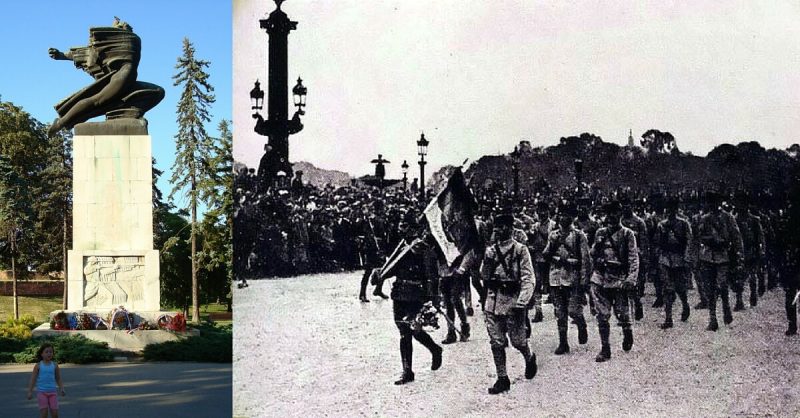

On the banks of the Danube and Sava rivers stands a statue of a woman, her hands balled into fists, underneath which a plaque contains the words; “Let us love France as she loved us”.

Over a century has passed since World War 1, and the once-strong and jovial partnership that had existed between Serbia and France has all but been forgotten. But the grand Monument of Gratitude, designed as a “thank you” to France for its assistance in WW1, still stands to this day, in recognition of what was once a great partnership.

Stanislav Stretenovic, historian of the Belgrade-based Institute of Contemporary History, believes the statue is unique in its intention. “As far as I know, it is the world’s only monument dedicated to a foreign country, and not just a leader or a people.”

After the devastation of the Gallipoli campaign, France sent their troops to the Greek port of Thessaloniki on October 5, 1915, planning to open a new front and come to the aid of their Serbian allies.

The residing King of Serbia, Peter I, was educated in a French school and grew up with a fondness and passion for French culture. This may be what influenced him to co-operate with the French in the Franco-Prussian war in 1870 and 1871, an alliance which afforded a positive view of France in the minds of the Serbian aristocracy.

When WW1 began, Serbia was thrust into the French public’s conciousness as newspapers began headlining articles about the Serbian victories over the German-led Central Powers. “Serbia was portrayed as a valiant martyr,” says Stretenovic. “The French heaped praise on Serbia’s courageous warrior-peasants, with whom many French soldiers identified.”

Throughout the war French citizens hosted over 3,000 Serbians Students and a nationwide “Serbian Day” was celebrated on March 26, 1915 in schools across the country.

Despite the cheerleading from France, Serbia’s military became emaciated by enemy forces, so France sent a team of aviators, navy officials and medical staff to assist the dilapidated Serbian regiments. Still, the army was exhausted by an epidemic of typhoid, repeated enemy offensives, and attacks on all fronts. Its soldiers were forced to retreat over the cold Albania and Montenegro mountains, where Serbia lost a further third of its entire military.

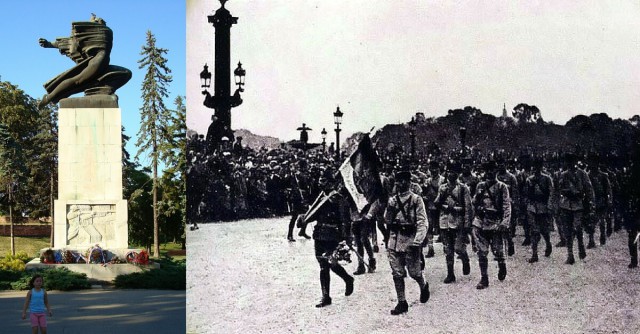

Again, France stepped in to help its Serbian ally by launching the Salonika Mission, which saw 350,000 French and British troops sent, along with their navy, to rescue Serbian forces stranded on the coast of Albania, the France 24 reports.

Finally, Serbian forces were able to liberate their capital in Belgrade on November 1, 1918, marching alongside the French Army. “Glory to our eternal France!” proclaimed Serbian minister Kosta Kumanudi, at the inauguration of the Monument of Gratitude to France, 12 years after the cease-fire.

Fast-forward one hundred years and almost no one remembers the immensely beneficial bond between Serbia and France. What happened? After the war the country’s communist rulers sought to downplay France’s involvement in saving Serbia.

“They didn’t want people to talk about what happened before their arrival,” Stretenovic said. “They wanted their struggle [against Germany] to be the sole reference. History started with them.”

And so a powerful friendship and immensely beneficial bond between two great countries was caused to slide out of public consciousness and into the depths of history books.