When you are a small city-state enjoying a precarious existence and surrounded by potentially hostile other city states, and especially the military state of indomitable Sparta, it might not be a good idea to antagonise a monolithic superpower. This however, is exactly what happened in 499 BC when Greek colonists revolted against their Persian overlords and razed the city of Sardis to the ground. They were aided in their rebellion by Athenian soldiers who had been sent to assist their fellow Greeks. When the Persians finally succeeded in crushing the revolt in 495 BC they turned vengeful eyes upon the aider and abettor of the uprising – the democratic city-state of Athens.

King Darius of Persia initiated the Persian retaliation by blockading the Greek mainland. Then, having drawn upon the enormous resources of the monolithic Persian empire, Darius dispatched an enormous armada of 600 ships and 25 0000 soldiers. The Persian commander-in-chief, Datis, chose Eritrea as the first target upon which to deliver his master’s wrath. The city of Eritrea was besieged and swiftly overwhelmed. In Athens, men learnt with dismay that Persian malice had even gone as far as destroying the Eritrean temples dedicated to the Greek gods. If the Persians did not scruple to destroy temples which, in the ancient world, were normally treated with reverence by friend and foe, what would they not do Athens? Athenian fears were later further heightened when news reached the city, via beacons, that the Persians had successfully effected a landing at Marathon within a few days march of the Athens herself.

At this perilous juncture in Athens’ future, one heroic Athenian general, Miltiades, rose to the challenge presented by the Persian juggernaut. Miltiades disdained any idea of capitulation and persuaded the Athenian leaders to send out 10,000 hoplites against the Persians stationed at Marathon. His proposal was adopted and the heavily armed and bronze armoured hoplites were dispatched to the Marathon beachhead under the overall command of Callimachus, the Athenian War Archon. When the Athenians reached Marathon, however, Callimachus turned over his command to Miltiades, as the latter was by far the most eminently suitable to lead the army in terms of his combat leadership experience and tenacious determination to oust the Persians from Greece.

With the arrival of 1,000 Plataean soldiers, Miltiades force grew to 11, 000 battle ready Greek patriots. In vain, however, did the Athenians look for further assistance from other Greeks, especially from the powerful military state of Sparta and Miltiades realised that if his force was defeated at Marathon, nothing would stand between the Persians and Athens. While the Greek army now occupied a favourable defensive position upon rugged, sloping high ground they could not take the offensive against the much larger Persian force. A stalemate thus ensued until news was brought to Miltiades that the Persians were about to embark their cavalry under Artaphernes, and make a rapid descent upon Athens while her army was in the field. The Persian plan was a bold one but also coldly calculating. Entrenched in their defensive position the Athenians would face an inevitable choice of two terrible options. The Athenians could attempt to stop the Persian cavalry from disembarking – which would force them to leave their defensive positions and engage in a pitched battle against a numerically superior infantry force of Mede and Persian foot soldiers, or, the Athenians could abandon the field of battle, retrace their steps to Athens and hope to arrive before the Persian fleet, while simultaneously fighting off the full weight of the Persian infantry which would immediately attack the retreating Greeks once they had evacuated their defensive position.

