It’s a well known and celebrated fact that while the men were off in Europe fighting the Nazis or in the Pacific battling the Japanese Empire, women stepped up and took over the regular social functions normally performed by the men. But, Rosie the Riveter, the WWII icon, aside, this often extended beyond civilian life to include the everyday duties of ordinary military life.

For example, in Hawaii, women took over for the men in office jobs, and took part in night watches, while not far away in Pearl Harbor, the women assisted by taking over all of the motor transport duties, including operating buses, trucks and jeeps.

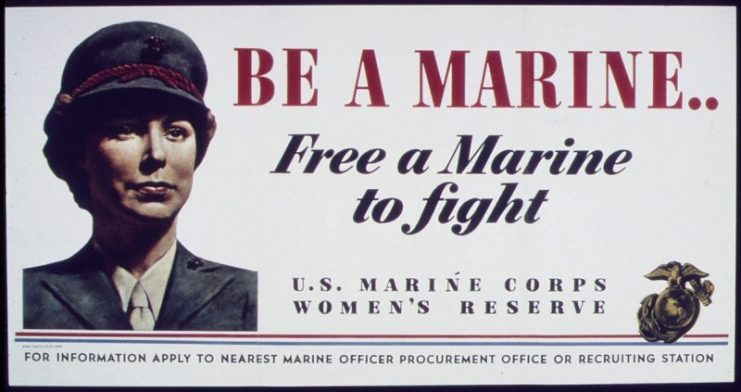

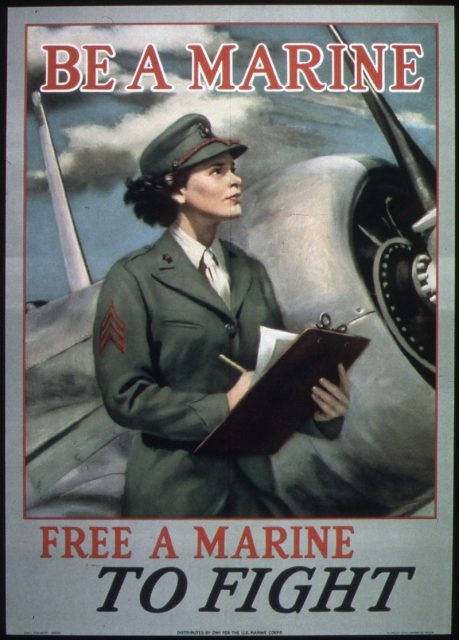

However, little is known about the role that female Marines played in the Second World War. However, author Jim Moran is seeking to change that with his new book US Marine Corps Women’s Reserve. This book details the lives, trials, and tribulations of female Marines in both prose and through a series of color photographs.

Naturally, women faced a number of different social obstacles during their service, including suffering numerous derisive names such as “Marinettes,” the absurd “Femarines” and lastly, the “Women’s Leatherneck Aides.” Colonel L.W.T. Waller, Jr., Director of Reserve did not share these sentiments. “These women will not be auxiliary but members of the Marine Corps Reserve and they will be performing many duties of Marines.”

There are two significant dates dealing with the creation of the US Marine Corps Women’s Reserve. The first is July 30th, 1942, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed a bill into law that allowed for the creation of a woman’s Marine Reserve. The other is February 13th, 1943, when US Marine Commandant Major General Thomas Holcomb announced the formation of a Women’s Reserve.

The law in question allowed not only for the acceptance of women into the reserve at the enlisted level but allowed them to serve as commissioned officers. Their service would last for the war’s full duration and an extra six months after it ended. The intention behind this law was to release both officers and enlisted men so they could engage in combat roles.

To accomplish this, women had to be brought in to fulfill the roles left vacant by the men’s absence. To fill this gap, between 1943 and 1945 American women enlisted in the thousands, thus allowing men the ability to get fully involved in the fighting.

Of course, acceptable candidates for induction had to meet a few requirements, such as they had to be American citizens, not be currently married to a Marine, and not have any children under eighteen years of age. By the end of the war, the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve had recruited more than 18,000 women.

Jim’s fascination with the history of the Marine Corps has lasted for forty years, and his expertise has been utilized by Hollywood twice, with the films Flags of Our Fathers and The Pacific.

‘This book is intended to highlight the little known major contribution made by women Marines who, whilst not being front-line, fighting Marines, carried out the vital support functions which freed the male Marines to fight. There is little reference material available on this subject and my long association with Marine Corps veterans, including women Marines, identified the gap.”

One of the stories showcased in the book is that of Lillian Marie Sandy, whose assignment to Motor Transport School after joining the Reserve taught her both the mechanics and operation of trucks.

She went on to serve as an assistant driving instructor while stationed at Pearl Harbor before she was transferred to the Marine Air Base in 1945. She would later meet her husband while serving in the Reserves and remained married for sixty-seven years before passing away in 2009.