It was just after 10 AM, June 4, 1942 over Midway, and Air Group Commander C. Wade McClusky Jr. had a tough decision on his hands. His group of dive-bombers, searching for a large Japanese carrier group known to be nearby, was already low on fuel, but still with no idea where the enemy might be.

Then the clouds over the Pacific momentarily parted, and McClusky spotted the wake of an enemy destroyer racing away at highspeed. It was the Arashi, and McClusky presumed it to be headed back to the Japanese fleet. Despite his perilous fuel situation, he decided to give chase. It may well have been the most critical decision of the entire Pacific War.

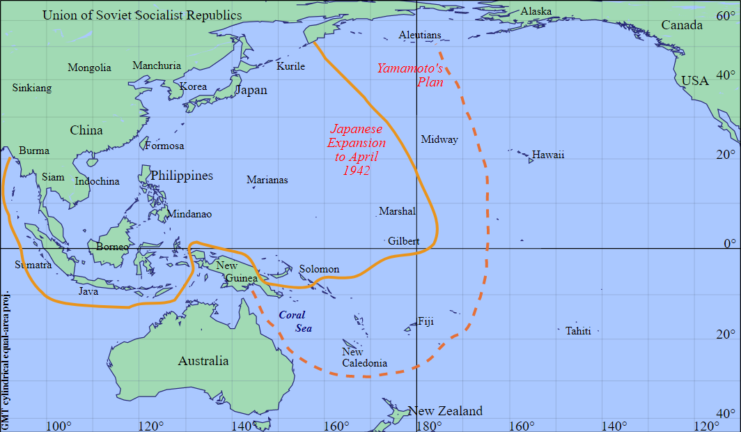

Since the Doolittle Raid on Tokyo of April 18, American intelligence station Hypo at Pearl Harbor had a clear sense that the Japanese intended to respond to the Doolittle attack by pushing their defensive perimeter farther east, north to the Aleutian Islands, and south to a point somewhere in mid-Pacific. That mid-point (referred as AF in intercepted Japanese communications) was believed to be Midway, a small atoll some 1300 miles west of Hawaii, but no one was sure.

Then, in late May Admiral Chester Nimitz, Pacific Fleet Commander, staged a clever ruse in which the American station at Midway sent a message indicating their water-evaporation units had broken down. Shortly thereafter, new intercepted Japanese communications restated that the water-evaporation units at AF were broken. Bingo.

The Japanese plan was to threaten Midway, forcing the American fleet to respond, then ambush the fleet as it approached, knocking the American Navy out of the Pacific Theater, once and for all. A simultaneous attack was to be launched against the Aleutian Islands of Atta and Kiska, part of the Alaskan Territory, this to gain a foothold on American territory. It was an ambitious plan.

With the recently decoded Japanese intelligence in hand, on May 27 Edwin Layton, Pacific Fleet Intelligence Officer, briefed Nimitz and his staff. Layton said he had calculated that the Japanese fleet would approach Midway on June 4, on a bearing of 325 degrees, and that at 7 AM they’d be 175 miles from the atoll; a remarkable intelligence assessment, that now put Nimitz in the driver’s seat. Despite decidedly inferior numbers, Nimitz decided to roll the dice, and ambush the ambushers.

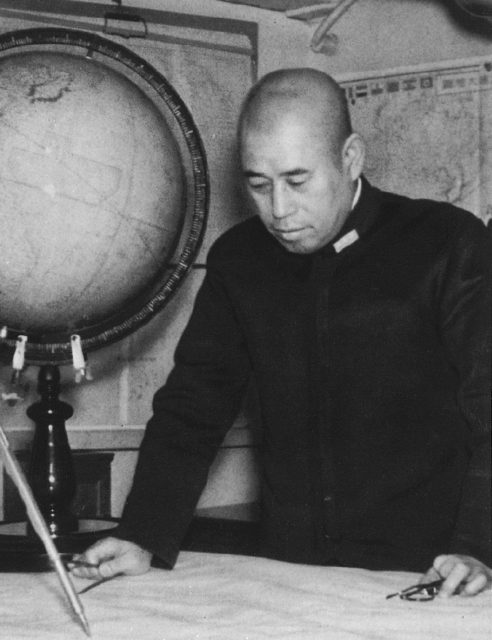

Early on June 4, the Japanese attack group was almost precisely where Layton had predicted. Commanded by Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the architect of the infamous Pearl Harbor attack, the First Carrier Strike-Force under command of Vice-Admiral Nagumo, was in the lead. This consisted of 4 carriers with 248 aircraft, 2 battleships, 2 heavy cruisers, and 12 destroyers. There was also a significant support force, following in its wake.

