The Battle of Hürtgen Forest for Hill 400 is often overlooked due to its proximity to the Battle of the Bulge. A German stronghold, it provided an observation point overlooking the Roer River Valley, as well as an open view of Allied movements in the area. The U.S. made attempts to gain control over Hill 400 and the surrounding forest, but they failed.

Hürtgen Forest and Hill 400

Hürtgen Forest is located five kilometers east of the Belgian-German border. The 1,312-feet-tall Hill 400 overlooks Schmidt to the southwest and the Roer River Valley to the east, with the town of Bergstein sitting at its base. Its steepest slope is at a 45-degree angle, and the surrounding forest is dense with evergreens.

Along with allowing the Germans to see Allied movements, the location ensured the successful launch of counterattacks. The heavy brush also prevented tanks from climbing the terrain. That, paired with the mines and barbed wire that had been placed throughout the area, made Hill 400 the cornerstone of Germany’s Siegfried Line.

American objectives

By mid-September 1944, the Allied pursuit of the German Army had slowed due to extended supply lines and an increase in resistance. Their next objective was to move up the Rhine River, and it was the American First Army’s task to capture Hürtgen Forest and secure the right flank of the advancing VII Corps.

The Americans were also tasked with attacking a large portion of the German Army’s fixed fortifications along the rear of the Siegfried Line. If they were successful, Hill 400 would provide an excellent observation point over the Roer River.

Preparing to take Hill 400

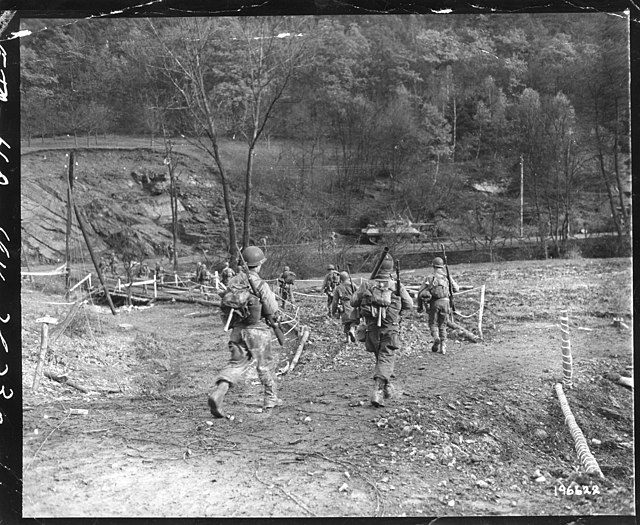

The U.S. 9th Infantry Division made its first offensive move into Hürtgen Forest in September 1944. Unfortunately, by mid-October, they had only gained three kilometers at a cost of 4,500 casualties. A new attack was launched in November by the 28th Infantry Division, but, again, no ground was gained and casualties totaled over 6,000.

A new approach was needed. General Walter Weaver, commander of the 8th Division, asked V Corps commander General Leonard Gerow for Rangers to help in his upcoming assault on Hill 400. The men of the 2nd Ranger Battalion were veterans of D-Day, having landed on Omaha Beach and scaled Pointe-du-Hoc. Gerow released the Rangers and they were trucked to Bergstein.

While on their way to Bergstein, the 2nd Rangers met with a German artillery barrage in the village of Geremeter. They were able to stand up to the attack but were shocked at the scene they’d come upon. The U.S. soldiers before them had not only abandoned their weapons but their wounded comrades as well.

Eventually, the Rangers arrived in Bergstein. They were joined by the 8th Division’s A, B, and C Companies, who took up defensive positions to the south and west of the town, and its D, E and F Companies. By then, Weaver had decided the best course of action was to have the Rangers take charge, so as to keep his infantrymen fresh.

The plan is formulated

Lieutenant Colonel James Rudder devised the plan that would lead the Rangers onto Hill 400. The battalion was divided into three forces, each with its own tasks. D and F Companies were to directly attack the hill, while A, B, and C Companies were to attack and secure Bergstein with the help of a platoon manning 81mm mortars. E Company and tanks with the Combat Command Reserve (CCR), 5th Armored Division were to act as reserves.

