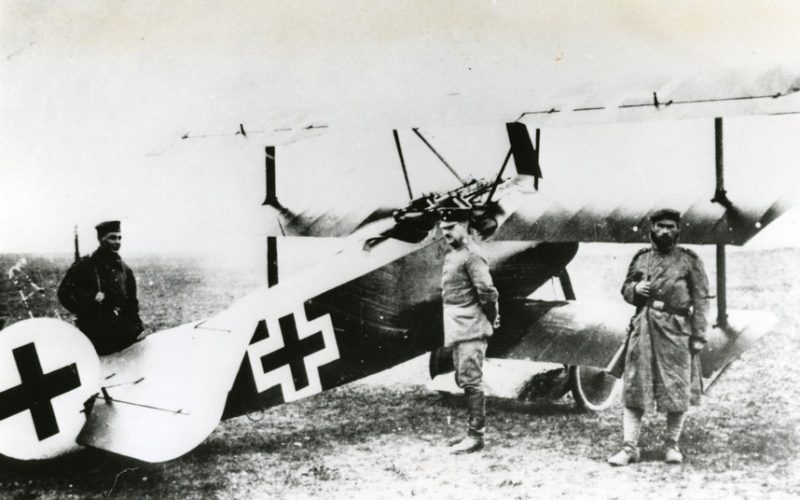

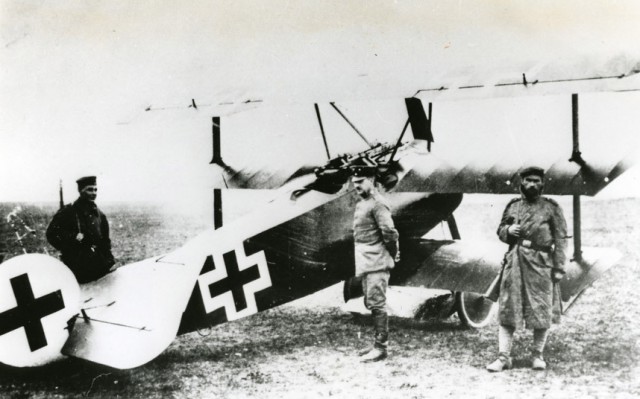

Fighting and dying in a war at 19 years of age is too young. But that was the fate of Lionel Morris, who in September 1916 found himself in a dogfight with Manfred von Richthofen. Morris had little experience as a pilot and he was up against Richthofen, a German pilot who became known as the Red Baron. Captain Tom Rees was Morris’s fellow crewman in the observer position located at the front of the British F E 2b aircraft. Sadly, he died as well. 2nd Lieutenant Morris was able to land the plane but eventually died from the severe injuries he sustained.

This deadly encounter was just the first of Richthofen’s storied war career. He is credited with a whopping 80 aerial combat victories.

It is amazing to think that just months earlier Morris had been a student at Whitgift School in Croydon, England. This year, his alma mater is telling his story through an exhibition – Remembering 1916: Life on the Western Front. Headmaster and exhibition director Dr. Christopher Barnett believes that 1916 is arguably the most fascinating year of World War I.

Battles such as Verdun and the Somme on the Western front and the Battle of Jutland in the North Sea were memorable and important. That was the year that the warring sides came to realize that this global battle was not going to end anytime soon.

Whitgift School commissioned a painting by aviation artist Alex Hamilton to display in the exhibition. It is intended to demonstrate a battle in the air near French the town of Cambrai that involved Morris.

Barnett explained how von Richthofen shot down Morris’s plane before landing next to it. German leaders took great pride in the Red Baron’s work. They asked a researcher named Zapryan Dumbalski to write a short autobiography on him, a copy of which is featured in the exhibition as well.

War Posters

The exhibition also displays many propaganda posters from that time period. Barnett aimed for a shared history that focuses on the losses and experiences of the British, the Germans and the French. The posters are derived from all three countries, to show how each government tried to motivate their home population to help in the national war effort.

The United Kingdom did not implement conscription until the spring of 1916. Prior to that time, the armed forces relied mainly on volunteers. Authorities in Britain used different approaches such as stirring quotes from Lord Kitchener, calls to avenge German invasions of Belgium (a neutral country), and pressure to do right by veteran soldiers who had valiantly fought in previous wars. The British strategy was to play on the emotions; many men like Morris were motivated to join the war because of such campaigns.

By displaying the posters together as a group despite coming from different countries, the character of each country really comes through. The different approaches to accomplish similar goals strongly highlights the individual countries’ sentiments and cultures.

For example, Germany and France did not have to emphasize the need for volunteers to join the armed forces because conscription was already implemented. However, there was always a need for money, and these posters called for donations. The French posters encouraged people to fund the 2nd National Defense Loan, and one German poster said, “Help us win! – subscribe to the war loan.”

Battle of Verdun

The town of Verdun was a highly contested area that the French and Germans fought over for ten full months in 1916. It was located on the Western front just east of Paris, and the battle that raged there was the longest of the war. The German principal strategist Gen Erich von Falkenhayn planned the battle with the hopes of tiring out the French army. By his calculations, this would compromise the British and Russian alliance. Once the battle ended, 800,000 soldiers were dead, wounded or missing.

In a display of the image “Barbed Wire” by Dutch artist Louis Raemaekers, the horror of trench warfare are

depicted at the Whitgift School exhibition. The Dutch government found Raemaekers’ cartoons to be quite political, and critical of the German actions. According to Dumbalski, this was concerning to a government that was trying to remain neutral.

This led to Raemaekers’ relocation to London with his family in 1916. It was only then, in the same year, that he published a book with some controversial cartoons. Despite being a private individual with no military role, this artist had an impact on World War I.

Lost Lives

Most importantly, the exhibition displays a number of artifacts from that time that have a crucial historical value, says Barnett. They help make that era less abstract for those of us trying to envision 100 years ago.

The kit and weapons administered to soldiers were not up to the challenge of modern warfare, according to Dumbalski. On display are German trench clubs, which had a medieval look to them. Essentially, they could only cause damage within a very close range of the enemy.

One image on display depicts a British pillowcase gas mask and rattle. Dumbalski explains that gas usually killed people in the long term. It was such a deadly weapon, but it was invisible. This is why it served as one of the terrifying aspects of the war for soldiers.

In this same year there was the introduction of the Brodie helmet. British servicemen wore the domed headgear while fighting on the Western front. The exhibition also displays a rare type that shows the Tower of London. Germans experienced a switch in gear in 1916, as they went from using the leather Pickelhaube helmet to the bell-like Stahlhelm. Germans continued with the distinctive steel dome feature until World War II.

Some of the items on display are extremely personal. There are some letters written between soldiers and their loved ones back home, as well as a shipping chest that carried the soldiers presents from home.

The final section of the exhibition is dedicated to the 251 former Whitgift students and masters who died in World War I.

An extract from ‘Wind on the Downs’ by Marian Allen was the poem chosen to set the mood for this final section:

I like to think of you as brown and tall,

As strong and living as you used to be,

In khaki tunic, Sam Brown belt and all,

And standing there and laughing down at me.

Because they tell me, dear, that you are dead,

Because I can no longer see your face,

You have not died, it is not true, instead

You seek adventure some other place.

Leave a Comment