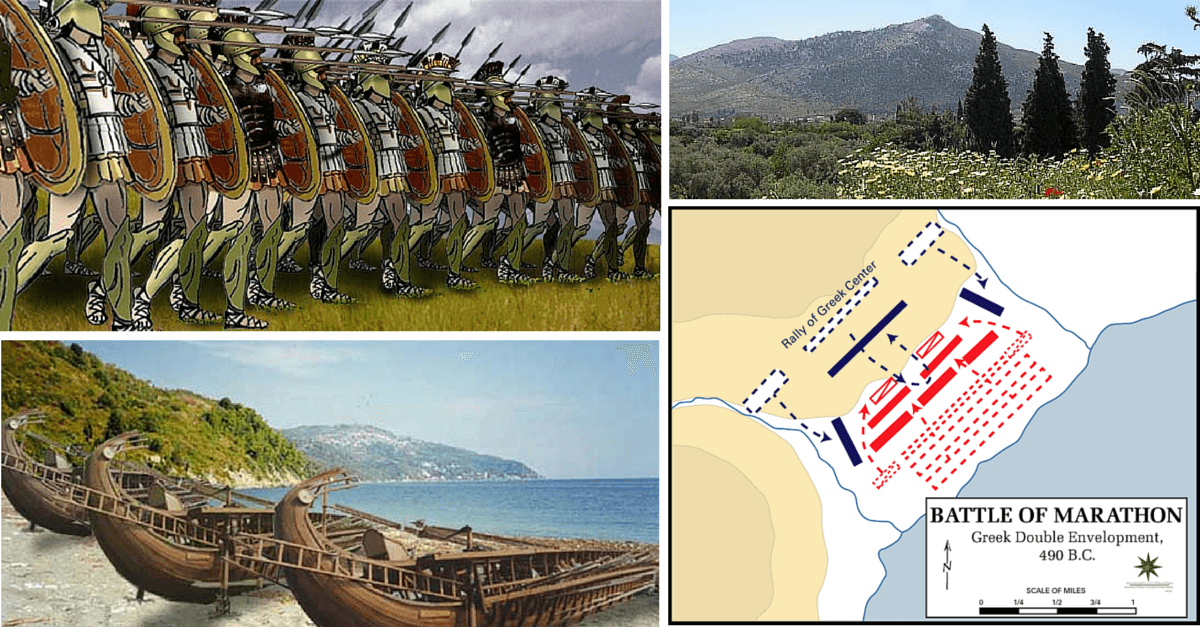

Faced with these two options, both of which were fraught with danger, Miltiades chose to take the Persians head on. The Athenian general deployed his hoplites in the centre with only four ranks, while the flanks were arranged in eight ranks. This maneuver presupposed an eventual break in the Athenian centre at which time, as the Persians pressed their advantage, the Athenian flanks would envelope the Persian onslaught – a tactic that was to be replicated by such military geniuses as Hannibal at Cannae and Shaka in southern Africa. When these military dispositions had been accomplished, Miltiades gave the order to advance. When the Persians saw that the Athenians were actually preparing to hazard an assault upon their numerically larger force, they were struck with amazement and believed them to be mad. The Persian archers quickly prepared to repel the advance but when the Athenians reached the ‘beaten zone’ i.e. the range at which Persian archers could most effectively loose their arrows, the entire force broke into a run and hurled themselves upon the astonished Persians. As Miltiades had foreseen, the Athenian centre soon gave way under the tremendous pressure of Persian numbers. When the Athenian centre broke, the Persian force hurled itself headlong into the gap left by the retreating Athenians. At this point, Miltiades swung his flanks upon the Persians massed in the centre. Panic ensued in the Persian ranks, and the entire centre broke and began to flee to the safety of the ships beached on the Marathon shore. In the debacle that followed, the Athenians continued to press their advantage and cut a swathe of slaughter amongst the retreating enemy and even managed to capture several Persian war vessels.

The victory at Marathon had saved Athens. The historian Herodotus records that nearly 7,000 Persian soldiers were slain on that day for the loss of 200 Athenians and Plataeans. While fully regarding the part played by Miltiades’ strategy, most historians are of the opinion that the truly decisive factor that tipped the scales against the Persians was the sheer raw courage which the Athenians displayed in the face of the Persian juggernaut. This bravery was exemplified in the actions of one soldier after the battle. Amidst the joy of victory, an Athenian soldier threw off his armour and ran towards Athens. This was the famous dispatch-runner Pheidippides who ran over 40 kilometres back to Athens where the anxious and desperate populace awaited news of the outcome at Marathon. Pheidippides drew upon all his reserves of endurance, ran all the way back to Athens, managed to gasp out “We have the victory” and then immediately dropped dead from exhaustion.