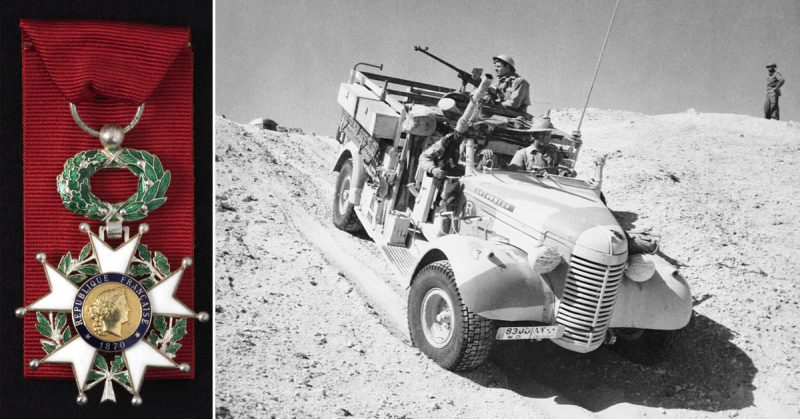

The adage of better late than never certainly applies to Mike Sadler, now 98, who was recently presented with an award for his bravery during WWII. Mr. Sadler was made a Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur at an awards ceremony undertaken by the French Defence Attaché, Colonel Antoine de Loustal.

The private ceremony held in London was attended by family, friends, delegates from the French Embassy, and former members of the SAS.

His feats of bravery during the war read like a movie script.

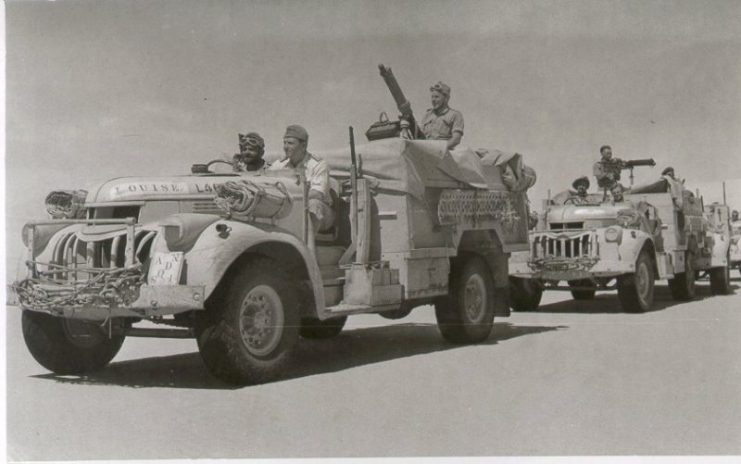

Mike Sadler joined the Long Range Desert Group in 1941 and was based in the North African desert. Lieutenant David Stirling brought the SAS (Special Air Service) into service, and Mr. Sadler was transferred to the new unit when they began launching raids in Libya.

He became their top navigator as he had a unique talent for being able to navigate vast expanses of desert, without the aid of maps, to guide the raiding parties to their targets.

In December 1941, Mike Sadler was one member of a six-man team led by Lieutenant Blair ‘Paddy’ Mayne, who became one of the most highly decorated British soldiers of WWII. The team raided the Wadi Tamet airfield and sabotaged 24 aircraft and a fuel depot.

On the 26th July 1942, he also navigated the route for 18 vehicles loaded with Vickers K machine guns through 70 miles of featureless desert. Using no lights or maps, he managed to guide the convoy to within 200 feet of the Sidi Haneish airfield.

Once they arrived at the airfield, the jeeps drove in and out around the planes, resulting in the destruction of at least 37 aircraft. Sadly, one member of the team was killed in the attack and was buried in the sand near the airfield.

Mike Sadler was awarded the Military Medal for the raids of the Sidi Haneish and Wadi Tamet raids.

Mike Sadler was also one of the members of the last raid that Lieutenant Stirling and the SAS undertook during the desert war. In January 1943, they set off across the Tunisian Desert to try and link up with the British-American 1st Army, but on the journey they were ambushed by a German patrol. Stirling was captured and spent the rest of the war as a prisoner at Colditz, but Sadler set off with one fellow soldier and an Arabic speaking Frenchman.

He successfully guided the three-man party across 100 miles of desert without provisions or any maps, to eventually link up with the 1st Army. An American war journalist, A J Liebling, who happened to witness the arrival of Mr. Sadler and his small party wrote, “The eyes of this fellow were round, and sky blue and his hair and whiskers were very fair. His beard began well under his chin, giving him the air of an emaciated and slightly dotty Paul Verlaine.”

From the deserts of North Africa, he moved on with the SAS to Italy and France before forming an intelligence unit.

On the 7th August 1944, Sadler took part in Operation Houndworth and parachuted into the Loire region in France. The operation was designed to destroy German fuel depots and encourage the local resistance groups so that Panzer Divisions would be slowed down or prevented from moving north.

Hitler had issued an instruction that any captured parachutist was to be summarily shot so when Nazi soldiers attacked the two-jeep convoy that he was in he knew he had to fight for his life. Sadler fought on while the second jeep fled and for this act of bravery he was awarded the Military Cross. Mike Sadler ended the war with the rank of major.

Mr. Sadler, who is now almost blind, refused to give a speech at his medal ceremony, quipping that he could not read his notes. He later told journalists that he remembered the men that had fought alongside him, those that made it home and those that did not survive to be granted this honor by France.

In 2014, then French President François Hollande ordered that all British soldiers that fought to liberate France were to be awarded the Légion d’honneur.

As Colonel Antoine de Loustal placed the medal with its distinctive red ribbon in the hands of one of the last British wartime heroes he said, ‘We shall not forget. We will never forget.’