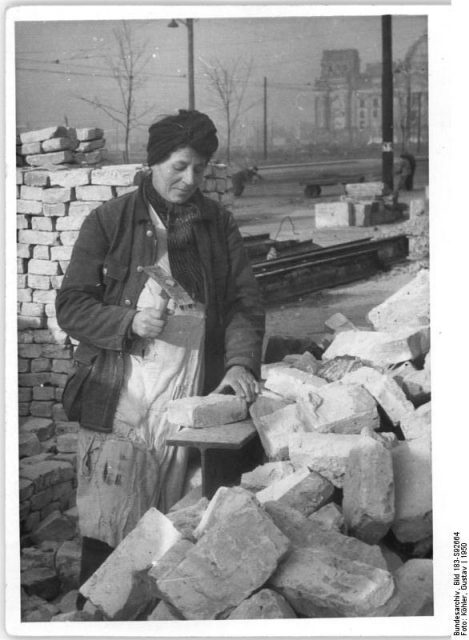

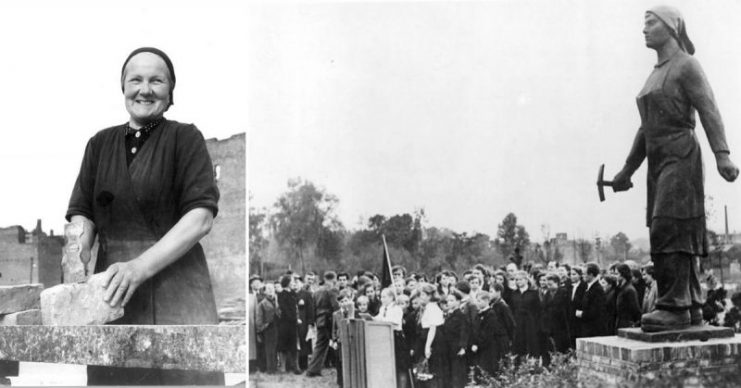

Throughout Germany, there is a repeated motif in statues: A woman, with a hammer in her hand, her hair pulled up in a kerchief, looks determinedly into the distance. The statues are monuments to the Trümmerfrau (“rubble woman”) who is revered in German history for her help in rebuilding the country after World War II.

In the early part of the war, the Germans rained bombs down onto Britain in what has become known as “the Blitz.” At the end of the war, the Allies repaid in kind by dropping tons of bombs on German cities, reducing great swaths of major cities and other urban areas to rubble.

In May 1945, it is estimated that German cities lay under 400 million cubic meters of rubble. If you piled that much rubble onto ten soccer fields, the pile would be the same height as Montblanc – the top being permanently snow-covered.

In Hamburg alone, 50% of the housing was completely destroyed. Only 25% escaped the war without damage. In the days after the fighting ended, the city had to find some way to remove 43 million cubic meters of rubble.

In 2005, when German Chancellor Helmut Kohl dedicated a statue to the Trümmerfrau, he said that it “commemorates the large number of women who volunteered to clear the ruins.” Since then, the symbol of women cheerfully volunteering to clear out the damaged cities to make way for the rebuilding of Germany has been reinforced over and over in the German public spaces.

But historians are now pushing back against this idea. Leonie Treber calls the story of the Trümmerfrau a “legend.” Not only was there not a particularly large number of women involved in the clearing of the rubble, the ones that did help were not there voluntarily.

Treber started her research into the Trümmerfrau in 2005. She wrote her doctorate at Duisburg-Essen University about them. Before that, the subject had not been studied academically. She has recently published a book based on her research called “The Myth of the Trümmerfrauen.”

According to Treber, the role that women played in clearing out all of that rubble was minor. In Berlin, 60,000 women worked to clear rubble, but that was less than 5% of the female population of the city.

Not only were the women not volunteering to help in the rebuilding, the men weren’t signing up either. It was not seen as honorable to help rebuild. In fact, it was considered punishment.

The reason for that lies in the fact that the Nazi party forced soldiers, Hitler Youth, prisoners of war and concentration camp prisoners to clean up the rubble in Berlin during the war. After the war, the authorities began using prisoners of war and former members of the Nazi party. Only when progress was insufficient using those forced laborers did the country turn to the general population for help. In the West, the help was voluntary. In the Soviet-occupied territory, the population was forced to help.

Berlin encouraged participation by making the second-highest category of food ration cards available to the Trümmerfrauen. They showed images of smiling women cheerfully lugging stones and bricks. The image was repeated so many times, it is ingrained in the German collective consciousness.

This campaign originally only worked in East Germany where the Trümmerfrau ideal became the role model for women seeking traditional male work. In the West, though, the image didn’t line up with conservative views of a woman’s role.

In the 1980s, the image of the Trümmerfrau returned to West Germany, this time as one of the heroes of the German reconstruction when politicians were arguing over providing benefits for women born before 1921.

Since then, the image of the selfless German woman, happily toiling to rebuild her homeland, has been unassailable in the German public eye.

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

Treber concurs that these virtuous women existed. It’s just that they were in the minority.