Graham Scott, of Wessex Archaeology, co-author of a new book on the disaster of the SS Mendi in 1917 that took the lives of 616 South Africans, said it well: The men of the Mendi were treated as unfairly in life as they were in death.

Yet the tragedy, one of the worst maritime disasters in British waters in the 20th century, was remembered only as a historical footnote because 607 of the victims were black.

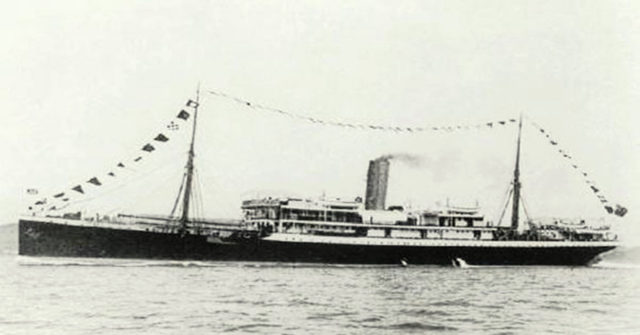

The Mendi steamship was ferrying 823 men from the 5th Battalion South African Native Labour Corps (SANLC) when it was struck by a far larger vessel not that far from the Isle of Wight.

After the disaster, white South African leaders awarded no medals to the black servicemen, dead or alive, from the Mendi. Such honors were exclusively for white officers. Only after apartheid ended was the tragedy properly memorialized.

How the men came to be aboard the Mendi is traced to the start of the First World War. To be victorious on the Western Front more manpower, in addition to the 400,000 Army volunteers was required, including non-combatants. As that number escalated to two million by 1916, there was an even greater need for extra men to operate ports, build roads, railways, trenches and to move supplies. The British government turned to its dominions and colonies for a Labour Corps.

The white South African government was initially hesitant, concerned about giving military training to black men who did not have the vote. They relented, eventually, and men headed for war in troop ships such as the SS Mendi. It left Cape Town in January 1917, entering the English Channel in the wee hours of February 21.

The Labour Corps were on the way to France. The Mendi was 20 kilometers off the Isle of Wight when it was hit by Royal Mail Steam Packet company cargo ship Darro going at top speed despite it being pitch black and foggy.

Darro captain Henry Stump later claimed he was ordered in France to make the English coast before sunrise. He was also concerned about German U-boats.

The collision slashed a deep hole in the side of the Mendi, which went to the bottom of the ocean in 20 minutes.

Very little of the disaster is recorded in history texts. Much of what is known was gleaned from the stories related by the 267 survivors.

With an insufficient number of lifeboats, hundreds of men had to grasp primitive life rafts. Despite the best efforts of the destroyer Brisk, Mendi’s Royal Navy escort, many were not found or rescued.

An inquiry placed the blame on Stump for the collision and chastised him for failing to help rescue the men. His captain’s certificate was suspended but the disaster was soon forgotten.

Over 21,000 South African men served Britain in the final two years of the war, often completing dangerous work and just as often treated harshly. Many anticipated the war would mean improvements for them due to their service and sacrifice.

However, the South African Labour Corps, including those who survived SS Mendi, were never awarded British campaign medals.

In 1995, Queen Elizabeth on a visit to South Africa, was accompanied by President Nelson Mandela as she unveiled a monument to the Mendi dead at Avalon Cemetery in Soweto, outside Johannesburg.

In addition, in 2003 a medal awarded for acts of courage by South African citizens was created in their honor: the Order of Mendi for Bravery.

Diver Martin Woodward located the wreck of the Mendi in 1974. He has since displayed many artifacts in his museum at Arreton on the Isle of Wight.

The new book published by Historic England to commemorate the loss of the Mensi is titled,‘We Die Like Brothers.’

And tributes will involve Royal Navy and South African warships. Divers from the Fleet Diving Unit in Portsmouth will carry out archaeological surveys and place a South African flag on the wreck.

John Gribble of the South African Heritage Resources Society says there was bitterness in South Africa at the way SANLC had been disregarded.

A memory of the sacrifice was preserved in black communities and it slowly became a sign of resistance against inequality and discrimination. This concerned the apartheid government. Now, the Mendi is notable for the same reasons, Mirror reported.

Scott said it is not lost upon us that the Mendi is now seen as a significant part of the maritime inheritance of both South Africa and Britain. It is a lesson of how their maritime heritage knows no boundaries.

For a century they have correctly honored the supreme sacrifice of the service personnel who fought and were killed in the First World War, Scott explained. Now is the time to remember and honor the non–combatants who traveled great distances to assist Britain and many times lost their lives to do it.