1. Sanitary Pads

Cellucotton was already discovered before WWI broke out by a small US company named Kimberly-Clark. James C. Kimberley, the firm’s vice-president along with the head researcher Ernest Mahler discovered the material – which was five times more absorbent compared to cotton but was less expensive when mass produced – while on a tour in pulp and paper plants in Germany. They brought the said material to America and trademarked it.

When America officially entered the Great War in 1917, Kimberley-Clark started to mass-produce the padding with the intent of using it for surgical dressing. The production was at a rate of 380-500 feet every minute.

However, it was how Red Cross nurses assigned in the battlefields used these wadding for their own personal hygiene, seemingly innocent invention, that brought great fortune to the once small firm.

The end of the Great War brought a temporary suspension to K-C’s wadding business since its main customers – the Red Cross nurses and the army – no longer needed it. They repurchased the surplus from the army and went on to forge a new direction for the invention they introduced. After much deliberation and tests which lasted for about two years, Kimberley-Clark released the first ever sanitary napkin made up of Cellucotton and fine gauze. The first work was done in a small wooden shed in Neenah, Wisconsin with female workers doing making of the napkins by hand.

Kimberley-Clark’s new invention, the sanitary napkins, were branded Kotex which stood for “cotton texture” and became available to the public October of 1920, only two years short after the Armistice.

2. Facial Tissues/Paper Handkerchiefs

Nevertheless, Kimberley-Clark’s sanitary napkin business wasn’t so successful at first. This was in part because women found it hateful to buy the said product from male shop assistants. The company pushed the idea to many shops about allowing anonymous buying of the product, allowing women to get it on their own and just leave money for payment in a box.

Sales of Kotex did rise but not fast enough for K-C so the firm eventually had to look at other avenues for the invention.

The break came when CA “Bert” Fourness brought forth the idea of ironing the cellulose material resulting to a softly smooth tissue. After a series of experiments, facial tissue was born and released in 1924. The invention was trademarked as Kleenex.

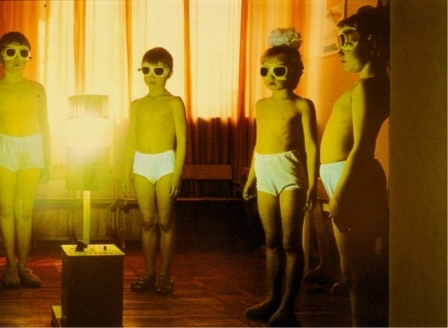

3. Sun Lamps

Roughly half of the children’s population in Berlin suffered from rickets – a health problem which results to bones becoming soft and malformed – during the winter months of 1918. During that time, the cause for the sickness was still unknown though medical officers connected it to poverty.

Kurt Huldschinsky, one of the doctors in the city, observed that all of his patients who suffered from rickets were pale. So, he decided to experiment on four of his patients. A three-year-old child named Arthur was included in his experimentation. He placed his four subjects under the light emitted by mercury-quartz lamps which gave off ultraviolet light and recorded his observations.

Throughout the treatment, he noticed that his young patients’ bones started to get stronger. When summer rolled in (May of 1919), he had his four subjects sit in the terrace basking under the sun’s heat. The result of Dr. Huldschinsky’s experiments was met with keen interest when it was published. Later on, doctors found out that vitamin D is needed to build up stronger bones with calcium and that the process of bone strengthening is put into action via ultraviolet light.

The doctor’s findings led to the invention of sun lamps.

4. Daylight Saving Time

Putting clocks forward during spring and setting it backward during autumn was already pushed forward even before the Great War broke out. In a letter to the Journal of Paris dated 1784, Benjamin Franklin put forward the idea. His reasons: candles got wasted on summer evenings because humans stayed up later than the sun while the goodness of the sunshine got wasted at the start of the day since humans stay too long in their beds to bask in it.

Proposals identical to what Mr. Franklin proposed were made in New Zealand and UK in 1895 and 1909 respectively though both did not yield concrete results.

The advent of WWI started the dawn of the Daylight Saving Time invention. On April 30, 1916, Germany, faced with a coal shortage, decreed that clocks should be moved forward an hour forward to give an extra hour of daylight in the evening. It was the country’s way of saving coal and light. However, other countries immediately adapted it.

Britain started a mandate similar to Germany’s three weeks after the latter did – on May 21, 1916. Other European countries followed suit. Come March 19, 1918, the American Congress went on to form several time zones and declared daylight saving official two days later until after WWI ended.

Practicing Daylight Saving Time was discarded at the end of the Great War but the invention had already rooted that its practice was eventually revived.

5. Tea Bags

Tea bags was not an invention to remedy some wartime difficulty. Common stories have it that an American merchant started the practice of putting tea in small packets or “bags” and sent them to his customers. By any means the bags was dropped into water and viola! the rest of the story is history, as the tea industry states.

However, it was a German company named Teekane that copied the idea of the accidental invention. The firm supplied tea to troops placed inside small cotton bags. The invention was labeled at that time tea bombs.

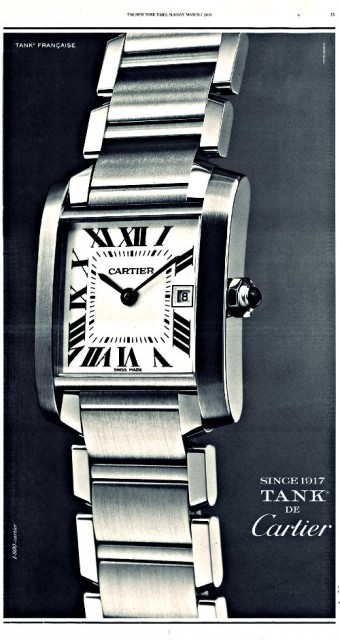

6. Wristwatch

Wristwatches were not a Great War invention. But their use became popular during and after the war until now. After WWI ended, they became the norm when it comes to telling time.

