Maracaibo is the second largest city in Venezuela with a population of 1.3 million people. It is situated along the waterway that runs from Lake Maracaibo (the largest lake in South America) to the Caribbean Sea.

Maracaibo was originally named New Nurnberg when it was founded by Germans in 1529. It was abandoned when the settlement came under repeated attacks by native tribes. The Spanish came along in 1574 and resettled it. Renamed Maracaibo, it came under repeated attacks by buccaneers in the 1600s.

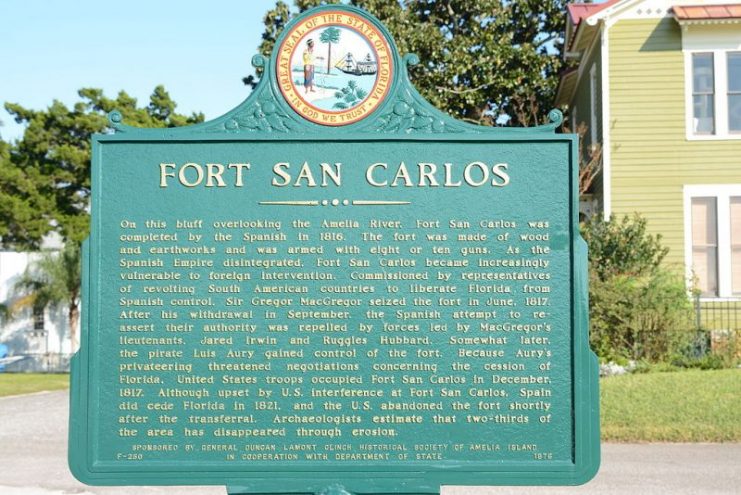

In 1623, the Spanish built an impressive fort on the island of San Carlos in order to protect the entrance to Lake Maracaibo and prevent access to the lands beyond.

In 1823, Maracaibo was attacked by Colombian and Venezuelan forces who routed the Spanish army in the Battle of Carabobo, which effectively marks the end of Spanish power in South America.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, developing countries would accept loans from European powers. The countries accepting the loans were seldom in a position to actually repay the loans given the continual power transfers and instability in their political situations.

So the European countries were able to dictate harsh terms, including high interest and automatic deduction of the interest from the principal so that the amount of money received was often far lower than the amount loaned.

In 1899, José Cipriano Castro amassed a private army and took over the government of Venezuela. US Secretary of State Elihu Root called Castro a “crazy brute,” which seems like a reasonable assessment in light of the way he ruthlessly put down rebellions and murdered political opponents.

Castro decided to solve the problem of his country’s debts with European nations by simply refusing to pay them. Britain, who was owed most with a $15 million loan from 1881 and also Germany, angered by the Venezuelan seizure of a railway owned by a German company, were the major powers most affected by Castro’s decision.

Castro seems to have been emboldened by the USA’s Monroe Doctrine, which stated that the American government would consider any interference by European countries in the Americas as an act of aggression to be met with force from the US military.

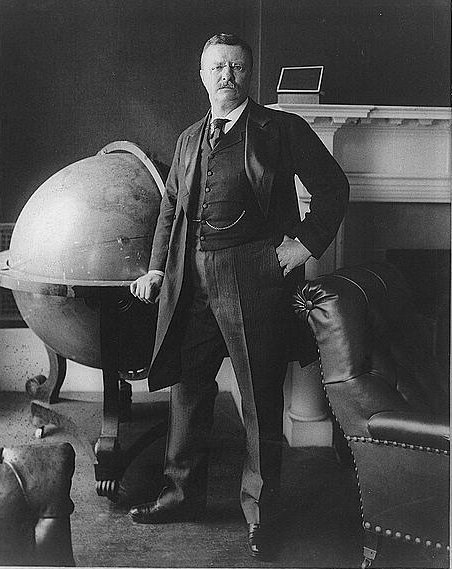

However, President Theodore Roosevelt had backed away from that doctrine when he publicly proclaimed that any South American country that antagonized a European country should be dealt with by that European country.

