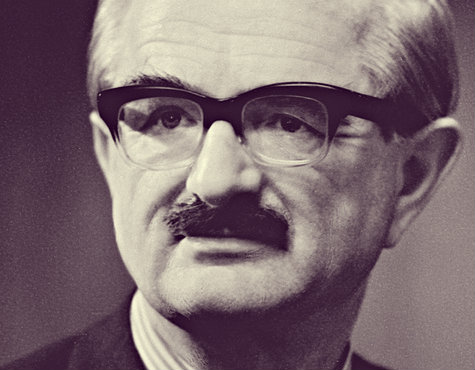

Sir Arthur Bonsall – WWII codebreaker and former head of GCHQ, Bletchley Park’s successor after WWII – passed away last November 26, 2014 at the old age of 97. Let us look at the legacy the WWII codebreaking veteran left.

Sir Arthur Bonsall played a vital role in the interception and breaking of German Luftwaffe communications during the Battle of Britain and afterwards, in Germany’s strategic bombing. Years after the war, he was appointed head of the British central intelligence hub’s postwar successor, the GCHQ.

Like the other codebreakers, the indoctrination about the need for sheer secrecy when it came to the operations in Bletchley park was deeply ingrained in Sir Arthur Bonsall. When the time came that GCHQ moved to its “doughnut” office just on the outskirts of Cheltenham some ten years ago and the four-letter acronym that stood for the office’s name, the Government Communications Headquarters, started to emerge printed on the buses of the city, Sir Arthur Bonsall confessed to being shocked.

My grandchildren now had the right to ask me what I did during the Second World War. It dawned on me that I have to start remembering the things that a did within those tumultuous years. It was a big change for me, he said.

In an interview with the BBC just last year, Sir Arthur Bonsall stated that the British government did everything they could to bury the secrets of Bletchley Park. The standing policy, he added, was that if anyone asked, no answer was to be given.

Officials of GCHQ did not even tell those closest to them – their immediate family – about the nature of their work. That was until Time magazine blew the cover up way back in 1976. Sir Arthur Bonsall went on to admit that his family did not know about his job until later than that.

This approach in his job was reflected in 1978. That time, then foreign secretary David Owen released a statement saying that the codebreakers of Bletchley Park could now open up about their jobs during the Second World war particularly about breaking the Germans’ Enigma codes. However, Owen added that they are not allowed to divulge “any technical details of the work”.

Sir Arthur Bonsall, who was then the head of GCHQ, then stressed out that “no records about this second aspect are being released to the Public Record Office” and that not one individual concerned about the matter was absolved from the oaths they gave at that time.

Looking back at the Life of Sir Arthur Bonsall

Sir Arthur Bonsall, or Bill to his loved ones, was born in Middlesbrough to Wilfred and Sarah. They family, eventually, moved to Welwyn Garden City in Hertfordshire where Bill got his education at the Bishop’s Stortford college. later on, he got his second-class modern language degree at St Catharine’s College in Cambridge.

Sir Arthur Bonsall enlisted for the army but failed in one of the medical tests required. So, he joined the Air Ministry in 1940 instead. Later on, Martin Charlesworth, one of the Cambridge heads indoctrinated in the secret works of Bletchley Park where the Government Code & Cypher School was based, spotted Bill’s talents.

So, Charlestown invited Sir Arthur Bonsall, together with another candidate, in his rooms. The first head of GC&CS, Alastair Denniston, together with John Tiltman, his colleague, were waiting inside to interview them. Bonsall recounted his experience in the book The Secrets of Station X authored by Michael Smith and published way back in 1998. According to him, the two men asked them [the candidates] if they wanted to get involved in some war works that required secrecy. When they said yes, Denniston and Tiltman told them that they would be contacted again. After a few weeks passed, Bonsall received a letter that instructed him to go to Bletchley Junction without the knowledge of anyone, not even his parents. He was, then, met and was taken into the Mansion where he signed the Official Secrets Act.

From Codebreaker to GCHQ Head

The following day, Sir Arthur Bonsall was informed that he would be working on the radio communications of the Luftwaffe, Germany’s air force. In just minutes, Bonsall found himself seated at a trestle table and copying codes on to a large sheet of paper. The Bletchley Park section he belonged to worked with low-level codes of the Luftwaffe bombers. Through their work, they were able to track the war planes which were flying from France on their way to campaigns in Britain.

In his own words, Sir Arthur Bonsall described his Bletchley park work as a “no great brainpower and no special machinery” required. All his section needed was a paper and a pencil for its operation.

His job might have been easy in those times but the turf wars existing within the British administration made things difficult. The Air Ministry maintained the view that Bletchley Park’s work should be limited to breaking the codes and that the analysis and interpretation of the decoded messages was the job for the ministry’s intelligence section.

Sir Arthur Bonsall maintained how the Air Ministry failed to realize that the codebreakers in Bletchley, the ones who intercepted the codes, were also the best ones, oftentimes, to interpret them. He pointed out that the proper interpretation of the decoded Luftwaffe messages depended, at most, to the context and nature of the communications between the German pilots. These information were available to the signals intelligence [Sigint] working in Bletchley Park. However, the intelligence section of the Air Ministry did not have these advantages.

It was not until the middle of the Second World War that the Air Ministry accepted the realization that the Bletchley Park section had found the speediest way not just to intercept and decrypt but to interpret the coded messages as well.

After WWII ended, Sir Arthur Bonsall moved up in ranks within the GCHQ. He headed sections which seized Soviet communication with the Warsaw Pact countries and covered the Middle East during the crisis in the Suez. Finally, he became GCHQ’s sixth director in 1973. It was those days, he said, that one didn’t apply for a promotion as rising up in ranks was per recommendation. Fortunately, his predecessor, Joe Hooper, saw the potential in Sir Arthur Bonsall and recommended him for the position.

Bonsall held that position until 1978.

Furthermore, he was appointed CBE in 1957 and KCMG in 1977.

His wife, Joan Wingfield, was also a codebreaker — working on Italian navy codes in Bletchley Park. The two married in 1941 and went on to have four sons and three daughters. Joan already passed away way back in 1990.

Goodbye, WWII codebreaker and former GCHQ director Sir Arthur Bonsall [born 25 June 1917; died 26 November 2014]!