The D-Day landings on June 6th, 1944 was the Allies attempt to invade Europe and finally push back the Nazi invaders once and for all.

General Dwight Eisenhower, who had been put in overall charge of the invasion, said at the time that there were no alternatives and that it must be a victory for the Allies.

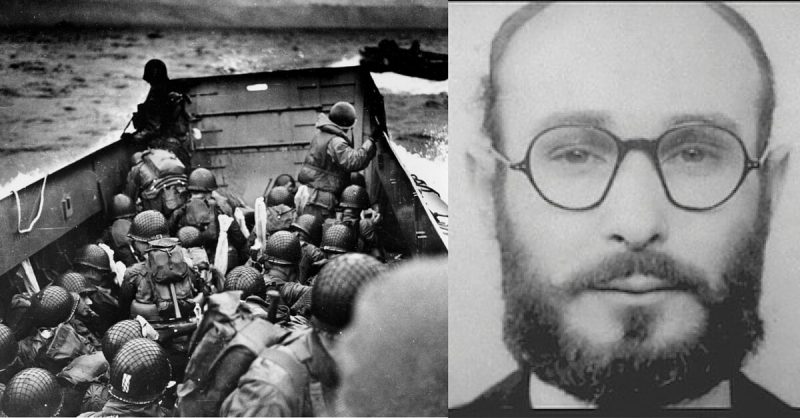

For the first wave of the D-Day landings 6,000 ships sailed across the English Channel to deploy 100,000 troops and 20,000 vehicles onto the beaches of Normandy. During the night thousands of paratroopers were dropped behind the invasion beaches to disrupt German communications, eliminate gun positions, secure important towns and cause mayhem on the Germans.

Around 13,000 planes took part in bombing German positions to help get the men ashore, even though it later turned out that these were mostly ineffective. The airmen were terrified of bombing their own men and delayed the release of the bombs causing some bombs to hit up to 3 miles inland.

It was the largest invasion in military history. However, Eisenhower did have his doubts. In the planning estimates said that the expected casualty rate may reach up to 90% on the first day alone.

Eisenhower became a chain smoker and would puff away dozens of cigarets daily while considering and worrying about the attack. The Allied leaders were also worried, with Churchill saying that he thought it would be a bloodbath and even brash General Patton was ‘restless’ about the invasion. Others were, even more, negative suggesting that the attack could never be a success

Eisenhower wrote a note accepting responsibility and blame should the invasion be a failure and when the final paratroopers took off it is recorded that he cried.

“Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based upon the best information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that Bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone.”

One of the main reasons the Allies were worried was that it had been hard to keep the impending attack a secret. Millions of Allied troops were gathering in the UK in the months before the attack, along with supplies and vehicles. There was no doubt that the Germans and Hitler knew an attack was imminent.

It was the details of the attack that the Nazis could not figure out – the what, where and when. It was this information that the Allies kept top secret, and in the meantime devised a cunning plan to trick the Nazis into thinking that the invasion would take place anywhere but Normandy.

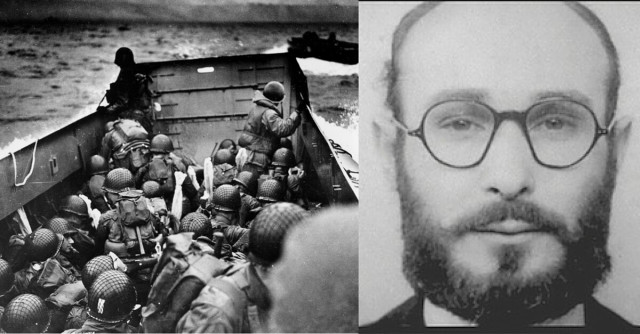

Juan Pujol Garcia, agent Garbo, was a Spanish spy from Barcelona, who worked for the Allies, and he was key to tricking the Nazis. He worked as a double agent; he posed as a Nazi spy working in Britain, but he was really working for the Allies.

The intelligence he produced was largely fictitious but contained enough genuine material to convince the Germans of Pujol’s effectivity. On 8 November 1942, for example, the British and Americans launched a joint invasion of French North Africa called Operation TORCH.

Pujol informed the Abwehr of the attack after it had happened, but the British had postmarked the letter to make it look like he had sent it before. After Operation TORCH, the Germans demanded a faster form of communication, so Pujol “recruited” a radio mechanic.

In cases where Pujol failed to give valuable information, he would claim that the agent responsible had died or was caught. In 1943, for example, a large British fleet set off from the northwest coast of England. To explain why he wasn’t able to report that, Pujol said that his man in Liverpool had died. To support this story, the British created an obituary for the non-existent spy which they published in the local paper.

At the start of 1944, the Abwehr told Pujol that they expected a large-scale invasion of France. They were right, but it was necessary to let them believe it would happen at Pas de Calais instead of at Normandy, where they actually planned to land.

Pujol did such a good job that when the invasion happened on June 6, Hitler was convinced it was a diversion. He therefore held back two armored divisions and 19 infantry divisions at Calais, still believing that the main attack would come from there.

To ensure that no German reinforcements went to Normandy, Pujol sent another report on June 9 giving detailed accounts of a larger unit in England about to attack Calais. He was again believed, so the German divisions at Calais stayed put till August.