One rather striking detail that is immediately noticeable about many WWII combat aircraft, regardless of which nation fielded them, is the fact that they were painted in camouflage color schemes.

While some military aircraft are still painted with camouflage color schemes today, such patterns are nowhere near as widespread and prevalent as they were on the military aircraft of WWII – the aircraft of which were painted in camouflage hues ranging from browns, drab greens, and other earth tones to grays, blues, black and even, in the seemingly counterintuitive color scheme of British spy planes, pink.

The first question many people ask when it comes to aircraft being painted in camouflage color schemes, especially those involving earth tones such as browns, olives, and drab green tones, is why? Camouflage paint schemes in these colors and tones certainly make sense for ground-based vehicles like tanks, jeeps or army transport trucks, but why would such colors be needed for vehicles intended to operate in the sky?

The answer, at least for the first part of the Second World War, when air superiority was hotly contested, was that the planes needed to be protected when they were at their most vulnerable – on the ground.

Military aircraft were expensive investments, costly and time-consuming to produce, and thus of immense value both as assets and targets. An enemy aerial bombing raid over an airfield or airbase, where dozens of planes could be targeted and destroyed in a matter of minutes, could prove disastrous.

However, as laser-guided weaponry only began to be used in the 1960s, and smart bombs and missiles from the 1990s onwards, in WWII bombs were guided by what the human eye was capable of seeing. An effectively camouflaged aircraft on the ground could be nigh on invisible unless the attacking pilot was flying rather low to the ground – which would put him at risk from anti-aircraft defenses.

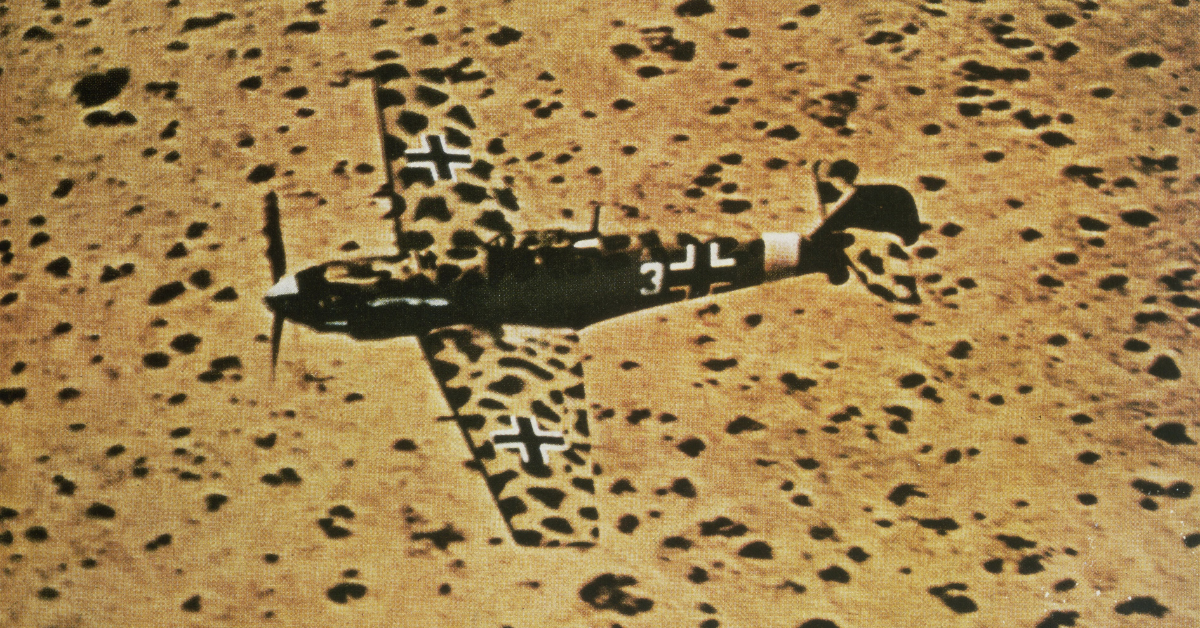

Each nation participating in the war had its own specific camouflage paint schemes for the various types and models of aircraft it fielded. These were so numerous, particular and specific, in fact, that entire books have been written on the subject.

To (very crudely) sum up such a vast array of color schemes and patterns, numerous models of fighter planes were generally painted with earth tones – an array of browns, tans and greens – on top. Their undersides were painted in tones that would blend in more with the sky when seen from the ground: flat tones of gray or blue, rather than the disruptive patterns of the tops of the planes.

Various models of bombers, which often operated at night, were sometimes painted differently than fighters. Their undersides, or in some cases their entire bodies, would be painted black, in order to provide camouflage against the night sky. As the war progressed, however, some bombers had their undersides painted in lighter hues, to blend in with the glow of light pollution from the cities below them.

Perhaps the most interesting camouflage color scheme was that of the British Royal Air Force’s photo-reconnaissance Spitfire planes, which were painted pink. Not neon pink, of course, but a pale and subtle hue of pink.

These planes, which were unarmed (to save weight so that they could fly faster and farther) and equipped with cameras, needed to fly quickly into and then out of enemy territory, and the pink tone used was actually ideal for camouflaging them against dawn or dusk skies. Indeed, they could maintain near invisibility beyond 300-600 feet under the right conditions, which was more than enough to get in and out of hostile territory virtually undetected.

In the latter years of the war, attitudes toward camouflage paint on planes began to change. After the Allies achieved definitive air superiority, they began to paint their planes more simply, or do away with paint altogether.

Since they had achieved air superiority, there was little danger of their planes being bombed, and thus camouflaging them against the ground was no longer necessary. This applied to American aircraft in particular, many of which were stripped of paint completely or, for those produced in the latter years of the war, simply not painted in the factory, and covered only with a coat of wax or clear lacquer.

Unpainted airplanes had an advantage over their painted counterparts: they were lighter. Not by a great degree, but for a small fighter, a weight loss of a few dozen pounds equated to faster speeds in the air (which was further enhanced by better aerodynamics without the drag created by matte paint), greater maneuverability, and the capability to fly farther.

On larger planes, particularly the biggest bombers with a large surface area to cover, forgoing a coat of paint could save a few hundred pounds, which meant that a larger payload of bombs could be carried. By the end of the war, a large portion of American airplanes had either had their paint removed, or had come out of the factory unpainted.

While camouflage paint on military aircraft did generally fall out of fashion after the Second World War – especially with the improvement of radar systems, as well as the introduction of heat-seeking missiles – it was never completely abandoned, as its usefulness in terms of disguising aircraft on the ground from human eyes above is as pertinent now as it was during WWII.

Even with the types of advanced, technologically-enhanced camouflage methods that are employed today, such as computer-controlled active camouflage panels, multi-spectral camouflage, and digital camouflage, the usefulness of good old camouflage paint schemes to fool the human eye is still used on a number of military aircraft across the world.