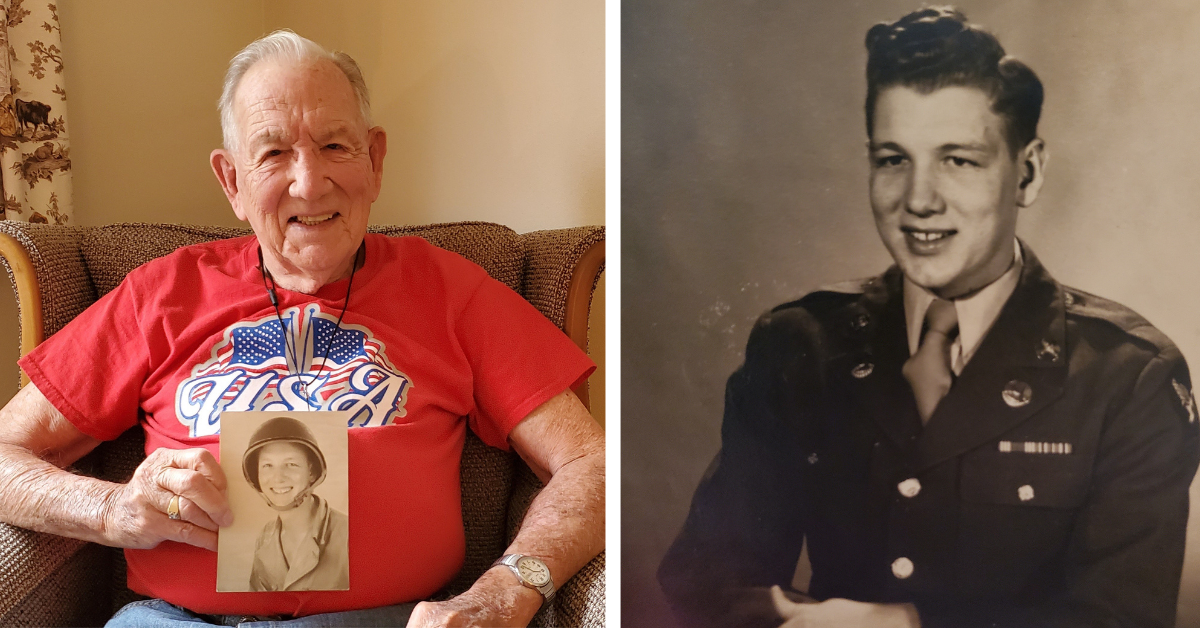

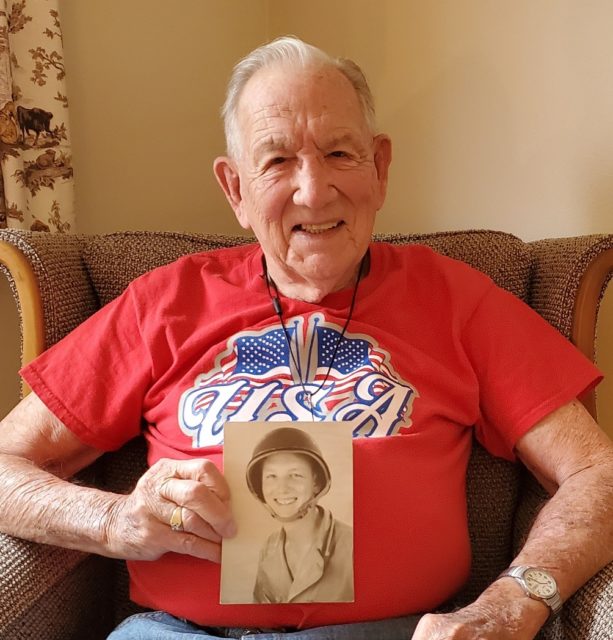

In 1941, after finishing the ninth grade at St. Peter’s Catholic School in Jefferson City, Herb Meyer suspended his education so he could go to work at a local shoe factory to help financially support his family. Yet with the beginnings of the country’s involvement in World War II only months away, he soon joined millions of his fellow citizens who were called to serve in the military in some capacity.

