On December 29, 1890, soldiers with the US Army opened fire on hundreds of Lakota Sioux. The group of Native Americans was largely unarmed and included several women and children. The incident, known as the Massacre at Wounded Knee, is considered one of the darkest moments in American history.

The Ghost Dance movement

By the late 1880s, American forces had seriously encroached on Native American land. Numerous agreements and treaties meant to protect the natives had been completely ignored. The bison herds, essential to the lives of the Great Plains Indigenous peoples, had also been hunted to near extinction.

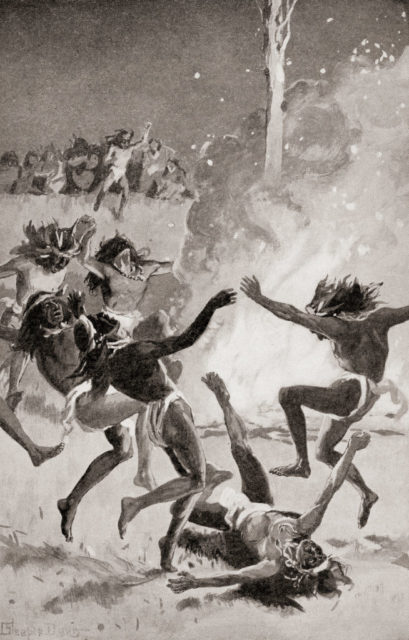

A Paiute prophet named Wovoka had a vision that Jesus Christ would return to earth, in the form of a Native American. He believed this return would lead to an end to the encroachment of his people’s land. As a result, the Ghost Dance movement, which helped unite tribes, began to spread. Celebrants would wear specific shirts and believed performing the dance would bring about the prophecy.

US settlers were concerned about the movement and thought it could be the prelude to an attack.

The killing of Sitting Bull

Sitting Bull was a holy man and leader of the Lakota people. In 1889, he went on tour with Buffalo Bill Cody, which earned him large sums of money. Upon his return, he met with the leaders of the Ghost Dance movement and allowed them to use his campground. While not an active participant in the dancing, he was considered an instigator by US Indian Agents.

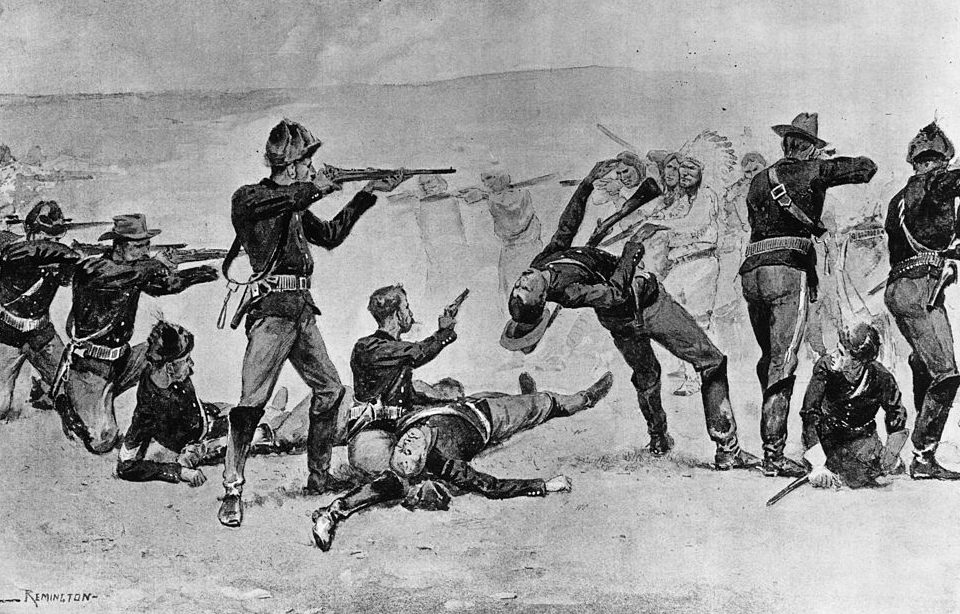

Worried Sitting Bull could flee the compound with the Ghost Dancers, 39 police officers and four volunteers went to arrest him. Sitting Bull refused to comply, and a fight broke out. After a Lakota shot Lieutenant Henry Bullhead, Sitting Bull was shot and killed by Bullhead and another officer named Red Tomahawk. He died soon after.