Prior to the mission, a scouting party containing members of D and F Companies provided reconnaissance. The information was reviewed by headquarters and passed to the companies, who prepared for the attack. Rangers assigned to the D and F Companies assumed positions in a sunken road near the Catholic Church of Moorish Martyrdom Cemetery.

Just before the mission was to go underway, Rudder was transferred to the 28th Division’s 109th Infantry Regiment. In his place, Captain George S. Williams, promoted to Major, and Captain Harvey Cook were told to head the assault.

The assault begins

At 0730 on December 7, 1944, the assault began. The 65 Rangers of D and F Companies crossed the line of departure and began their attack on the 272nd Volksgrenadier Division. The Germans were quick to assume their positions, despite the surprise barrage. D and F Companies moved forward with fire support from C Company but were targeted by German machine guns and mortar.

The Rangers knew the Germans would immediately counter their assault, given the importance of Hill 400. To prepare, German field marshal Walter Model had offered the 6th Regiment Iron Crosses and a two-week furlough for participating, and they used their higher position to hit the Rangers with a deadly barrage of shrapnel.

Lieutenant Leonard Lomell quickly realized the Rangers were too weak to hold all points along the line and moved to learn where the Germans were building strength. He sent out two-man reconnaissance patrols to check for likely assembly areas and used the information to better dictate the positions of his soldiers.

Battle for key terrain

The first of five German counterattacks occurred at 0930. Using the dense woods to their advantage, German infantrymen rushed the American positions, outnumbering the Rangers. They used burp guns, machine guns, rifles, and potato masher grenades to attack the Rangers swiftly, and the attack soon came to include hand-to-hand combat with bayonets.

The Rangers held their own and forced the Germans to regroup, but the attack wasn’t without its casualties. By noon, two companies had only 32 men, and the commanding officer of D Company had been captured. Despite their losses, the Rangers made do, as Weaver was unable to disengage troops to relieve the battalion.

The second counterattack arrived at mid-afternoon, when 150 German men attacked F Company, outnumbering them 10 to one. The enemy’s efforts were close to paying off when Platoon sergeant Ed Secor charged toward the patrol with two machine pistols he’d acquired from wounded German soldiers. His remaining troops followed suit, and they managed to drive the Germans back.

By 1600, the Rangers were down to 25 men and in desperate need of reinforcements. Unfortunately, Weaver was still unable to send reinforcements, forcing Williams to send 10 men from E Company up the hill. They arrived just in time, as the third counterattack was just beginning.

The heaviest counterattack

December 8, 1944, saw the final two German counterattacks of the two-day offensive. The first came just after dawn, with E Company reporting troops with the German 6th Parachute Regiment attacking the north from Obermaubach. The U.S. troops were able to instigate a German retreat with artillery fire.

The heaviest counterattack came at 1500 hours. Between 100 and 150 German soldiers with self-propelled guns, mortars and artillery attacked the Americans from all sides. Five got within 100 yards of the church being used as a first-aid post, and artillery fell all around. After approximately two or three hours, the Germans were beaten back.

In one final attempt, the Germans tried to slip through the Rangers’ foxholes toward one of the cement bunkers the Americans had overtaken during the assault. They were hit with bursts of BAR and rifle fire, and after 20 minutes were driven off the hill for the fifth and final time.

An Allied failure

By nightfall on December 8, Weaver was able to free up members of the 13th Infantry Regiment and sent them to Hürtgen Forest to relieve the Rangers. After 40 hours of fighting, the Rangers had secured Hill 400, making them the first American unit to do so throughout the four-month battle.

The battle is the longest to have occurred on German soil during World War II, and the longest the U.S. Army has ever fought. Unfortunately for the Allies, the Germans regrouped and launched a new offensive for control of the hill. They were successful, and the Americans were unable to regain control until February 1945.