Assigned to Army service

Meyer mirthfully recalled that when going through the induction process, he requested placement with the U.S. Navy; however, during the pre-induction physical, the doctor said he had bad feet and remarked, “I better put you in the Army.”

“I was inducted in May of 1943 and they sent us to Lincoln, Nebraska, for our basic training,” he recalled. “Our training was only supposed to be four weeks, but for some reason, they extended it by two weeks.”

The young soldier wished to become a mechanic during his military service, but since all of the available slots were filled at the time, he was instead sent to a military camp in the Boston area. While there, he spent an additional two weeks in light infantry training before boarding a troopship bound for destinations unknown.

“There were a lot of guys who got seasick, but the troopship stopped at Halifax, Nova Scotia, and we got a pretty good meal there. That,” he continued, “helped make the rest of the trip just a little bit better.”

Another more pleasant factor of the ocean journey was that he did not have to perform kitchen police (KP) duty. As he explained, there were soldiers aboard the ship in custody for being absent without leave (AWOL) who fulfilled these responsibilities.

Meyer’s service in Newfoundland

The final destination, he soon discovered, was Gander, Newfoundland, where Meyer and scores of his fellow soldiers disembarked the ship so that it could continue its journey to Greenland and Iceland. Milling about the docks since they were uncertain where they should report, a colonel with their group made a telephone call to the commanding officer at the nearby airport.

“The commanding officer of the airfield said he needed people and to send us on over, which is just what they did,” said Meyer. “A bunch of us were placed in a guard squadron, and the first thing they had us doing was guarding gas dumps out in the middle of the country.”

The former soldier noted that these fuel depots were situated in remote areas to ensure that in the unexpected circumstance the airfield was bombed, all of the fuel being stored for the aircraft and vehicles would not go up in flames.

Now known as Gander International Airport, the airfield “became the main staging point for the movement of Allied aircraft to Europe during World War II,” explained an article accessible on the airport’s website.

“Gander’s location on the Great Circle Route made it an ideal wartime refueling and maintenance depot for bombers flying overseas,” the article further noted.

He said, “There were other times when we were assigned to pull guard duty around the bombers like the B-17s (Flying Fortress) and B-24s (Liberator) that stopped over on their way to Europe.”

While in the midst of this duty assignment, he was given fifteen days of leave to return to Missouri in 1944 and married his fiancée, the former Dorothy Speckhals. Returning to the airfield in Newfoundland, he was soon given a new duty assignment.

“They moved me over to the billeting office, and I would assign barracks for the pilots and aircrews that had to stay over when either making the flight to Europe or else returning to the United States,” he said.

The end of the war

In 1945, he was given a second 15-day furlough and returned to Jefferson City. While home, the war ended and he received a letter stating that his furlough had been extended by another 15 days. He was then transferred to work in the billeting office at Fort Totten — a former U.S. Army installation located in the borough of Queens in New York City.

“One of the interesting things I recall about New York City is that I got to tour the Empire State Building,” he excitedly recounted. “It was after a small plane had crashed into it and, part of the way up, the elevator stopped and you had to walk to another area to get on a different elevator because the plane had damaged it.”

He disappointingly added, “Once we got to the observation area at the top, you couldn’t see anything because of the fog and clouds.”

The final step of his military experience came on December 13, 1945, when he received his discharge at Scott Field, Illinois (now Scott Air Force Base). Reuniting with his wife in Jefferson City, he returned to work for the International Shoe Company and the couple raised two children in the ensuing years.

Meyer remained employed with the shoe company for nearly 30 years, until the company closed its doors permanently. Shortly thereafter, he was hired by the Missouri Department of Revenue, working for the state until retiring 17 years later.

Maintaining that there are a number of more interesting stories of World War II service than his own, Meyer affirmed that his time in uniform helped him meet several good friends in addition to fulfilling a commitment to his country.

“It was just a situation where Uncle Sam said that he needed people to perform certain jobs and that’s what I did,” the veteran remarked.

“Back then, there wasn’t a question of whether you wanted to go when your number was called…you went because your country said it needed you.”

Jeremy P. Ämick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.