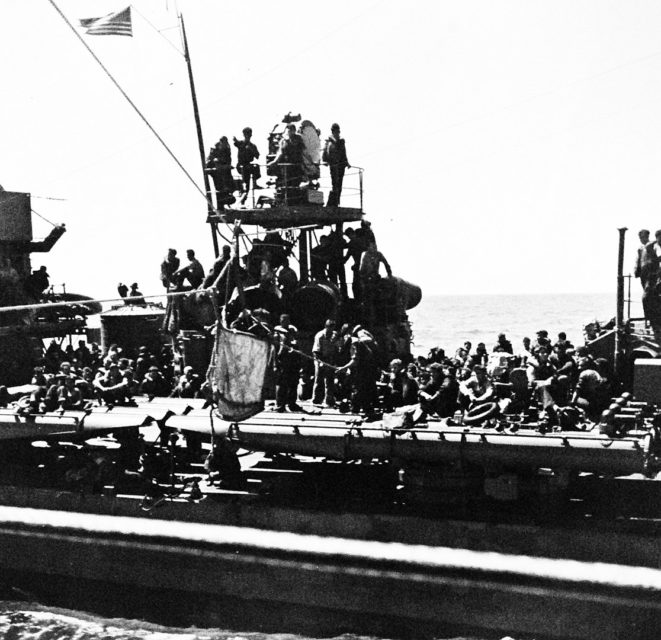

Initially, Nimitz had but two carriers to work with, Enterprise and Hornet, a force substantially inferior to what the Japanese had put to sea. The carrier Lexington had been sunk in the Battle of the Coral Sea, Yorktown severely damaged, and presumed to be out of action for months.

But frantic, around-the-clock repairs at Pearl Harbor, had put Yorktown back out to sea in 72 hours, gimpy, but game. That gave Nimitz 3 carriers hosting 233 aircraft, 7 heavy cruisers, 15 destroyers, and 16 submarines with which to confront the Japanese.

The Marines at Midway also had 127 land-based aircraft. Unfortunately, many of these planes were outdated, their pilots inexperienced, whereas the Japanese had state-of-the-art aircraft and battle-hardened pilots. Nimitz, like Yamamoto, was banking on surprise.

The Japanese approached Midway from the northwest, as the Americans waited in silence to the northeast. At 4:30 AM on the 4th Nagumo commenced his initial attack on Midway, launching 36 dive-bombers, 36 torpedo-bombers, and 36 Zero fighter-aircraft.

Importantly, at 5:30 that morning, an American observation plane spotted the Japanese fleet and radioed its position. The Marines on Midway responded with 26 fighter-aircraft, which were, unfortunately, no match for Japanese Zeros. The anti-aircraft batteries on the atoll faired-better, however, knocking-out 11 Japanese planes, and damaging 43 while under attack.

While the Japanese bombers caused problems at Midway, the damage they inflicted fell far below their threshold of expectations. If the Japanese were to land troops on June 7, as scheduled, far more damage would have to be done to the American base.

Meanwhile, between 7 and 8:30 AM, three flights of bombers and dive-bombers were launched from the airstrip at Midway. These located and attacked the Japanese fleet, but were entirely ineffective, driven off by Zero’s or downed by heavy anti-aircraft fire.

Notably, the Japanese still had no idea a substantial American battle-fleet was lurking just northeast of Midway.

It would take the Americans – still amateurs at large-scale carrier operations – hours to launch their first wave. These took-off between 7 and 8 AM, attacking piecemeal, rather than grouped, to save precious fuel. The Japanese fleet was then at the extreme limit of the plane’s range, hence fuel became an immediate problem.

One bomber group, using an incorrect heading, never located the enemy, and was forced to ditch. Nevertheless, between 9:30 and 10:00 o’clock, torpedo bombers launched from Enterprise and Hornet located the Japanese carriers – Soryu, Kuga, Hiryu, and Akagi – and immediately attacked.

Unfortunately, the slow-flying American planes were no match for the speedy Zeros, and their (mostly defective) torpedoes were equally ineffective. The torpedo-bombers were virtually blown from the sky, causing no damage, but they did momentarily occupy and confuse the Japanese high-command.

