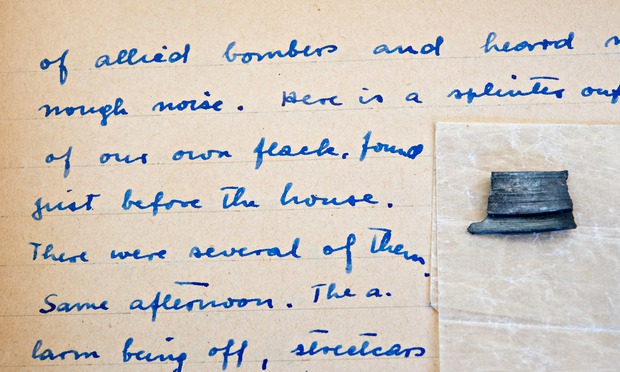

On March 26, 1944, Maria Madi wrote that she “was going to be a witness.” Her handwritten 16 volume diary is just that as it provides a grim portrait of life in Budapest during the desperate and horrific last days of World War II.

As a divorced doctor with a daughter and a grandchild living in America, she began her diary in December 1941 as personal correspondence to her daughter Hilda. As time went on, it became less of a personal letter than a chronicle of the agony faced by Hungarian Jews under the Nazis. By the Fall of 1944, she took on tremendous personal risk by hiding her Jewish friend, Irene Lakos, along with her friend’s seven year old nephew named Alfred.

As her first entry describes, she had given up hope of emigrating to the United States as her daughter had successfully done two years before upon her marriage to an American.

She considers the Hungarian leadership during this tumultuous period as “stupid.” Hungary had developed closer ties to the Axis powers as it benefited from close relations with Germany and Italy to escape the effects of the Great Depression and to expand its borders.

Although reluctant, Hungary did join the Axis powers and participated with Germany on the disastrous invasion of the Soviet Union, losing some 100,000 soldiers.

Given the equivocation of the Hungarian leaders and their attempts at behind the scenes negotiations with the Allied Powers, Hitler took steps to take full control of Hungary. By 1944, with the appointment of a compliant prime Minister, Dome Sztojay, Hungary was reduced to a protectorate of Nazi Germany.

Maria Madi’s entry of March 30, 1944 reflects these events by writing,

“The German propaganda on the Hungarian radio told us that Hungary has decided its fate, to hold by the side of Germany and against Bolshevism. They did not ask me or any of my friends or acquaintances. Pray, who was it who made the decision.”

With the invasion of the Nazis came, Albert Eichmann personally supervised the Holocaust of Jews in Budapest. For the Jews, Hungary had been a place of relative sanctuary. In fact, many Jews had moved to Budapest to escape the oppression occurring earlier in the war in other countries.

Under this reign of terror, deportations to death camps in Poland began in earnest. One third of the Jews killed in Auschwitz were Hungarian citizens. In total, some 600,000 Hungarian Jews perished.

In her entry for April 20, 1944, she describes how, “Every day a new cruelty. Last night 250 Jews and Jewesses were called to work with a rug and a pail and it is believed they will have to work and live close to the targeted areas.”

On September 18, 1944, she laments the passing of a democratic Hungary: “after a few months of German propaganda all our rights are swept away like a building on the sand…”

On October 17, she arrived in her apartment to find her friend and her nephew there. For four long months she sheltered them. The boys’ father was deported to a labour camp and escaped and survived the war. His mother, Rosza, was killed at Auschwitz.

Upon the withdrawal of the Germans from Hungary in February 1945, her diary notes Alfred’s father’s return, pleased to find his sister and son safe, The Guardian reports.

The family moved to United States where Alfred, now 77, lives in Waleska, Georgia.

Mari Madi also managed to emigrate to the United States after the war where she worked as a psychiatrist. She passed away in Houston in 1970 at the age of 72.