As a child, Takei and his family lived in an internment camp in Arkansas, during the Second World War. After the Pearl Harbor attack on Dec. 7, 1941, all Americans of Japanese descent were taken out of their houses and businesses and placed in tar paper shacks across the country. They never touched any Germans or Italians, although we were fighting against them as well. Same situation was in Hawaii, where the Japanese population was left alone due to the fact that they were of Japanese descent from the East Coast and from the Midwest.

Takei explained why they didn’t touch the Hawaiian Japanese population. According to his calculations, at that time, 40 percent of the population in Hawaii was of Japanese descent. Therefore, if they would have all been arrested, the island’s economy would have collapsed. It was a completely different situation than on the West Coast, where if you were 1/8 Japanese, you were sent off to one of the camps.

But the raids didn’t stop there. They soon began searching orphanages. They would take all the children into custody, one thing Takei was never able to understand: why did they think a less than a year old child would hurt anyone, or would threaten the safety of the country. He described the round up as ‘irrational’ and ‘racist’, recalling how his family had only two weeks notice before they would be kicked out of their house and moved to a camp. “I remember that day,” he said.

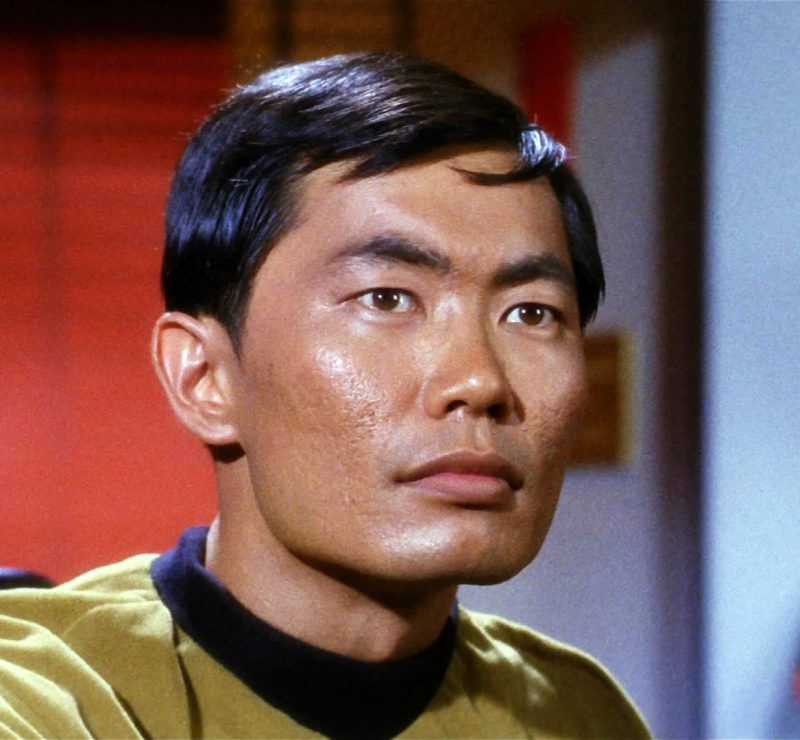

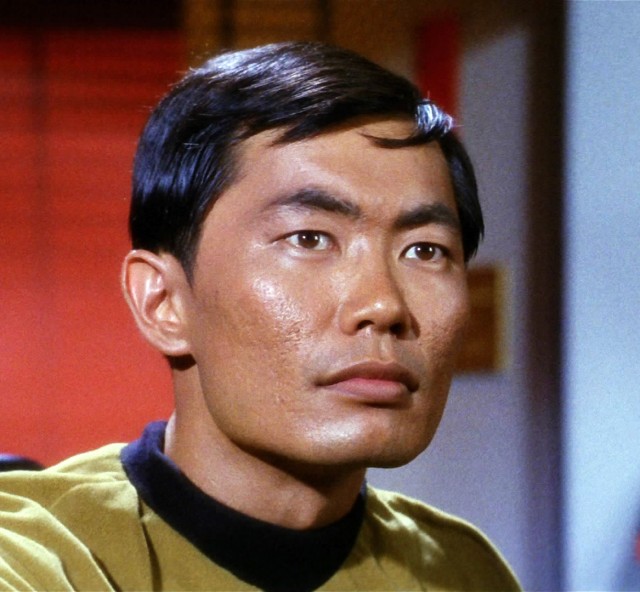

Little George was only five years old when his mother woke everyone up, with tears in her eyes. With guns pointing at them they were walked out of their house and taken into a horse stall at Santa Anita Park, where they had to live until the camps were ready for them to move in. He found the experience ‘degrading’ and ‘humiliating’.

A few months later they were taken to a camp in Arkansas. They stayed there, in their little tar paper shack surrounded by barbed wire, guard towers and with guns constantly pointing at them, throughout the war, the DallasVoice.com reports.

When the war was over, every ‘prisoner’ had the right to leave the camp. They would each receive a bus ticket to any destination in the U.S. and an extra $20.

Takei’s father went back to Los Angeles, where he found a house and a job as a dishwasher. Takei didn’t like the house or the neighborhood, but they didn’t stay long there either. Shortly after, his father bought a dry cleaning business in East L.A, where they all enjoyed living.