On the face of it, it looked to be a rescue mission with little chance of success. Reports had filtered through of the most terrible atrocities committed by the Japanese on American prisoners-of-war. Cabanatuan held the surviving prisoners who surrendered at Corregidor as well as survivors of the Bataan death march – a forced march of 95 kilometers during which approximately 20 000 men had died.

Conditions in the prison camp were dire and the guards were vicious. The American command decided to launch a mission to rescue these prisoners before they were all killed by the Japanese.

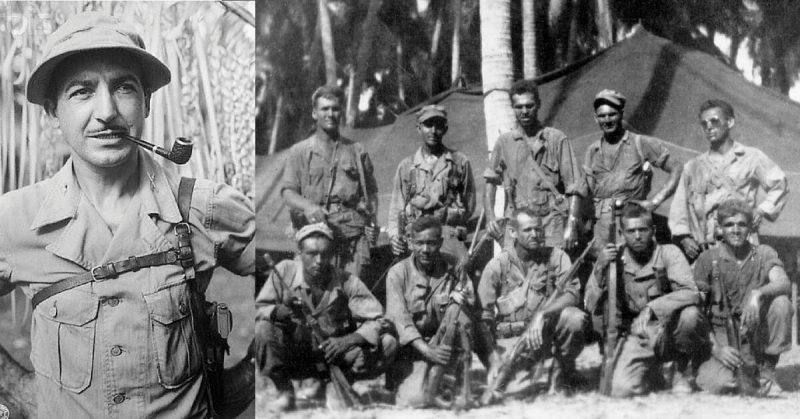

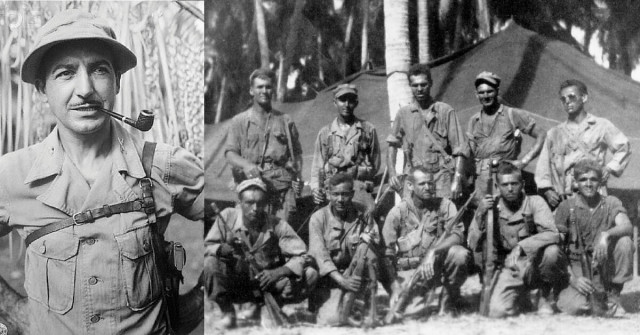

Lt. Col Henry Mucci was placed in charge of the mission – the aim of which was to get the 500 POWs to safety before the end of January 1945. Intense planning and training began at once and Mucci, in the little time available to him, managed to turn 6th Ranger Battalion, reinforced by Alamo Scouts, into a closely-knit commando group. He did not pull punches; he told his Rangers the truth – the mission was more than challenging and extremely dangerous.

The prison was situated 45 kilometers behind Japanese lines and was guarded by over 200 men. Furthermore, it was used periodically as a transit-camp for Japanese soldiers and to add to the danger, not far away was a Japanese base camp, housing thousands more soldiers. To have any chance of success they faced particularly tough training.

“This guy was a true leader,” wrote P. O’Donnell, “It was a daunting task, a true test of leadership. It was amazing how he turned these men into a cohesive unit able to pull off one of the great raids in World War II.” Hampton Sides wrote of Henry Mucci — “they adored him, in large part because anything he asked them to do and anywhere he asked them to go, he was right there alongside them.” Capt. Prince, who would spearhead the assault, said of the men “even knowing the odds were against them living through the ordeal ……… all stepped forward.”

Mucci’s men knew that the Philippine area they were to infiltrate was swarming with Japanese combat troops and that nearer to the prison they would have to traverse 300 meters of open ground. They knew that once they neared the camp, “total surprise, stealth and speed would be crucial.” (W. Breuer.) They would have to nullify the guards, secure the compound, collect the prisoners and get them back to friendly lines. There would be no second chance.

In the darkness of the night of Jan 30, Prince pushed his heavily armed men to the gates of this awful prison. While his men had had to crawl silently and undetected over open ground, a distraction had been provided. Pilots in a P-61 Black Widow flew in such a way as to simulate a distressed aircraft, which engaged the attention of the Japanese.

When Lt. J. Murphy got his men into position at the barracks, where Japanese troops were relaxing, his barrage of fire gave the signal for Prince’s men to attack the gates. The result of this shock, surprise attack was totally successful. The Rangers secured the camp and managed to get the POWs to the meeting place – all in less than an hour.

While the attack had been so successful – the Rangers’ mission would not be fully accomplished until the liberated POWs had been safely delivered to behind friendly lines. Carabo carts, requisitioned from local civilians, were awaiting the POWs at the first stop. The civilians and Filipino guerrillas were essential to the success at this part of the mission, for besides the carts, they supplied food and water and also medical attention along the escape route.

Filipino guerrillas were involved in many skirmishes calculated to keep the Japanese away from the escape route. Civilians supplied yet more food and water as well as extra carts as the prisoners continued along the route. The most dangerous section of the trip was where the column had to cross an open highway in enemy territory.

Roadblocks were established and manned for the hour it took for the long cavalcade of carts and slowly walking men to cross without being discovered. At Talavera the men were transferred to trucks and into ambulances for the last leg to Guimba where they arrived on the 31st January.

Mission Accomplished!

Breuer wrote that on reaching the American post at Guimba, six barefoot POWs handed, “the regimental flag of the U.S. 26th Cavalry, which had fought to the bitter end on Bataan,” to Lt. Gen. Oscar Griswold, who responded, “This is the most touching incident of the war.”

Gen. Barry McCaffrey called the raid “a model for special operations, as well (as)… one of the most remarkable and tactically studied achievements in our Army’s history.”

Dr M. J. King in his commentary on the Cabanatuan Raid writes the following:

The raid was an overwhelming tactical success. It was “an almost perfect example of prior reconnaissance and planning which demonstrated “what patrols can accomplish in enemy territory by following the basic principles of scouting and patrolling, ‘sneaking and peeping,’ [the] use of concealment, reconnaissance of routes from photographs and maps prior to the actual operation, …and the coordination of all arms – all of which contributed to the Rangers’ undetected approach, their gaining complete surprise over the Japanese, the smooth assault on the compound, and their successful liberation of the prisoners. Equally important was the friendly civilian population and the Filipino guerrillas who helped radically with reconnaissance, surveillance, security missions, … route choices and also fought Japanese.

Gen. Douglas MacArthur, who greeted Mucci and his team shortly after the raid, said: “No incident of the campaign in the Pacific has given me such satisfaction as the release of the POWs at Cabanatuan. The mission was brilliantly successful.”

Mucci and Prince both were decorated with the Distinguished Service Cross, for valor.