The scars and ghosts of the Second World War sometimes resurface to remind us of an earlier, more savage time. These manifest usually in the form of old war relics, like perhaps an old unexploded mine, a diary locked in an attic, or in the ammunition pockmarks still dotting the walls of many European cities, where the paint and mortar didn’t take. And perhaps most often, these old scars return to us in the form of submerged boats and battleships, lost at sea after a battle. In one such case, the government of Sri Lanka didn’t wait for one of its old war-relics to resurface but instead raised it themselves.

Built in the early 1920s by the Leven Shipyard of William Denny and Brothers in Dumbarton for the British and Burmese Steam Navigation Company and the Burma Steam Ship Company managed by P Henderson and Co, the Sagaing had originally been launched in 1924. It spent the majority of its life at sea as a transport ship, shuttling passengers and goods between the United Kingdom and Burma (present-day Myanmar), until the advent of the Second World War altered its purpose towards carrying aircraft and ammunition.

It survived one attempted attack, in October of 1939, when it was pursued by a German U-boat, causing some passengers to panic and abandon ship aboard lifeboats, only to be lost at sea. The ship was placed under the Ministry of War Transport at some point before April 1942 and came under the operational control of the Burma Steamship Company. She sailed under the Burmese flag in order to avoid Board of Trade safety regulations.

It ended its rather short life on April 9th, 1942, when it was bombed during Japan’s Indian Ocean raid, while sitting in Trincomalee harbor, by the Kidō Butai, the exact same naval force that attacked Pearl Harbour the year before. It would, in fact, be the last operation carried out by that particular Japanese carrier force.

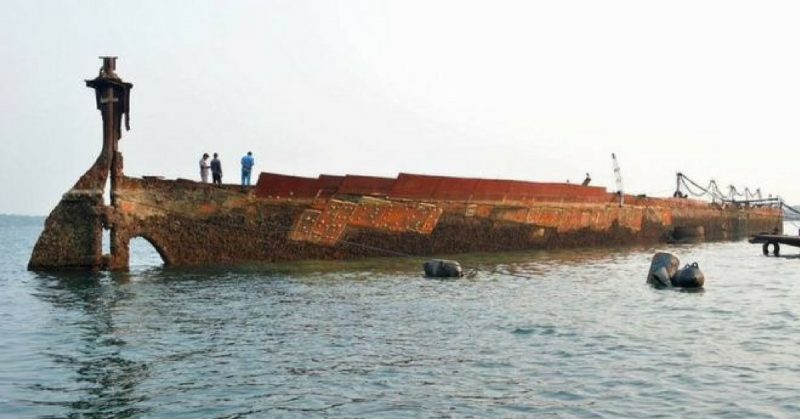

The day the Sagaing was bombed, it was transporting a cargo of four aircraft, a Walrus and three disassembled Albacores, for the Allies. The explosion caused a fire in the lower decks, and it was promptly abandoned leaving three dead, but the ammunition was salvaged. It then drifted into the Malay cove to be sunk by further shellfire. A little more than a year later, the damaged 452ft long vessel was used as a pier for other ships. It rested under more than 30 feet (or 10 meters) of water for the next seventy-four years until only recently.

The responsibility of salvaging and removing the Sagaing fell to Eastern Naval Command, spearheaded by the Eastern Command Diving Unit and the Command Diving Officer Captain Krishantha Athukorala. That meant a team of nearly a hundred divers working specifically on that project. They were overseen by Director General of Operations, Rear Admiral Piyal De Silva, with assistance from the Tokyo Cement Company, which provided a crane barge and operator.

Curiously enough, the hull was rusted but otherwise completely intact. Despite this fact, the required repairs to the ship were extensive. In the end, the salvation operation took five months, because the structure of the vessel’s main body was understandably unsound, and required strengthening. Also, divers had to construct an entire artificial side of the ship in order to return buoyancy. The successful raising of the ship is largely considered a landmark achievement in the field of diving and salvage operations. The aim of the salvage mission was to make sea room for expanding berthing facilities in the harbor.

The ship’s ascent to the surface started on March 22nd. She was then towed to the sea off Trincomalee, where it was sunk again eight days later to preserve it.