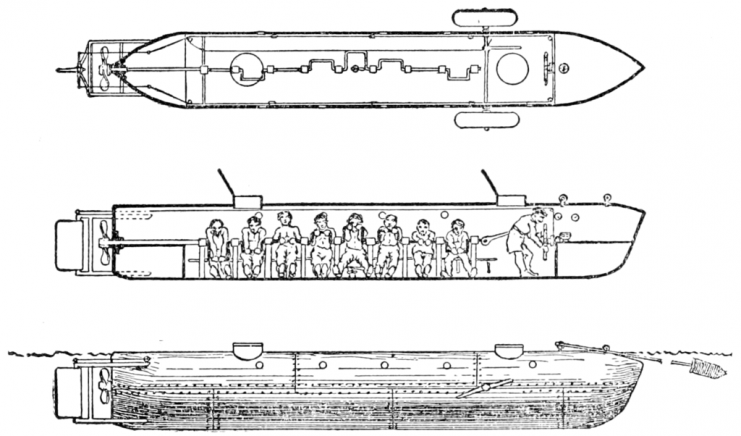

During the Civil War, the Confederacy had a submarine called the H.L Hunley. It was 40-feet long (or twelve meters), bulletproof and built in Mobile, Alabama. It’s propulsion system consisted of seven men cranking a giant screw.

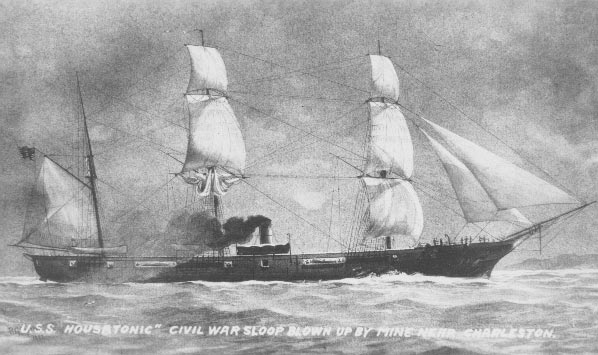

Naturally, it wasn’t what anyone would consider a safe workplace as between July 1863 and February of 1864, the sub sank three times, killed twenty-one of its own crewman. But even such, it did manage to make history because on February 17th of 1864, the Hunley rammed a live torpedo into the hull of the USS Housatonic, effectively becoming the first submarine to sink an enemy ship.

Sure, the Hunley sank as well, killing its entire complement of eight crewmen – a high price for making history.

What has never exactly been clear is just why the Hunley sank. But on July 18th, marine archaeologists from South Carolina’s Clemson University revealed a clue to the Hunley story. Researchers discovered a hidden fail-safe mechanism located in the Hunley’s keel that should have helped the crew facilitate an emergency escape.

Involved were a series of heavy metal slabs known as “keel blocks,” each of which weighed close to 1,000 pounds (or 454 kilograms). These were supposed to be released from the sub with the pull of a lever. Instead, they weren’t.

Michael Scafuri, a marine archaeologist at Clemson University who has made a career of studying the Hunley, stated that the keel blocks were not released, and instead were still perfectly locked in place, and for whatever reason the Hunley’s crew did not try to escape the ocean floor. Scafuri told the Associated Press that it was evidence that no one had panicked on board.

This relates to the theory that the final crewman of the Hunley were either blindsided, or otherwise resigned to their fates. Previous investigations of the Hunley discovered the bones of all eight crew members still holding their posts, producing evidence that there was otherwise no panic in the ranks.

Another hypothesis, this one proposed by researchers from Duke University, suggests that the crew of the Hunley accidentally killed themselves through exposure to the shock-waves of a nearby torpedo detonation.

The researchers produced a scale reproduction of the explosion using model ships, and therefore illustrated the suggestion that resulting shock-waves from the torpedo blast would have been sufficiently powerful enough to burst the blood vessels in the crewmen’s brains and lungs, and at the very least would have definitely rendered the crew incapacitated, if they weren’t killed directly.

The discovery of the Hunley came approximately 4 miles (or 6.4 kilometers) off the coast of Charleston, South Carolina, in 1995, and wasn’t effectively raised from the harbour until 2000. In the past eighteen years, conservators scoured away more than 1,200 pounds of the natural overgrowth of silt, sand and sea life called “concretion” from the ship.

Yet, as scientists keep scouring away the concretion and revealing more of the sub’s interior, there is the suggestion that more answers about the mystery of the Hunley’s final voyage are likely to be revealed.

“We keep seeing parts that no one has seen in 150 years,” Scafuri told the AP. “All of them add into the mix of what happened and how this sub was operated.”

Scafuri has also stated that they have uncovered a number of artifacts, and managed to produce reconstructions of the faces of the crew members, as well as gaining more knowledge regarding the science behind the submarine.

One of these artifacts is Dixon’s coin. As legend would have it, Hunley Captain George Dixon’s sweetheart gave him a$20 gold coin when he left for war. The coin saved his life during the Battle of Shiloh, when a bullet struck the coin in his trouser pocket.

Are you a fan of all things ships and submarines? If so, subscribe to our Daily Warships newsletter!

During the excavation of the Hunley, a gold coin minted in 1860 was uncovered lying on Dixon’s hip bone, warped irrevocably by the impact of a bullet. One side bears the image of Lady Liberty, while the other side has been sanded, and re-inscribed with the following: Shiloh, April 6th 1862, My life Preserver, G.E.D.