John Billings is a former military pilot who worked for the Office of Strategic Services (the precursor to the CIA) during World War II.

In February of 1945, he accepted what was expected to be a suicide mission. It was so dangerous, the Royal Air Force declined to take it. But Billings agreed to fly into the Alps behind enemy lines and drop a group of operatives on a frozen lake.

The mission was a success, and the Allies received critical information about Nazi military movements during the final part of the war.

On March 21, 2018, the OSS was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal – the highest civilian honor the US Congress can grant. Billings was among 20 OSS veterans at the ceremony which was also attended by House Speaker Paul Ryan, R-Wis. And Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky.

Since 2013, advocates have been seeking Congressional recognition of the role the OSS played in US intelligence operations. A bill was introduced in 2013 but stalled for several years in the House of Representatives. In 2015, the bill was re-introduced, and this time it passed in 2016.

It is believed that there are still 100 to 200 veterans of the OSS still living out of the 13,000 civilians and service members that were employed by the organization.

Billings expressed his appreciation for being recognized, but the feeling was bittersweet. “So many people, deserving people, are not here anymore. It would have been nice to have them know about it, as well,” Billings said.

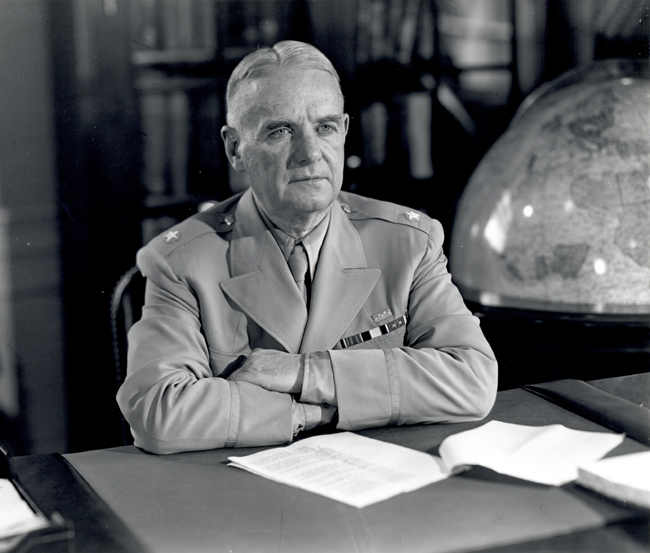

William “Wild Bill” Donovan founded the OSS in 1942. Donovan was a politician and a veteran who served with distinction in World War I.

The OSS had a mission to help the US improve its intelligence operations in the face of the Axis war efforts. By the time it was dissolved in 1945, it had hired thousands of research analysts and sent covert operatives overseas.

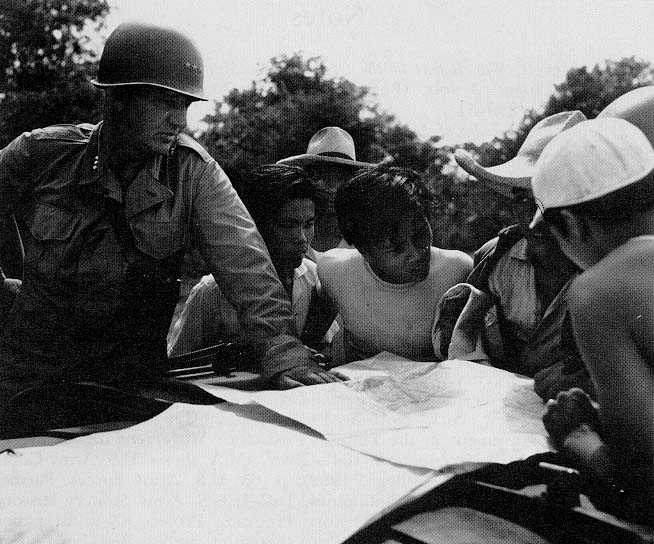

Some of the operations that the OSS was involved in included parachuting operatives into France in order to support the D-Day invasion in Normandy and working with the Kachin tribe in what is now known as Burma to collect information on the Japanese forces.

During the ceremony, Rep. Marcy Kaptur, D-Oh., remembered her own uncle, Cpl. Anthony Rogowski from Toledo. She shared portions of censored letters she had received from him that described the “pure hell” he lived in as he guided military assets across mountainous roads in a secret Asian location.

Marion Frieswyk worked for the OSS with her future husband, Henry. They were chosen by geographer Arthur Robinson who noticed their work in a summer post-grad class. The two moved to Washington to build maps and topological models for the military and political leaders. When the OSS closed, the two joined the CIA. Marion left in the 50s. Henry stayed on as the head of the cartography division until he retired in 1980.

Marion said the work was very secretive. Their own children had no idea where they worked.

CIA spokeswoman Heather Fritz Horniak delivered a statement that commended the officers of the OSS and stated that “the officers of the CIA are proud to follow in their footsteps.”

The branches of the OSS family tree include not only the CIA but the military Special Operations Command (SOCOM) and the State Department’s intelligence bureau.

Charles Pinck of the OSS Society, an organization that seeks to promote the achievements of the OSS and honor members of the intelligence profession, said that it took 75 years for the OSS to receive recognition from Washington. He noted that Donovan once said he had greater enemies in the nation’s capital than Hitler had in Europe. Pinck’s father served with the OSS, working in China, behind enemy lines.