The Cold War was infamous as a time of bizarre weapons, vehicles, and projects. Because the US and the Soviet Union were not fighting a conventional war, they had to get extra creative in order to gain an upper hand over their opponent. The secrecy of those projects required both sides to spend huge amounts of money to find out what each side was developing. When a Soviet submarine carrying nuclear missiles mysteriously sank in 1968, the US saw the event as a perfect opportunity to grab a glimpse at Soviet nuclear weapons technology.

K-129

By 1968, the Soviet submarine K-129 was by no means new, having been launched almost a decade earlier in 1959. The diesel-electric-powered Golf II–class submarine was part of the Soviet Pacific Fleet. She received upgrades to modernize her in 1964, returning to service in 1967.

With these upgrades, she now carried some of the Soviet’s latest electronics and was armed with the latest submarine-launched nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles, the R-21. These were the first missiles fielded by the Soviets that could be launched underwater, making her a valuable target for US intelligence, not that they knew it yet.

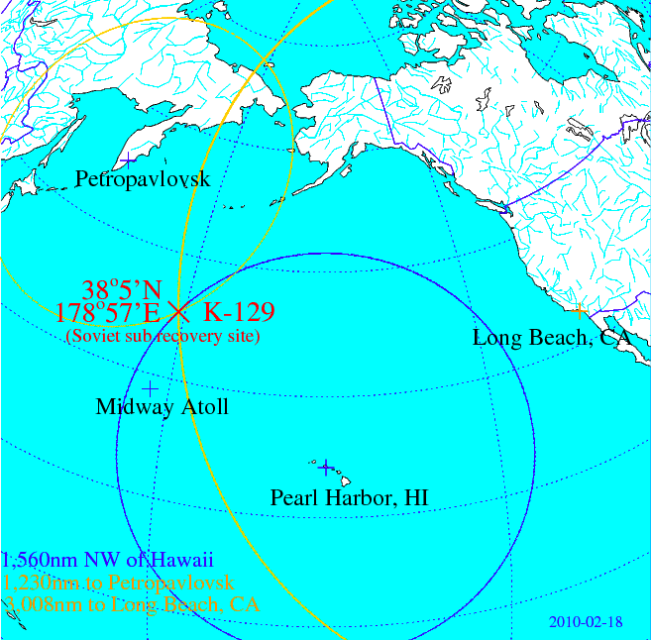

K-129 started a new patrol in February 1968, which would last until May 5. However, by early March she had missed her scheduled radio check-ins, which alarmed Soviet naval headquarters. She had still not made contact with her headquarters by the third week of March, prompting the Soviets to declare her missing while launching a full-scale search and rescue operation to retrieve their nuclear-armed submarine.

Almost 40 vessels and 53 aircraft hunted for K-129 for two months, using all means possible. They used their sonars at full power, and even tried to make contact with K-129 on open channels. The search was eventually called off, after nearly 300 flights and combating 45 feet high swells.

The US was watching closely

All of this commotion in the Pacific Ocean naturally caught the attention of the US, who quickly deduced that the unprecedented rescue efforts must mean the Soviets had lost something extremely important.

The US started doing some digging of their own. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the US had established the Sound Surveillance System, or SOSUS, which was a network of listening devices that detected the movements of Soviet submarines. This system was hugely helpful to the US’ search, as it had detected an underwater explosion in the area the Soviets had been searching.

Eventually, the US narrowed the probable location of K-129 to just 5 miles and sent the submarine USS Halibut to investigate. After a month of frantic searching, Halibut found the wreck at a depth of 4,900 meters. The submarine was discovered on August 20, 1968. The U.S. spent the next three weeks analyzing and investigating the site, taking 20,000 photos while doing so. The submarine was damaged, but the wreck appeared to be mostly intact, and still contained some of the Soviet-developed R-21 missiles.

With the opportunity of retrieving Soviet nuclear weapons, the US decided to mount a recovery operation.

Project Azorian

Deciding to raise a 3,000-ton submarine and actually doing it are two different things. The scale of the project was going to be enormous, and the only way to keep it under wraps was by handing it over to the CIA.

At the time, nothing had been recovered from such depths, nor something of the size and weight of the K-129. Many ideas were floated around, like using rockets or inflatable balloons to raise her up, but none of these were deemed practical. In the end, it was decided that K-129 would be picked up by a claw lowered from a ship on the surface.

The CIA contacted a deep-sea mining company named Global Marine, which was considered one of the leaders in the industry at the time. The company was given the task of building a ship capable of hauling up the K-129. Lockheed was given the task of making the claw that would grab onto the submarine, known as the capture device.

To actually conduct the operation, the CIA needed a convincing cover story.

Who could they use that wouldn’t seem out of place funding an enormous operation on the ocean floor? They chose none other than Howard Hughes!

Howard Hughes was an eccentric billionaire business magnate who lived a crazy life with a seemingly endless supply of money. He had worked with the US government before and was certainly no stranger to weird projects.

Officially, Hughes was hunting for manganese nodules using new deep-sea mining methods, with Hughes Tool Company running the operation. They were armed with the Glomar Explorer, a 618-foot ship built by Global Marine. The ship had a large moon pool in its hold, that K-129 would be lifted into.

Lifting K-129

With the equipment, logistics, and cover story ready, the Glomar Explorer headed to the location of K-129 in mid-1974, 6 years after it sank. While over the wreck, it took some time to set up the equipment and lower the capture device. Throughout this time, the operation was harassed by Soviet vessels who were undoubtedly interested in the American activity, but the cover story had worked; the Soviets did not suspect a thing.

The team successfully grabbed onto the submarine and began the long and nerve-wracking process of lifting the submarine to the surface. All was going well until the capture device experienced a partial failure, causing K-129 to break apart, with over half of the submarine falling back down. The remaining sections were raised up and placed into the hold of the Glomar Explorer, which sailed back to the US.

The CIA planned a second operation to recover the rest of the wreckage, but Project Azorian was exposed by a reporter, forcing the CIA to abandon any future attempts.

Although only part of the submarine was recovered, it is rumored that what was brought up still provided US intelligence services with plenty to look at. What was actually recovered is still classified to this day. Reportedly, documents and nuclear torpedoes were included in the haul.

The wreck allowed the US to learn more about Soviet submarine design along with gaining an understanding of Soviet technology.

It’s estimated that Project Azorian came at a cost of about $800 million, or $4 billion in today’s dollars. It was one of the most secretive and expensive projects of the Cold War.

More From Us: Cold War Fun: A 1950s Science Kit That Contained Real Uranium

Sadly, six bodies and the remains of more were found amongst the torn and twisted metal. They were given a recorded burial at sea by the Glomar Explorer, recordings that were handed over to Russia in 1992.