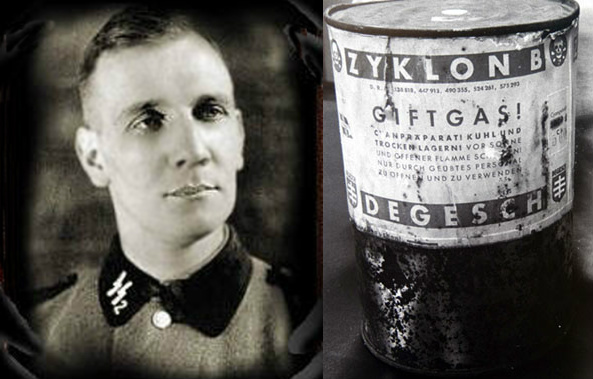

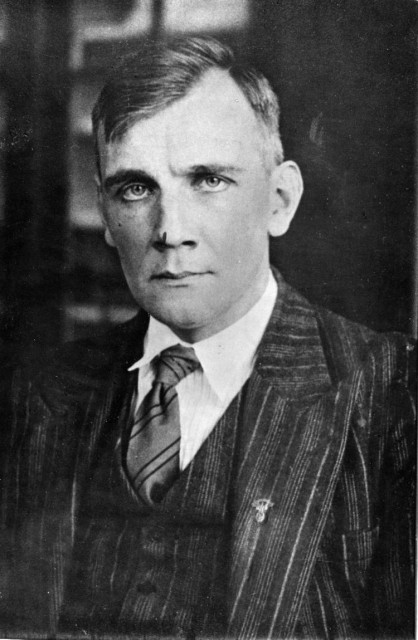

Kurt Gerstein (1905-1945), an SS officer assigned to the Hygiene Institute of the Waffen SS, was called upon to assist in the implementation of the “Final Solution.”

Gerstein was the sixth of seven children born to a well-established Lutheran family in Muenster, in the German state of Westphalia. Gerstein’s father, an overbearing judge and adamant German nationalist, instilled an unwavering patriotism in his children. Gerstein’s mother, worn out from bearing and raising children, died when he was young. Neither of Gerstein’s parents had time or energy to spend on him; as a result, much of his early care was provided by a devoutly Catholic maid, a woman recorded only as Regina.

Although an exceptionally bright child, Gerstein was a less than ideal student who skipped classes and ignored his schoolwork. Despite his flawed scholastic record, he easily obtained his Abitur in 1925 and went on to study mining engineering. He received his degree from the university in Marburg in 1931.

Initially, Gerstein felt it was his patriotic duty to support the Nazis. Moreover, membership would diminish pressure from his father and brothers, all of whom had joined the party in early 1933. Gerstein therefore joined the Nazi party on May 1, 1933, five months after Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor.

Perhaps due to his unfulfilling home life, his parents’ apparent lack of interest in religion or in him, or the religious devotion of his maid and early companion, Gerstein had become an active member of the Confessing Church in his teens. He supported Christian education of young men. Obsessively dedicated to the movement, he committed all of his spare time and much personal revenue to the cause. It was through his involvement with the church that he came into conflict with the Nazi regime. As the preachings of the Confessing Church came into conflict with Nazi ideology, the German state gradually impinged upon the church and its organizations. Gerstein had to choose between defending his church and supporting his nation. For a while, at least, he chose his church.

At the end of January 1935, Gerstein stood up openly for his faith at a performance in Hagen of a play (Wittekind) approved by the regime. The play spoke against God, and Gerstein spoke against the play. Storm troopers quickly pounced on Gerstein and beat him behind the theater. Seemingly undeterred, within little more than a year Gerstein was arrested for preparing to mail several thousand anti-Nazi pamphlets in favor of preserving church autonomy. This time Gerstein was far less lucky. He was jailed briefly, and expelled from the Nazi party.

Unable to find work after his release from prison, Gerstein returned to school to study medicine. From 1936 until 1938, he lived in Tuebingen with his wife, Elfriede Gerstein (nee Bensch), whom he had married on August 31, 1937. He continued to speak out against the Nazis. In July 1938 he was arrested and charged with high treason. During the pretrial investigation, Gerstein was held at Welzheim prison. Six weeks later, he was released.

With the help of his father and several influential Nazi party and SS officials, Gerstein was readmitted to the Nazi party with provisional membership on June 10, 1939. This not only gave him a fresh start with the party, but also enabled him to obtain another position in the mining industry.

