On 10 June 1918, during the Battle of Belleau Wood, 44-year-old Marine Corps First Sergeant Dan Daly, armed with a pistol and hand grenades, single-handedly attacked and destroyed an enemy machine gun emplacement.

It was the kind of action from which legends are born, but it was not even Daly’s most famous action that month. He is better known for his battle leadership four days earlier, when he urged his 73rd Machine Gun Company forward with words now legendary in the Marine Corps: “Come on, you sons of *’s; do you want to live forever?”

Marine Corps tradition holds that the term “Devil Dog” was coined when someone in the German high command asked of the Marines on that same battlefield, “Wer sind diese teufelshunde?” (Who are these Devil Dogs?)

There is some doubt as to the veracity of the quote, but there is no doubt that Dan Daly, all five-feet-six-inches and 130-some pounds of him, proved the adage, “It’s not the size of the dog in the fight; it’s the size of the fight in the dog.”

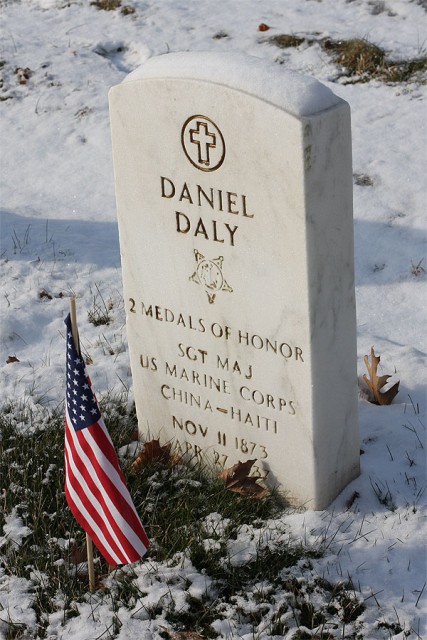

Daniel Joseph Daly was born on 11 November 1873 in Glen Cove, New York. Not much is known of his formative years except that he sold newspapers and was good with his fists. He was 25 years old when he joined the Marine Corps on January 10, 1899, with the idea of serving in the Spanish-American War.

By the time his basic training was complete, the war was over, and he was instead assigned to the Asiatic fleet. It wouldn’t be long, though, before he saw action.

In May of 1900, in the midst of the Chinese Boxer Rebellion, Daly was part of a Marine contingent sent to Beijing when the Boxers laid siege to the international compound there. On July 14, about midway through the siege, Marine Captain Newt Hall was ordered to build a barricade to expand the U.S. position.

He took Private Dan Daly and went forward to reconnoiter the area. Captain Hall then returned to gather men and materials to build fortifications, leaving Daly to defend a critical position on the Tartar Wall alone with just a rifle and bayonet.

Recognizing the tenuous position he was leaving Private Daly in, Captain Hall told Daly that he could not order him to stay there, to which Daly reportedly replied “See you in the morning, Captain.”

During the night, as Captain Hall had feared, the Chinese repeatedly attacked Daly’s exposed position on the wall, but Private Daly prevailed, and when Hall returned in the morning with reinforcements, the ground in front of Daly’s position strewn with enemy dead.

Private Daly was awarded his first Medal of Honor for his actions that night. The citation simply reads, “In the presence of the enemy during the battle of Peking, China, 14 August 1900, Daly distinguished himself by meritorious conduct.”

Fifteen years later, after several tours at sea and postings at Marine barracks in the United States and Puerto Rico, Gunnery Sergeant Daly was assigned to United States occupation forces in Haiti. On 24 October, 1915 he was the senior noncommissioned officer on a mounted reconnaissance patrol sent to locate Cacos rebel strongholds in the interior of the island.

After dark that evening, as the detachment crossed a river in a deep ravine, they were ambushed from three sides by a force of some 400 Cacos. The Marines fought their way to a tenable position and established a defensive perimeter, but several horses and a mule carrying their only machine gun had been lost in the crossing.

Once the defenses were in place, Gunnery Sergeant Daly left the safety of the perimeter under cover of darkness and crept back to the river crossing in search of the machine gun, using his knife to dispatch several Cacos he encountered along the way.

At the river, with no cover from enemy fire, he dove repeatedly to find the mule and to detach and recover the machine gun and ammunition. He then slipped back to the Marines’ position carrying a load that had previously been assigned to a beast of burden and had the weapon assembled and emplaced before dawn.

By first light, the Marines were organized into three squads. They executed a bold attack in three directions, surprising and scattering the enemy. After the mission was complete, the detachment commander, Major Smedley D. Butler, recommended Gunnery Sergeant Daly for his second Medal of Honor.

The citation for which reads, in part, “Gunnery Sergeant Daly fought with exceptional gallantry against heavy odds throughout this action.” Smedley Butler would go on to earn a second Medal of Honor himself later in the same conflict, becoming one of only two Marines to earn two Medals of Honor for action in separate conflicts. The other, of course, was Dan Daly, whom Butler would later call “The fightenist Marine I ever knew.”

First Sergeant Dan Daly and the 73rd Machine Gun Company, 6th Marine Regiment rolled into France in November, 1917. In late May, 1918, they moved to positions southwest of Belleau Wood, where Daly’s actions over six days in June would secure his status as a Marine Corps Legend. The citation for the Navy Cross he earned there lists “repeated acts of heroism.” On June 5th, he risked his life to put out a fire at an ammunition dump.

On June 7th, while his unit was under heavy bombardment, he visited all of his machine gun emplacements, then “posted over a large portion of the front, to cheer his men.” Then, on 10 June, after his unassisted destruction of a machine gun emplacement, he repeatedly brought in wounded Marines under fire. Daly was recommended for a Medal of Honor for his actions, but the award was reportedly reduced because someone in the chain of command balked at the idea of anyone receiving three Medals of Honor.

First Sergeant Daly was wounded on June 21, 1918, but went on to fight in two more offensives before receiving wounds that took him out of combat. He remained in Europe after the Armistice, serving in the Occupation of Germany. In 1919, he was assigned to the Fleet Marine Corps Reserve. He retired from the Marine Corps as a Sergeant Major on 6 February, 1929.

In retirement, Dan Daly avoided publicity and was averse to any attention paid to his awards, saying that all medals were “a lot of foolishness.” He died on April 27, 1937, at the age of 63 and is buried at Cypress Hills National Cemetery.