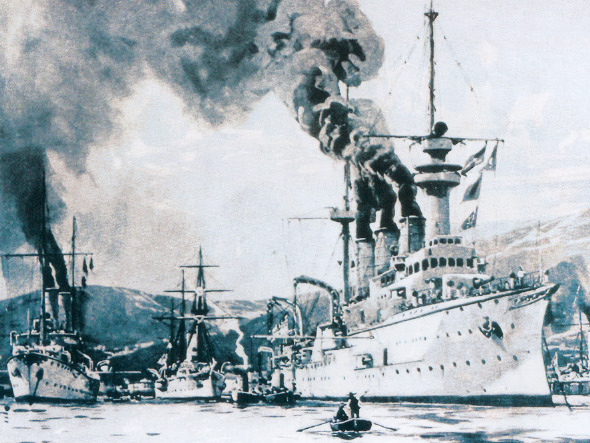

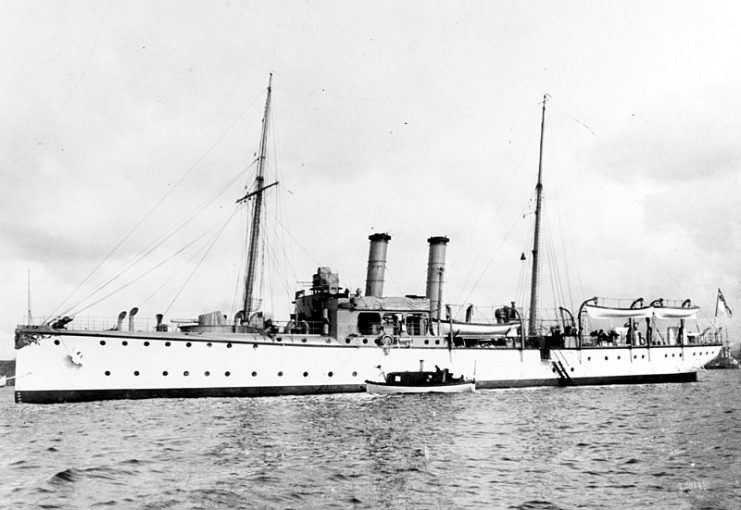

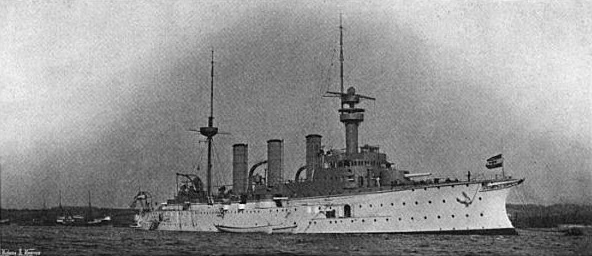

After pushing for either repayment or arbitration for some time, the British and Germans joined forces to blockade Venezuela beginning in December 1902. This was a commonplace mission for the British, but Kaiser Wilhelm II had recently commissioned the Imperial German Navy and he was eager to show it off. While the British deployed a cruiser, a sloop, and a few other ships, the Germans sent three cruisers and a gunboat.

The Venezuelan Navy – two gunboats, a yacht, and a tugboat – was quickly defeated in two days. Two of their ships were so dilapidated that the Germans sunk them rather than capture and tow them. Castro responded by capturing a British merchant ship and holding 200 British and German residents as hostages.

Meanwhile, Roosevelt was having second thoughts about the importance of the Monroe Doctrine. In part, this was influenced by the Germans scouting the Venezuelan island of Margarita as a potential location for a base in the Caribbean.

Therefore, he pushed for all sides to come to arbitration and later took credit for convincing the Germans to agree by threatening to send the US Navy against them if they didn’t – though no evidence has been found to support his claim.

In 1903, two of the German ships chased a schooner that had slipped through the blockade and headed for Maracaibo. The ships came to Fort San Carlos and retreated after coming under fire by the fort while having difficulty navigating the shallow waters.

Four days later, the Germans returned with more firepower and attacked the fort. After eight hours of shelling, the fort was destroyed, and 25 civilians had been killed in the nearby town. With the victory came a loss of sympathy for Germany from both the US and the UK, but also a new willingness to arbitrate from Castro.

The sides met in Washington for the arbitration process in February of 1903. The result was a restructuring of Venezuela’s debt with more favorable terms for Britain and Germany. This upset the Americans who had made their own loans to Venezuela so it was agreed to take the matter to the International Court of Arbitration in the Hague.

The end result was Roosevelt’s Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine which stated America’s right to intervene in the economic affairs of the small Caribbean and Central American countries in order to prevent European interference. This would have long-term repercussions up to and including the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962.