Necessity, as they say, is the mother of invention, and when the United States faced a pilot shortage in 1942, they freed up male pilots for overseas combat duty by training women to fly military aircraft. Hence, WASP, the Women Airforce Service Pilots, was born.

Despite the usual sexist comments and concerns about women being able to fly in challenging conditions at the time, the women did just fine. More than 1,100 young women signed up to fly every type of military aircraft, including both the B-26 and B-29 bomber.

Their tasks included ferrying planes long distance to and from military bases and departure points. The expectation was that they would see full military service, but instead, they were canceled after two years. The WASP wouldn’t see military status until the 1970s. Then, 65 years overdue, they received the highest civilian honor by the U.S. Congress. Further, President Obama granted the WASP the Congressional Gold Medal in a ceremony on Capitol Hill.

Jacqueline Cochran was the head of the WASP program. She was not only an experienced pilot but a pioneer in the field, who would later go on to be the first woman to break the sound barrier. Her goal was to train women to fly for the army, not just a few dozen that would be integrated into the men’s program.

She wanted the formation of a separate organization with militarization to follow in the wake of her success. In the end, she was successful. The women’s safety records weren’t just comparable, they were often excellent, even surpassing the men doing the same jobs.

The WASP training included nineteen groups of women. First and foremost is the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS) who were an experienced group of pilots, and second, Jacqueline Cochran’s Guinea Pigs – eighteen classes of female pilots. They charged through primary, basic and advanced training courses the same as male Army Air Corps pilots, and plenty went on to specialized flight training.

By 1944, there was a significant amount of controversy regarding women piloting aircraft, and the debate raged about whether it was even required. By the summer of that year, the war was winding down and with it flight training programs, and that meant that the male civilian instructors were losing their jobs, so rather than end up in the common draft they lobbied to take the women’s jobs.

The idea that men could somehow be replaced by women was unthinkable and unacceptable, and so the program was disbanded in December 1944. The final class graduated after training was disbanded. The Lost Last Class, as they were called, served for two and a half weeks before going home on December 20th.

After being told to go home, they went on with their lives, but the former WASP servicewomen were definitely stung by this news. Many of the former WASPs got jobs in aviation, but not for any major airlines, and disappointingly, considering their level of expertise, as airline stewardesses.

However, they didn’t take this lying down, and instead used the fact that the WASP had been forgotten as a uniting force. First, they lobbied Congress to be militarized, even persuading Senator Barry Goldwater to help them. Then, in 1977, as a result of their efforts, the WASP were granted military status.

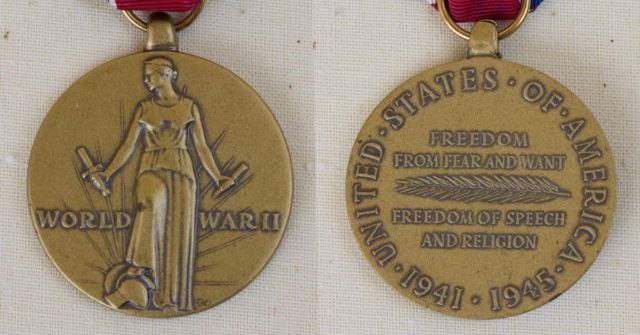

After that, President Jimmy Carter signed legislation indicating that service as a WASP would be considered “active duty” and therefore be subject to all the rules, regulations, and benefits that applied to any other serviceman. Honorable Discharge certificates were henceforth issued in 1979 to former WASP members, and in 1984, each WASP was awarded the World War II Victory Medal.