The Massacre at Wounded Knee

Following the death of Sitting Bull, 200 members of his Hunkpapa band left camp, fearing reprisal. They joined up with Chief Spotted Elk. Spotted Elk led a group of about 350 Native Americans to the Pine Ridge Reservation.

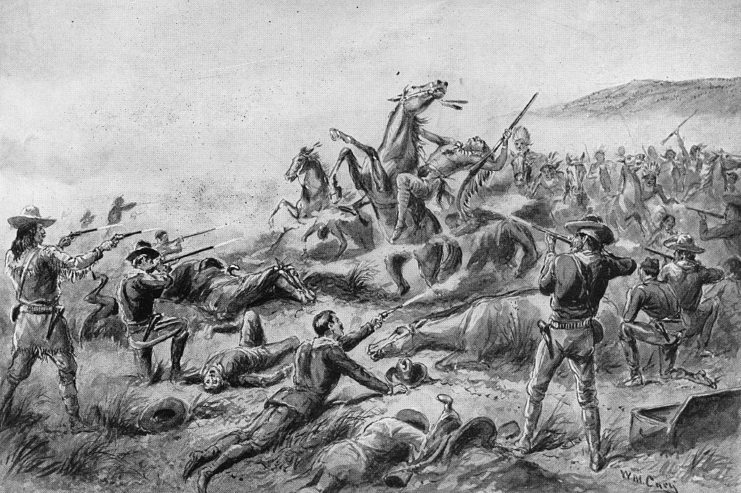

On December 28, 1890, the US Army’s 7th Calvary Regiment set upon the group. They led them five miles ahead and told them to set up camp. The following day, the soldiers went to confiscate weapons from the group. One man, Black Coyote, was deaf and had a new rifle. According to sources, he did not understand the instructions and was reticent to give up his weapon. Another man, Yellow Bird, began to start the Ghost Dance.

In the struggle, Black Coyote’s rifle fired, and soldiers began the massacre of mostly unarmed men, women and children. The actual number of Native Americans killed in the bloodbath is unknown, but estimated to have been between 150 and 300.

Black Elk, an Olgaga Lakota medicine man present at the scene, later said:

“I did not know then how much was ended. When I look back now from this high hill of my old age, I can still see the butchered women and children lying heaped and scattered all along the crooked gulch as plain as when I saw them with eyes still young.

“And I can see that something else died there in the bloody mud, and was buried in the blizzard. A people’s dream died there. It was a beautiful dream. And I, to whom so great a vision was given in my youth — you see me now a pitiful old man who has done nothing, for the nation’s hoop is broken and scattered. There is no center any longer, and the sacred tree is dead.”

Military Honors and controversy

Following the 1890 massacre, 20 of the Army soldiers who took part were awarded with the Medal of Honor, the highest commendation within the US military. Native American advocates have long argued the medals should be rescinded, since the massacre was an act of cruelty, rather than an act of bravery.

In March 2021, the Remove the Stain Act was introduced by Senators Jeff Merkley (D-OR), Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Congressperson Kaiali’i Kahele (D-HA). Warren said of the bill:

“The horrifying acts of violence against hundreds of Lakota men, women and children at Wounded Knee should be condemned, not celebrated with Medals of Honor. The Remove the Stain Act acknowledges a profoundly shameful event in U.S. history, and that’s why I won’t stop fighting for this effort to advance justice and take a step toward righting wrongs against Native peoples.”