Several millennia ago men were in an unusual position. According to recent studies, genetic diversity–specifically the diversity of the Y-chromosome–virtually collapsed over the course of two thousand years. This collapse was so devastating that there was possibly only one man for every seventeen women.

This conundrum had both anthropologists and biologists baffled, but now researchers at Stanford University think they have discovered a simple explanation. Their argument is that this drop in genetic diversity is due to generations of war between patrilineal clans, whose membership was determined by male ancestors.

Chen Zeng, a sociology undergraduate at Stanford, came up with the outline for the idea after reading hours of blog posts that speculated on what is now called the “Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck.”

He shared his ideas with Alan Aw, his high school classmate who was now a Stanford undergraduate in mathematical and computational science.

They felt the idea had enough merit that they brought it to Marcus Feldman, a biology professor in Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences. Aw, Zeng and Feldman published their results in the May 25 edition of Nature Communications.

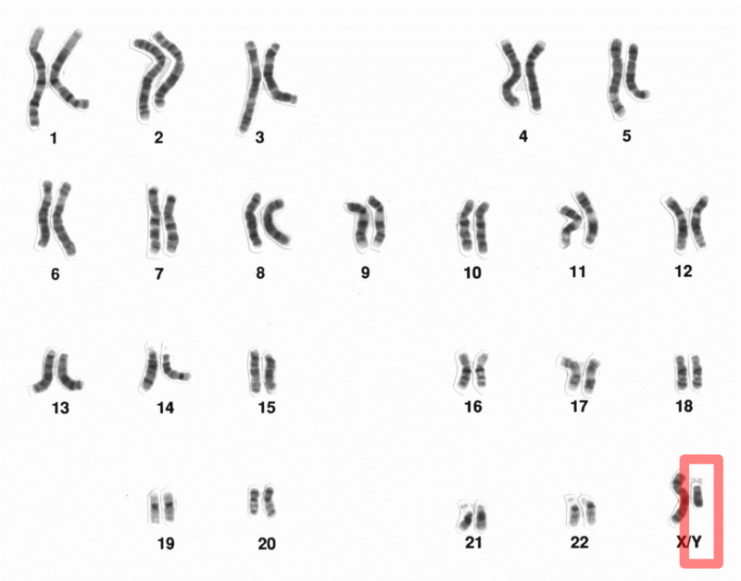

There is a precedent for the tendency of human genetic diversity to drop every once in a while, but this particular Y-chromosome bottleneck, the evidence for which is drawn from genetic patterns in modern humans, is a particularly strange case for a few reasons.

The first is because it is observed only in men, and more precisely, only through genes on the Y-chromosome, which is passed from fathers to their sons.

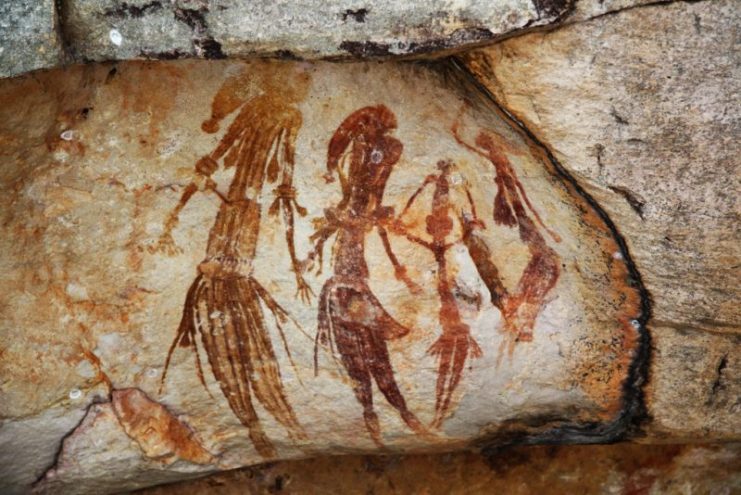

The second is that the bottleneck is far more recent than other biologically similar events, suggesting that the origins of the issue may relate to changes in social structures–and social structures at the time were indeed going through rapid changes.

The social and economic milieu had gone through an almost complete upheaval, from tribal hunter-gatherer societies to those centered around agriculture.

For us, this happened nearly twelve thousand years ago, but at the time of the Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck, that would have been a mere five thousand years ago.

Societies had developed and grown in complexity around extended kinship groups, many of which were patrilineal clans. While women effectively entered the clan upon marriage, the men in each clan were all related through male ancestors, and therefore would all have the same Y-chromosome.

Naturally, this would only apply to each individual clan. Given geographical considerations, time, and intermarriage between clans, what was once a significant amount of variation in Y-chromosome differences would shrink to favor those who were strongest according to natural selection–and that is without the consideration of the additional wars fought for dominance and supremacy, which would add an extra factor into the ever-shrinking pool of Y-chromosomes.

Testing of the hypothesis was done using mathematical models and computer simulations in which men fought and died for the resources their clans required for survival.

The simulations displayed that wars between patrilineal clans caused drastic reductions in Y chromosome diversity over time, while conflict between the control group of non-patrilineal clans–defined as groups where both men and women could move between clans–did not.

The model used by Zeng, Aw and Feldman accounted for the observation that some male lineages survived the Y-chromosome bottleneck. A few of the lineages that were connected with the patrilineal clan model expanded dramatically, but not necessarily others.

This research has since been expanded to include its framework in other areas where genetic patterns can be explained through cultural interactions influenced by history and geography.

Read another story from us: The Fall of the Aztecs, The Bloody Path to Tenochtitlan

According to Feldman, this work is an unusual example of interdisciplinary undergraduate-led research that spanned sociology, mathematics, and biology, with implications for deepening the understanding of the role of culture in human evolution.