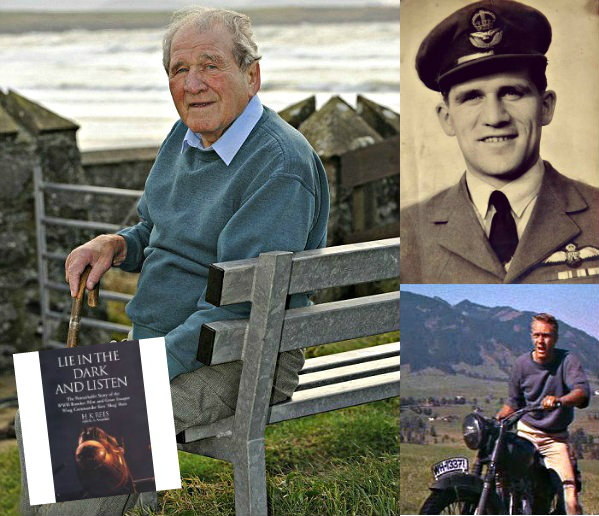

Ken Rees was piloting a Wellington bomber in a mine-laying operation in Norway in October of 1942 when it was shot down. He was able to crash land the aircraft in a lake and clamber up to the shore along with two other crew members; the other two who were with them lost their lives. Though they were saved from getting toasted or drowned, they were, nevertheless, captured by the enemy. After going through an interrogation, Ken Rees was sent to Stalag Luft III, the prison camp for captured Allied airmen.

While in prison, Ken Rees became the ‘headache’ of his captors. He was so troublesome and was fond of needling the prison guards that he was a regular guest of the ‘cooler’ — Stalag Luft’s punishment block.

The antagonism Ken Rees showed towards the German guards of the prison camp stemmed from his anger when he learned that his brother-in-law – a pilot like himself – was machine-gunned by a German war plane. Reportedly, Rees’ brother-in-law had bailed out of his burning Hurricane and was floating earthward when the German craft did the deed.

As Ken Rees recounted in his later years, he, along with the others, had vowed to agitate the Germans as they felt almost invincible, so capable and were well-trained.

When the time came that Squadron Leader Roger Bushell, the escape committee’s, known as the Big X, head, contrived the plans for the mass breakout from Stalag Luft III, Ken Rees was chosen to be part of the digging team. Later on, the WWII vet admitted that he might have been chosen on the basis that he was a Welshman and may have an extent of experience in mining which was not really the case.

The escape plan required the clandestine digging of three tunnels – nicknamed Tom, Dick and Harry – with the third being the longest. Harry was planned to stretch out for as long as 330 feet with its end resting in some woods beyond Stalag Luft’s perimeter wire. Nothing like it was planned before.

Eventually, Tom was discovered; Dick abandoned. And Ken Rees devoted his digging time for the realization of Harry.

The flight lieutenant was a stocky and powerfully built man. His digging time provided him the deviation he needed from the boredom and the hunger he was constantly feeling in prison. It got him through one of last century’s coldest winters. The risk of the tunnel collapsing and being buried under soft sand was constantly hovering over the diggers. Throughout the digging, they experienced several roof falls which they had to shore up through the boards of their prison beds.

Finally, after digging out 250 tons of sand, their great escape was set on the night between the 24th and 25th of March, in 1944. The entrance to Harry was hidden in Hut 104 and all 200 men involved in the plan were gathered there at the appointed time before the guards shut down the huts. They had their escape kits with them.

Ken Rees described that night as stomach-churning, the feeling much worse than what he felt as he waited for a bombing campaign to start. Seeing a German officer among the men in the hut, he was alarmed, though, he discovered later on that it was just a fellow prisoner in a sophisticated disguise.

That night, they executed their plan. However, when the diggers broke out of the surface, they realized that their tunnel did not quite reach the woods they were aiming for. This slowed down their progress causing consequential delays. Eventually, 76 men were able to clamber out into the surface while Ken Rees was crouching low in the tunnel, guiding them. His time to leave came and he was almost at the exit ladder when a shot was fired. That was the signal that the escape had been discovered.

In a rush and in all fours, Ken Rees made his way through the tunnel back to the hut and was the last to clamor up before the tunnel’s trap door was closed. When he got in, he found the other prisoners, burning their forged papers and eating the emergency rations. Only moments after the frenzy, Germans forces arrived.

Ken Rees was promptly sent to the ‘cooler’. There, he heard that 50 of his colleagues were shot by the Gestapo. Along with these 50 men were Roger Bushell and his great friend Johnny Bull.

Ken Rees later pointed out that he would have been one of the 50 men executed had he got out that fateful night. After all, he was a ‘hot sight’ for the Germans given the regular visits he had with the ‘cooler’ and his antagonistic attitude towards the German guards of the prison.

Another escape tunnel was planned later that year, but the fear of getting discovered and shot as well as the fast progress the Allies were having against the Germans factored to the abandonment of the plan.

Late January of 1945 rolled in. It was this time that Ken Rees and the other Stalag Luft prisoners were told to collect their scanty belongings in an hour’s notice and leave the camp. The Soviets were advancing to the east as the Germans made their escape bringing the prisoners with them.

Suffering from severe hardships mixed with a bitter cold weather, the guards commanded Rees and the other prisoners to advance westward. After more than three gruesome months, in May 2 that same year, Ken Rees and the other Stalag Luft prisoners were liberated by the advancing British troops. In no time, Rees was headed to the safety of his home and to his wife, whom he had married just days before he was shot down.

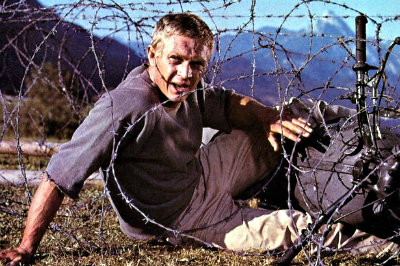

When the WWII vet was told that Steven McQueens’s character in the 1963 American war film The Great Escape was based off of him, he stated that he had nothing to do with that story. He further added that McQueen was a 6-foot tall American while he was a short and stocky Welshman. Aside from that, he did not know how to ride a motorbike. He eventually pointed out that the only similarities he could see with himself and Captain Hilts, McQueen’s character, were that they always annoyed the Germans and were constant visitors of the ‘cooler’.

Ken Rees is survived by his son, also a former RAF officer, and a daughter.

His funeral will be held next Saturday at the Bangor Crematorium.

Goodbye, WWII Flight Lieutenant and The Great Escape hero, Ken Rees!