On the Akagi, Admiral Nagumo now had a problem of his own. When the initial attack on Midway reported minimal damage, he ordered his reserve planes armed with general purpose ordnance for a second run at the atoll. While this was taking place, Nagumo received a report that a Japanese scout-plane had spotted American warships nearby, but that report was maddeningly imprecise.

Were American carriers in the area? Should he switch, and rearm his planes with torpedoes? Without more, precise information, Nagumo could reach no decision.

Valuable time was wasted. Then Nagumo received confirmation that at least one American carrier had been spotted, but by then his first assault wave was returning from Midway and had to land. So, no strike could be launched until the first wave had been brought-in safely.

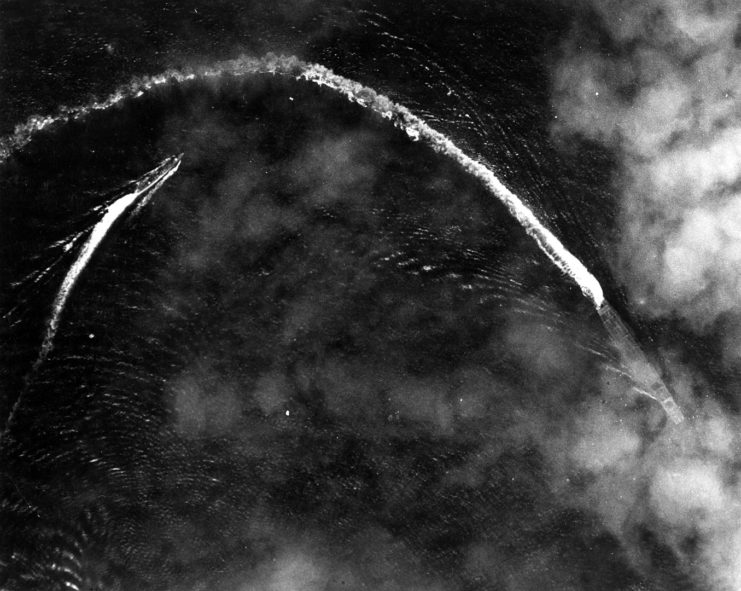

Thus, around 10:15, the decks of Kaga and Akagi were full of returning aircraft, flight hangers crammed with additional planes, bombs, and torpedoes stacked on the decks, while fuel lines lay open and exposed, due to hasty refueling, all this as Soryu and Hiryu were preparing to launch another flight. Meanwhile, Nagumo’s fighter cover had just flown-off, chasing the last American attack.

It was precisely at this moment when Air Group Commander C. Wade McClusky Jr. appeared overhead, still trailing the destroyer Akagi, and spotted the Japanese carrier group below. McClusky immediately ordered his entire group to attack, and the dive-bombers screamed out of the clouds, taking the undefended Japanese carriers by complete surprise.

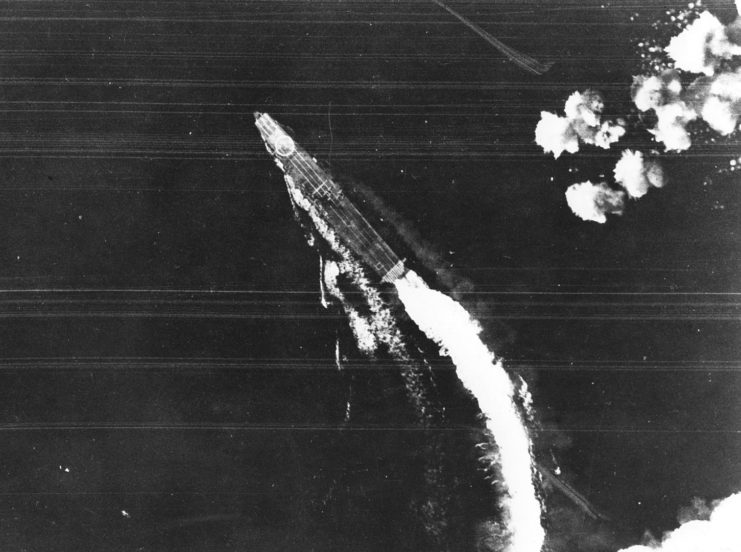

The devastation was immediate and appalling. Kaga took multiple direct hits from 500 lb. and 100 lb. bombs and exploded into flames. Akagi sustained a direct hit that penetrated to the upper hanger-deck before exploding amongst fueled planes, causing massive secondary explosions that soon turned the carrier into a blazing conflagration.

