought upon his country was clear and irreversible. Likewise in Iran, many had begun to question the Ayatollah’s competence in the year before his death shortly after the war’s end.

Hussein would miscalculate his tactical advantage yet again shortly afterwards in a desperate attempt to recover and rebuild the nation that he had just helped to destroy from within. He committed Iraq to an invasion of Kuwait that quickly invoked an American military response.

Shortly after Iraq commenced its invasion, the same forces that had aided Iraq not long before returned to push its forces back within their own borders. It was not the first, but it would be the last time that Iraq would commit itself to a path of aggression that resulted in untold national hardship.