In mid-February 1941, Gerstein discovered that his sister-in-law, Berta Ebeling, had died at a psychiatric hospital in Hadamar, Germany. He had heard rumors that the German government had embarked on the so-called Euthanasia Program, which involved the systematic murder of persons with disabilities who were living in institutions. The death of his sister-in-law seemed suspicious under the circumstances. According to a friend of Gerstein’s, Ebeling’s death added to a growing list of factors contributing to Gerstein’s curiosity and concern about what was going on in the German state. He decided the best way to find out was to join the SS, a move that would clear him of suspicion, given his past opposition to Nazi rule.

According to his undeniably favorable biographers, Gerstein applied and was accepted into the SS in March 1941, despite his dubious record. There is still some controversy regarding the chronology of events in the first half of 1941. Although it is entirely possible for his sister-in-law to have been a victim of the Euthanasia Program, it is still unverified that she died before Gerstein applied to join the SS.

After training for two months in a sanitation replacement battalion, Gerstein was assigned on June 1, 1941, to the Hygiene Institute of the Waffen SS in Berlin. This agency was subordinate to the SS Operations Main Office. In the Hygiene Institute, he distinguished himself through his comprehensive understanding of engineering and sanitation. His most important contribution was in the development of techniques for vermin control and maintaining quality drinking water for combat troops. On November 1, 1941, he was appointed as a specialist, SS Second Lieutenant, in the Waffen SS. On April 20, 1943, he was promoted to SS First Lieutenant in the Waffen SS.

Because of his position in the Hygiene Institute and his expert knowledge of decontamination techniques, Gerstein was called upon to assist in the implementation of the “Final Solution.” He was responsible for the delivery of large quantities of Zyklon B toAuschwitz and other camps. He also was invited to inspect theAktion Reinhard killing center at Belzec, where the SS staff used carbon monoxide gas in the gas chambers to murder prisoners. On this occasion, in August 1942, he observed a mass killing of Jews at Belzec.

In his postwar confession, Gerstein recorded what he saw at Belzec in great detail. He described the process by which trainloads of Jews entered the camp; their possessions were taken and their hair shorn. They were made to undress and crowd into a chamber (designed to look like a shower-room) so tightly they could not fall as they suffocated. Gerstein took no satisfaction in this process. He later maintained to friends that this experience made him determined to inform the world of the horrors taking place in the killing centers. He also claimed to friends during the war that he had, on at least one occasion, failed to deliver a shipment of Zyklon B gas and instead disposed of it.

Among the contacts Gerstein hoped would spread word of what he had witnessed were Swedish diplomat Baron von Otter, the papal nuncio in Berlin (Father Cesare Orsenigo), numerous members of the Confessing and Lutheran churches, and opponents of the Nazi regime. As he told those who would listen, he dreamed that the Allies would drop pamphlets across Germany; the pamphlets would inform people about what was really happening and thereby prompt the public to demand that the murder cease. Despite Gerstein’s efforts, those dreams never became reality.

By April 1945, the destruction of the Third Reich was imminent. Gerstein turned himself in to French authorities in the town of Reutlingen. In his statement, he declared that he had surrendered to make available his knowledge to punish those responsible for the atrocities. Ironically, however, Gerstein became not a witness but a suspect. At the end of May 1945, he was moved from a hotel where he had been staying under semi-house arrest to the jail in Konstanz and later to Cherche-Midi Prison in Paris. In Paris, he drafted his final statement, now known as the Gerstein Report. In this report, he recounted all that he had seen during his service with the SS. It was here he described his experience at Belzec and his conversations with von Otter and other foreign officials.

In his statement, Gerstein sought to deflect suspicion from himself as a Nazi offender. Whether it was the nature of the accusations against him, the profound distress of failing to slow the implementation of the “Final Solution,” or his fear of being convicted for his SS role, Gerstein hanged himself in July 1945.

On August 17, 1950, a denazification court in Tuebingen found Gerstein to have been a Nazi offender for his assistance in the production and delivery of Zyklon B. His widow was denied a pension. Almost 15 years later, with the help of Baron von Otter and other well-placed friends, Gerstein’s wife obtained posthumous pardon for her husband in January 1965.

Though Kurt Gerstein has been dead for almost 60 years, the exact nature of his relationship with the Nazi party and the SS remains a mystery. To his friends and admirers, however, including those to whom he spoke during the war, he was a convinced opponent of the Nazi regime.

Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Further reading

Friedländer, Saul. Kurt Gerstein: The Ambiguity of Good (New York: Knopf, 1969).

Hébert, Valerie. “Disguised Resistance? The Story of Kurt Gerstein.” In Holocaust and Genocide Studies 20, no. 1 (2006): 1-33.

Joffroy, Pierre. A Spy for God: The Ordeal of Kurt Gerstein (New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, Inc., 1971)