Pocket watches were the “in” thing when it came to men. It was high fashion for men to attach their watches in chains and just get them from their pockets and flip them open if they wanted to know the time. Women, on the other hand, were the ground breakers as far as the wristwatch invention is concerned. Elizabeth I, for one, had a small watch strapped on her arm.

Mappin and Webb were said to come up with a watch fitted with hole and handles for strapping during the Boer War and bragged about how it was so useful during the Battle of Omdurman. In spite of these early developments, it was in the WWI that the the use of the wristwatch invention legitimized all thanks to war’s vital need for time synchronization.

Ground soldiers needed watches but it was also vital to have their two hands free and ready for battle. Same went for the aviators who had to have two hands free when controlling their war planes but vitally needed watches. So, the wristwatch was handier than the pocket watch.

As a matter of fact, the iconic Cartier’s Tank Watch was a WWI invention that Louis Cartier, the French watchmaker, made to celebrate the new Renault tanks he saw in 1917.

7. Vegan Sausages

No, soy sausages were not a hippy invention. They were an idea from the inventive mind Konrad Adenauer, the man who became the first German chancellor after WWII ended.

During WWI, Adenauer, then a mayor in Cologne, thought of ways on how to substitute scarce materials with what was abundantly available in the countryside. Germany at that time was already feeling the sting brought about by the British blockade. At first, he made bread using a mixture of rice-flour, Romanian corn-flour and barley instead of wheat which was on shortage. That worked until Romania entered the Great War and the its corn supply dried up.

From the bread he made, he searched for a new approach on making sausage and ended up with a food invention that was dubbed Friedenswurst or the peace sausage – a sausage using soy instead of meat. He tried applying for a patent for his the sausages in Germany’s Imperial Patent Office but was denied. The office did not consider the invention sausage as did not contain any meat.

Surprisingly, the Cologne mayor had more luck in Britain – Germany’s enemy during that time – when King George V gave him the copyright for his soy sausage invention.

The soy sausages were not the only ones Adenauer invented in his lifetime. But, the meatless sausages were his lasting contribution to humankind.

8. Zippers

People have long searched for ways in keeping the cold out – hooks, clasps, eyes and a combination of all have been tried throughout the centuries in search of convenient ways to fasten clothes together.

However, one Swedish-born US emigrant named Gideon Sundback who put an end to all these “searching ways” with his invention – the zipper.

When Sundback became the head designer at the Universal Fastener Company, he concocted the Hookless Fastener, the first ever zipper with its slider that locked two sets of teeth together. When WWI broke out, the US army, particularly the Navy, used them for the soldiers’ uniforms, and boots. After the war, the practice of putting the said invention into anything that needed them followed suit.

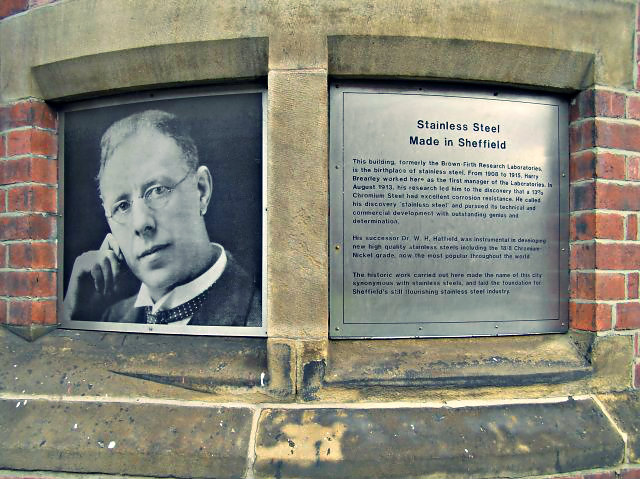

9. Stainless Steel

It was Harry Brearley of Sheffield who discovered stainless steel so the invention is credited to him. That fact is proudly etched in the city’s archives with the year of the discovery being put as 1913.

The story behind the invention is this: the British military, in its quest to find a better metal for guns, asked Brearley, a metallurgist at a company in Sheffield, to find harder alloys.

He experimented on adding chromium to steel. Over the course of time, he threw several of his experimentation into the scrap heap thinking of them as failures. However, he noticed that the ones he threw away as scraps had not rusted. That was when he knew he had uncovered something significant – steel that did not rust.

During WWI, the invention was used in a number of plane engines. Over time, its use extended into the household as dinner wares and of course, in the medical instruments that hospitals strongly depend on.

10. Pilot Communications

Before the Great war broke out, there were no means available which allowed pilots to talk to those who were on the ground. At the beginning of WWI, communications among units depended heavily on cables which tanks or artillery easily cut off. Germans also found a way of getting into the communication cables of the British.

There were other means for communicating during the war – the use of runners, pigeons, flags, dispatch riders and lamps – but all seemed deficient. Aviators, on the other hand, relied on hand gestures and shouting. Clearly, something had to be done to remedy the problem and the solution pinpointed was going wireless.

Radio technology was already an existing invention it but needed to be developed. Its major advancement came at Brooklands and later at Biggin Hill during the First World War.

In the book British Radio Valves: The Vintage Years – 1904-1925, author and historical research specialist Keith Thrower stated that the big steps were taken in 1916. He wrote that earlier bids for putting radios in aviation crafts were hampered by the noise coming out of the planes’ engines. To alleviate this, the invention of the helmet with built-in microphones and earphones came into being.

After the Great War ended, the invention took off to civil aviation.

Source: BBC News