Can you imagine what it must be like to be marched out to face a firing squad, say goodbye to your closest friend who is standing next to you and then have the squad shoulder their rifles and march away having not fired a shot? What are the odds on that happening during a war situation?

The mind boggles at the odds of this happening but this did happen to Charles Rodaway who served in the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment during World War II.

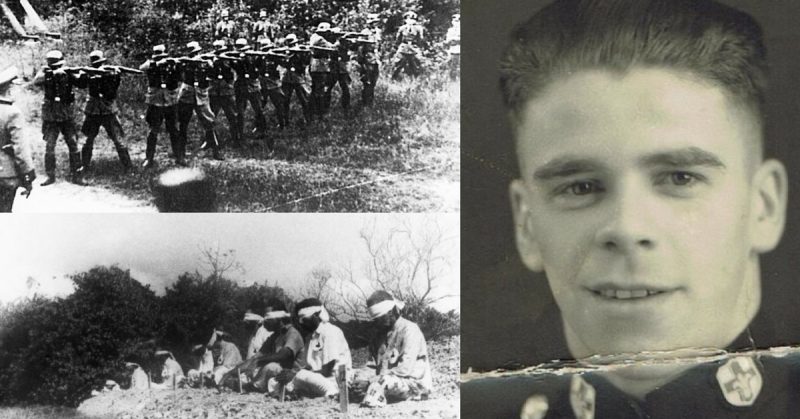

At the age of 12, Charles walked from Blackpool to Fleetwood, a distance of seven miles, to join the Territorial Army. Six years later, at the legal age for active service, he joined the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment and was posted to Shanghai in 1934. He undertook guard duties in Shanghai before being transferred to Singapore in 1938. At the fall of Singapore in 1942, he was captured by the Japanese and put to work as a labourer in the Kawasaki shipyards, near Tokyo. In 1944, he and a friend attempted to escape but were captured and sentenced to death by firing squad for the escape attempt.

At the fall of Singapore in 1942, he was captured by the Japanese and put to work as a labourer in the Kawasaki shipyards, near Tokyo. In 1944, he and a friend attempted to escape but were captured and sentenced to death by firing squad for the escape attempt.

Media reports in England indicated that he had been shot but at the end of the war when Charles returned home it was evident that he had had a miraculous escape. In an interview, he said, “I said to my pal, ‘This is it’. Instead of a volley of bullets, the officer in charge, ordered the firing squad to shoulder arms and marched them away.

He and eight other POW’s were sentenced to 15 years incarceration at Sakai Prison in Osaka. In a 2005 interview, he told of the horrendous conditions in the prison:

“There was no heat or fan; no water, a wooden pail for a toilet, one light hung from the ceiling, a small barred window at the rear of the cell. Clothing was one thin shirt, one thin trousers, no shoes or socks, no jacket or kimono. No wooden box, only the floor to sit on. Only one thin blanket for cover. Bathing was usually allowed once a month; no soap, no washcloth or towel, no clean clothing.”

Charles was released from the prison, a week after the Japanese surrender, when it was liberated by Allied Forces in August 1945. His family were stunned when he reappeared in Blackpool. They had waited at the train station for him, and when he did not appear they were convinced that he had died.

In 1948, he emigrated to Canada but made many trips back to his hometown until he became too old to travel. On the 12th March, he celebrates his 100th birthday. His wife, Sheila, said “It’s quite an accomplishment, especially considering the inhumane conditions during his time in Japan prisons. He’s absolutely amazed he’s lived so long, and feels wonderful, excitedly looking forward to his birthday although he can’t quite believe it! He credits truthfulness and honesty as the key.”

An amateur historian, Tony Rodaway, who is no relation to Charles is credited with bringing this story to the attention of the world. Most soldiers, on their return from war, do not talk about their experiences as it is often much too painful. In Charles’s case he must give thanks every day that the firing squad were called away but the nightmare of coming that close to being executed must have plagued him for a very long time.