When the Pearl Harbor attack resulted to USA officially entering WWII, a few of the army’s senior officers contrived to enlist the help of the film industry. What resulted were the finest of Hollywood being able to film WWII most daring and bloodiest combats.

June 4, 1942 at 6:30 AM – John Ford, three-time Oscar-winning Hollywood director, was huddled down on a power station’s concrete roof in the Midway Atoll. This said reef isle was one of the groups of the small North Pacific islands in between Tokyo and the Californian coast.

The 48-year-old director and his crew were armed not with weapons but with 16mm cameras and Kodachrome color film. Ford was going to shoot the action going to take place above the clusters of islands. But then, that action was so unlike anything he had ever filmed in his entire Hollywood career.

Ford kept watch from his position in the tower. being high up gave him an unhampered view of the sea and the islands across from where he was in. A pack of Japanese Zeroes, the Imperial Army’s long-range fighter planes, soon came into view and started to fill the Pacific sky. After first seeing the war planes, he and his team started to roll the cameras they brought. Suddenly, according to the Hollywood director, all hell broke loose.

“planes started falling – some of ours, a lot of Japanese planes. One [Zero] dove, dropped a bomb and tried to pull out, and crashed into the ground,” Ford recounted.

He saw how the Zeroes dived-bombed at targets which included water towers very much like the structure he was in. He was taking footage of the hangar when a Zero dropped a bomb on it from fifty feet. He actually caught on film how the whole structure exploded. Still, another bomb broke through the power station’s corner, its impact blowing Ford off his feet. His camera was running that time. When he regained consciousness some minutes later, the Hollywood director had a shrapnel wound on his arm.

The explosion he experienced could be seen in The Battle of Midway, the film he shot throughout the attack. He lost consciousness after the blast and when he came around after a few minutes, he had sustained a wound due to a shrapnel on his arm.

The last of the tiff between American forces and the Japanese Imperial Army at Midway ended three days later with the former winning what turned out to be WWII’s most critical battle point in the Pacific. For the duration, Ford was able to take into film first-hand accounts of the combat.

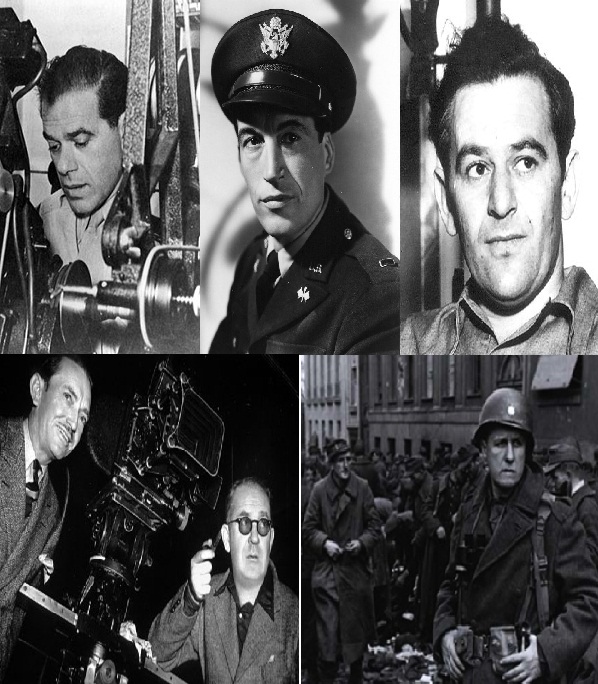

Ford was just one of the several Hollywood directors who were placed “front seat” during WWII just so they could capture the war’s going-ons. America giving a shot on capturing some of the most important campaigns from the time it officially entered WWII after the bombing of the Pearl Harbor was the plan of a few of the army’s senior officers. Before long, it had the band of winning Hollywood directors signed in – Ford, Frank Capra, John Huston, George Stevens and William Wyler. These Hollywood filmmakers had already established reputations of bringing millions of Americans from their homes whenever their movies come out in cinemas and their finished films could move people to tears and laughter, anger and patriotism.

These five Hollywood directors were the most well-known and ingenious in their kind within the American film industry and this standing helped them secure a very important place within the country’s war efforts in WWII.