Likewise, Soryu sustained multiple direct hits, and its flight deck was repeatedly strafed, causing bombs, torpedoes, and fuel to burst into a raging inferno. Lastly, Hiryu was attacked, but this attack had to be rushed, and all bombs missed. Now, dangerously low on fuel, the American flyers had to break-off the attack and return to their carriers.

In only 6 minutes of wild fury, threequarters of the Japanese carrier force had been destroyed. Nagumo, speechless and in a state of shock, watched with tears in his eyes as towering flames engulfed the Akagi.

Hiryu, undamaged, turned into the wind and responded, launching an attack that chased the withdrawing American planes back to the Yorktown, where the Japanese struck with venom. While a valiant defense brought down numerous Japanese aircraft, the Yorktown finally succumbed to a second assault wave, also launched from Hiryu. Stubbornly, Yorktown would not slip under the waves until the 7thof June.

But now it was the Americans turn to counterpunch, Enterprise launching 24 dive-bombers late that afternoon. They soon located Hiryu, penetrated a ferocious ring of protective Zeros, and scored multiple direct hits before departing. The Hiryu, now wildly ablaze, marked the fourth carrier to be destroyed in a long day of incredible aerial combat.

That night both sides jostled for position, expecting combat to be renewed the following morning, but Yamamoto could not relocate the American fleet, and as the horrible scope of Japanese losses became increasingly apparent, he ordered a full withdrawal to the northwest.

As dawn rose on the 5th it was obvious the Americans had won a major, decisive engagement. The Japanese had lost four fleet carriers, 1 heavy cruiser sunk, while another had been severely damaged. The Imperial Navy’s death toll was an astonishing 3,057, while their lost aircraft totaled 248. Moreover, many of their lost pilots and carrier crews were their most veteran, hence difficult to replace.

The Americans, on the other hand, suffered the loss of 1 fleet carrier (Yorktown), 1 destroyer, 307 men killed, and 150 aircraft, many of which had been forced to ditch due to low fuel.

But these lopsided statistics in no way capture the true meaning of the battle’s significance. Had the Japanese taken Midway and inflicted a decisive defeat to the American Navy – as they surely expected to do – the door would have been opened for them to attack Australia, Samoa, and ultimately Hawaii with virtual impunity.

The Imperial Navy would have reigned supreme in the Pacific, extending the war for years. But that did not happen. As a result of Midway, the Imperial Navy lost the initiative in the Pacific, and would be back-peddling for the remainder of the war.

The importance of the American victory at Midway has hardly been lost on historians. John Keegan, for instance, called it “the most stunning and decisive blow in the history of naval warfare,” In six rampaging minutes, the Americans, through skill, heroism, and, yes, a dose of good luck, had destroyed three of the six carriers that had launched the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor (a fourth, Hiryu, would be destroyed later that afternoon), the very attack that had enraged the American people, just six months earlier.

At Midway, the memory of Pearl Harbor spurred many American airmen on to heroic efforts. Because the Japanese high command had no understanding of a democratic society – just as Hitler did not understand the British people – absent entirely from their predatory, Pearl Harbor calculations had been the natural, overwhelming, and unrelenting response of a free people to a blatantly predatory attack.

And as reckless miscalculation is often the offspring of ignorance, the Pearl Harbor strike, while tactically brilliant, would prove strategically suicidal. As military historian Robert L. O’Connell wrote, “Pyrrhus the Epirot would have understood Pearl Harbor. For he learned while fighting the Romans that to win against such an opponent is to lose,” and for Japanese leadership, Midway represented the first chapter of that bitter truth.

Another Article From Us: New Video Uses Veteran’s Account, The Moving Wartime Rescue Story

Jim Stempel is a speaker and author of nine books and numerous articles on American history, spirituality, and warfare. His newest book regarding the American Revolution – Valley Forge to Monmouth: Six Transformative Months of the American Revolution – will be released in October. For a full preview, pricing, and pre-publication reviews, visit Amazon here (https://amzn.to/34J4fZN) Or, visit his website (https://bit.ly/2EAWNVT) for all his books, reviews, articles, biography, and interviews.