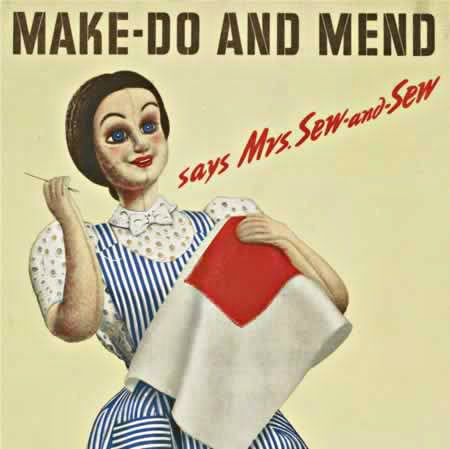

The ‘make do and mend’ ethos, the culture of repairing and saving, gaining a revival in today’s society was grounded during the conflict which lasted from 1914 to 1918 – the Great War.

Cooking with the use of a hay box, reusing coal dust for fire briquettes, using black dye made from a concoction of fig leaves for the funereal silk and making butter using mashed potatoes…these are just some of the household measures encouraged by the government and the media during the Great War. Citizens had to adopt these ‘make do and ‘mend’ efforts. Supplies were scarce and most were going to bed in hunger.

When the Britons showed the spirit of resourcefulness with their enthusiasm, making up for the starvation and scarcity so prevalent throughout the country, it made the backdrop for the now famous ‘make do and mend’ ethos which then rose again in the 1940s during the Second World War.

The propaganda behind the ‘make do and mend’ mentality may not have geared up until the warring years against Nazi Germany (1939-1945), people had already learned the ways to keep chicken, how to turn villa gardens to potato patches and the many forms of mending clothes with the use of netting and other clothing leftovers way back in 1916. There are even villages who went as far as organizing waste collection points and delivering these collected wastes to homes who had volunteered to keep pigs.

The people’s eagerness in adapting to the ‘make do and mend’ ideology was evident in the letters they sent to WWI-era newspapers. Their ingenious suggestions ranged from making jam with the use of honey instead of sugar to making savory jellies out of wild rowan berries. Some even went as far as suggesting that the garden squares of London be converted into poultry runs!

Newspapers ran during the Great War period strongly emboldened their readers to their own foraging for their food. The then Manchester Guardian had an article dated July 1915 titled River Fish for the Table which roused readers who didn’t like the ‘ill-cooked pike’ to try beam and carp instead in place of meat which was scarce all throughout the war. Another article of the said paper dated April 1918 also reported that the wood pigeon provided good meat all thanks to a bumper acorn season during that winter.

In addition to these very uncommon sources of meat and protein, roast seagull and their eggs as well as cakes made from the bracken root floor were also suggested.

Home front destitution turned severe during the Great War’s last two years. In her diary, Lillie Scales wrote in 1917 that the cakes bought during those times were simply horrid. Puddings made from carrots and potatoes instead of flour were nicer. She also noted that she had lost two ounces since the war years started.

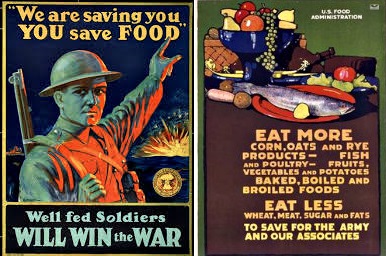

In another diary entry dated March 1917 and written by wartime teen Miss E V Tregellis, she remarked rather grumpily that they were put on war bread and how posters on the streets reminded everyone not to consume too much of the food item.

WWII’s ‘Make Do and Mend’

The 1940s’ ethos of ‘make do and mend’ is enjoying a revival today. Nevertheless, this 1940s ideology was also just a reinvention from the measures taken during the Great war.

According to a professor of history at the University of Mississippi, Susan Grayzel, nobody anticipated the food shortages nor the rationing during WWI. Of course, the working class already knew beforehand how to make do with so little supply. The middle class, on the other hand, had to learn these same lessons the hard way — right at that point.

So, when the 1930s rolled in and another war loomed on the horizon, the government looked at those lessons and decided to put up the ‘make and do’ strategy.

Professor Grayzel added that it greatly helped how women of the Second World War had First World War mothers who taught them the values of frugality and economy through the ‘lived memories’ the latter passed on to them.

The passing of these ‘lived memories’ still continue to this day.

Nevertheless, not all activities of the ‘make do and mend’ ideology are applicable today. The method in making briquettes from coal dust may trigger anxiety. In similar fashion, modern day consumers might find “potato butter” – made from 1 ounce of margarine and 140 ounces of sieved mashed potato – quite difficult to swallow. It is also now considered illegal to kill seagulls and disturb their nests.

Hay box or residual heat cooking is another matter, though. It is still commonly used during camping trips, power cuts or by simply thrifty consumers.