Getting to Know the Hollywood Hotshots

The enigmatic and aloof John Ford enlisted in the army three months before Pearl Harbor was attacked believing that America’s participation in the war was inevitable. Frank Capra, who at 44 was one of the most successful and richest directors in Hollywood, was also very much ready to serve. He was assigned in the Morale Branch of the army dealing programs regarding the country’s war propaganda and initially made a series of films about why the man in uniform fought meant to be shown to the army’s new trainees and draftees.

“Patriotism? Possibly. But the real reason was that in the game of motion pictures, I had climbed the mountain, planted my flag, and heard the world applaud. And I was bored,” he wrote about his decision to lay off Hollywood for a while and work with the army for the duration of the war.

38-year-old Hollywood director William Wyler, on the other hand, had a more pressing reason to lay his hands on war. A Jewish immigrant from the French-German border region of Alsace, he had several relatives trapped in Europe. His director friend, the 35-year-old Huston who had just outed his first film, The Maltese Falcon to rains of accolades, had a very cocky reason to get himself into WWII – he wanted to revamp himself as a man of action.

Wyler and Huston

Wyler was an officer under Capra’s propaganda unit when he headed off to Europe in 1942. His mind was made up in making a movie about the US Air Force and RAF’s joint missions done over Nazi-occupied France and Germany. In his quest, he found himself 20 miles north from London, in Bassingbourn Field with the worn out crew of the 91st Bomb Group dubbed as the Ragged Irregulars.

Wyler took his flights mostly with the bomber named Memphis Belle and its crew came to respect the Hollywood director’s courage and lack of arrogance. He was willing to go to extremes – at points that even certain young flyers think were out on limb – just to take that good shot he so wanted.

There was one time that Wyler insisted on being placed flat in the B-17’s belly so he could take some shots via the gunner’s ball turret. Had everything went bad and the plane needed to do a rough emergency landing, that decision of being in the plane’s belly would have killed him.

Instead of attending the Academy Awards in 1943, Wyler was in England. His movie, Mrs. Miniver, was leading the pack of nominated films that year with 12 nods including a spot for the best director. That time, he only found out he won an Oscar when a Star and Stripes reporter interviewed him about it a few hours after the ceremony took place.

Huston, on the other hand, was filming Across the Pacific with Humphrey Bogart when he was called for war duty. He had always said that he left Bogart tied to a chair and surrounded by enemy agents and told his replacement “You figure it out” before walking away.

He replaced the shiny lights of Hollywood for a post in the Bering Sea where he was assigned to do a docu-film. Here, he quickly found out that war had a lethal combination of fear and boredom – two factors that really take their toll on one’s nerves.

The first time the Hollywood director rod along in a mission, the bomber had to crash-land on a field still carrying its full load which led its crew including him to evacuate it in haste.

On his second time filming, he was taking shots on a Zero from over a B-24 waist gunner’s shoulder when the Zero fired back killing the soldier he had been with instantly.

Much later in the course of WWII, it was Huston who was also drawn to do the most remorseful and most disreputable episode in the war propaganda history.

When the footage bearing the successful campaign of General Patton on Casablanca got lost at sea after a German torpedo downed it, the army was worried that the first-rate British films might sway the Americans that it was the British who led the Allied effort towards the victory. So, they insisted that Capra take several re-enactment scenes about the said African campaign.

It was Huston who was eventually sent to the Mojave Desert in Southern California and Orlando, Florida – the two places that closely matched North Africa in terms of visuals – with a large band of GIs, a number of dummy tanks as well as P-39 fighter planes. They set up scene after scene of the war planes bombing and strafing the desert as the cameras rolled.

After the filming, Huston was then ordered to fly to London and use the fake footage to to talk the British out of showing their own film about the North African campaign for a more collaborative proposition with the US army. The resulting work would be then entitled Tunisian Victory.

Nevertheless, Huston redeemed himself with his later more authentic works which also had unsettling elements, too.

November 1943 saw Hollywood director Huston in Italy in an attempt to shoot a non-fiction feature about the results brought about by Allied ground campaign. What he found were towns in ruined and the dirty villagers all trembling in fear.

Furthermore, the road out of Naples was strewn with the remains of American soldiers. When he chanced upon Humphrey Bogart, the star of his Maltese falcon film, on a goodwill tour, the two of them spent a sourly long evening filled with booze in a commandeered palazzo.

He returned to New York suffering from a case of insomnia. He recounted the times he would load his service revolver and walk through the Central Park alone in the hopes of getting mugged just so he could shot and kill someone.

Huston was not the only Hollywood director scarred about the events they had seen in Europe. Ford, who was fond of sharing war stories, never talked about D-Day for 20 years.

Hollywood, D-Day and the Liberation

Even Hollywood director George Stevens, who later went on to make Diary of Anne Frank, fell eerily silent about the same events that affected Ford and left three weeks blank in his diary.

The two men were there on the beaches of France in June 1944 to direct a film about D-Day and its impact. The project involved a large group of cameramen and photographers. But what took place that day was rendered them at loss of words to describe it.

“What I’ll never forget is how rough that sea was,” Ford stated in 1964.

“The destroyers rolled terribly. Everybody was stinking, rotten sick. How anyone on the smaller landing craft had enough guts to get out and fight I’ll never understand, but somehow, they did.”

The footage they got that day would not make its debut until after over five decades later. much of it was also blurry and dim or shaky and frenzied.

The footage had shots of wounded men with terrified expressions on their faces, of open-eyed dead soldiers floating on the shallow waters of the beach, of cleaved limbs and of waves tinged with blood lapping on the shore.

Stevens was with the Allies as they moved forward inland arriving in Paris on August 25. The Nazis had just surrendered the city.

The footage he took of Parisian citizens coming out of their homes and shops, crowding the streets weeping and shouting with glee were among the most celebrated images captured Hollywood filmmakers during WWII.

It was Stevens who shot the German surrender inside Montparnasse railway station. However, as he was worried that the poor light in the station would ruin the footage and make it unusable, he ordered the surrendering German general as well as the two Italian generals – General Dietrich von Choltitz and the French generals Leclerc and de Gaulle – to do the act again outside.

He has had a few drinks before the re-shoot and it was said to have barked at General Choltitz these words:

“C’est la guerre, General, c’est la guerre!”

That second take on the handover was the footage shown all over the world.

Stevens had also went to accompany the Allied forces on their march towards Berlin. However, just as the Russians were rolling in from the north, he got orders to proceed to the Dachau concentration camp which was just abandoned by fleeing Nazi troops.

The things he saw there completely changed his life, work and the understanding he had about his own nature.

“It was like wandering around in one of Dante’s infernal visions,” he later recalled.

At loss of what to do, he started rolling his camera at desiccated corpses lying on the train track, inside a boxcar, half-lying in the snow…

He also took footage of skeletal dead men lying on their backs with their eyes up on the grey sky, of the infamous stripped pajamas and the 30,000 barely-living survivors.

Stevens stored all the colored footage he took on his stints overseas during WWII in a North Hollywood storage facility after the war.

They were never shown in public. Even Stevens couldn’t stomach the scenes he had taken into film. He retrieved them only once in 1959 and watched alone in a screening room. However, only after the first minute into the film, he turned the projector off.

Wyler spent WWII’s last days filming aerial footage of the damages done by bombers to Corsica and Rome. He suffered severe hearing loss.

Even though he did his masterpieces, Ben-Hur (1958) and Funny Girl (1968), in later years his hearing never fully returned.

Capra, on the other hand, received a Distinguished Service Medal for his war work. He later filmed It’s a Wonderful Life in 1946. It was praised by movie critics but was a box-office failure. Capra’s career never recovered after it.

Huston went on to win Academy Awards for both writing and directing The Treasure of Sierra Madre. It was his first post-war film which was released in 1948.

He went on to direct about three dozens of films some of which explored the elements of cowardice and bravery. These factored in his movies like The African Queen and The Man Who Would be King.

Ford went on to make many films, too, and even won his fourth Oscars for best director – a record which he still holds – for his work The Quiet Man.

Military life had a significant figure in over half of the movies he made throughout the 20 years after his Navy service. He even talked about doing a dramatic feature about that Pacific War he got involved in.

That dream remained only a dream for the Hollywood director, though, until his death in 1973 at the ripe age of 79.

On his funeral, Ford’s coffin had a threadbare flag draped over it, a memento from the battle of the Midway.