Rain began falling in sheets as the small steamer known as picketboat No. 1 puffed its way through the choppy surf toward the mouth of the river, now just minutes away.

Directly astern, the boat tugged an open cutter full of sailors, all hand-picked, good with “revolvers, cutlasses, and hand-grenades.”

The two boats had departed the Shamrock almost three hours earlier, and now, as the mouth of the river loomed ever-nearer, their sense of casual confidence gave way to grim determination. For they had all volunteered for a mission many senior officers in Washington considered suicidal.

It was October 27, 1864, and the cold, rain-drenched men were slowly departing Albemarle Sound for the Roanoke River.

They were still about ten miles from Plymouth, North Carolina, where their objective – the Confederate ironclad ram, CSS Albemarle – was berthed amongst an array of elaborate defensive measures. Every man realized he was in for a long, dangerous night, and that many would not be returning.

Their task was to either cut the ironclad out or, if that proved unfeasible, torpedo the Albemarle in its berth. Not one man had the slightest notion that within days the New York Times would hail their mission as “one of the most daring and romantic naval feats of history.”

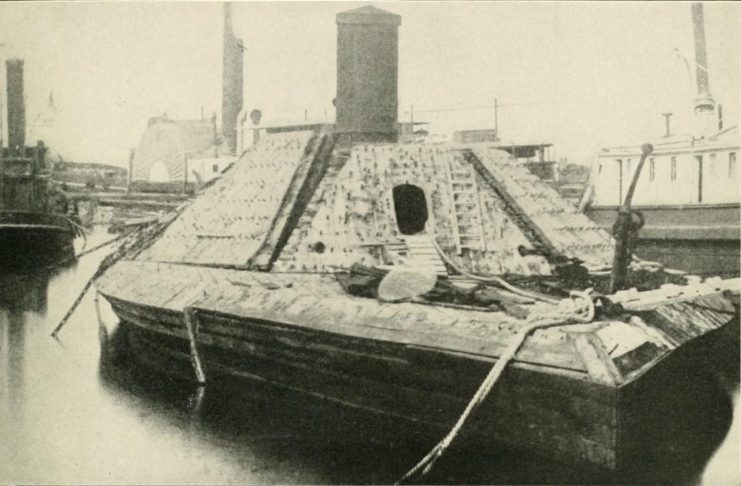

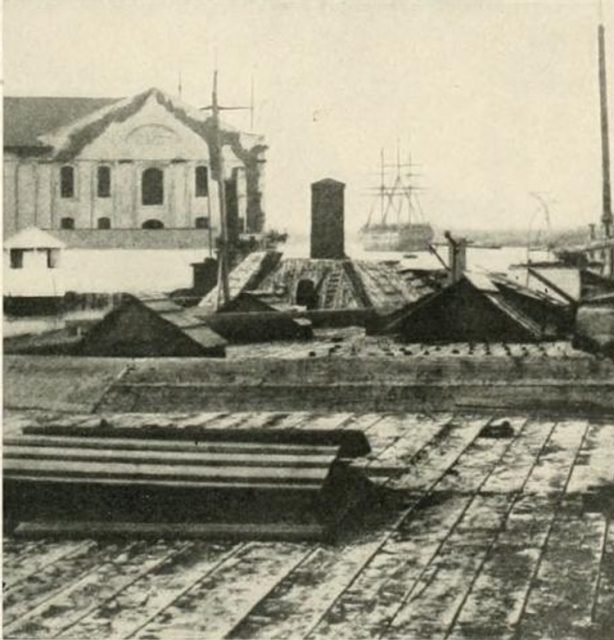

In April of that year the recently completed Albemarle had descended the Roanoke to surprise, then drive-off a small Federal flotilla patrolling near Plymouth and spearhead the Confederate recapture of the town.

Then in May the Rebel ram appeared on the open waters of Albemarle Sound, bound for New Bern, North Carolina. She was promptly attacked by a flotilla of seven Federal gunboats, large and well-armed, sixty naval guns against the Albemarle’s two.

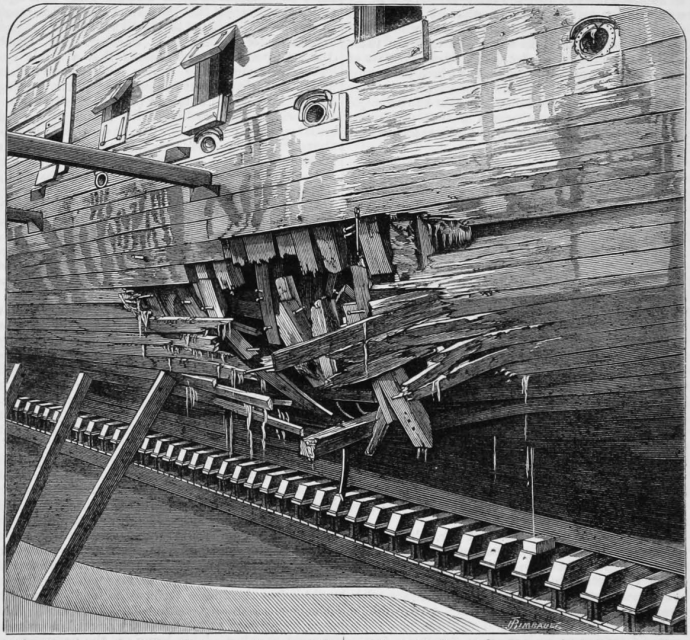

For hours, the battle raged, the Federals surrounding the Confederate vessel as it bobbed about between them, blasting away at virtually point-blank range. When it was all over, the Federals had hurled 557 rounds at the ram, but accomplished little more than riddling its smokestack, shaking loose a few iron plates, and damaging the tube of one naval rifle.

The Federal flotilla, on the other hand, had suffered severely, experiencing damage to every vessel, much of which would require months to repair, even though the Albemarle had fired only 27 shots.

Because of the Albemarle’s shallow draft, the powerful Federal monitors could not gain the sounds and challenge her on inland waters, creating in turn a serious problem.

For if the Albemarle was allowed to dominate the sounds unchallenged, it would open all of North Carolina again to blockade runners, thus reopening supply routes to Richmond, and extending the duration of the war. President Lincoln bristled at the thought of an extended conflict, so something else, something drastic, had to be done.

But, so far, every attempt to sink or damage the ram had failed, thus in sheer desperation the navy finally turned to a twenty-one-year-old lieutenant named William Barker Cushing. Cushing had already established a long record of special operations style hit-and-run raids along the South Atlantic coast, becoming something of a legend in the Navy even before his twenty-second birthday. But taking on the Albemarle seemed, to many at least, beyond even Cushing’s unique capabilities.

The Roanoke was picketed, for instance, from Albemarle Sound, clear to Plymouth, and a heavily armed schooner along with an artillery piece established on a wreck in mid-channel awaited anyone who journeyed upriver.

At Plymouth, a full brigade of infantry had been deployed to protect the ram, and a battery of artillery unlimbered at water’s edge to sweep all approaches. The ram’s two Brooke rifles were also reported to extend over the river, capable of blasting any approaching craft to smithereens. Numerous illumination fires had been erected, and the picket posts had warning rockets at their disposal. A successful approach appeared impossible.

Yet the ram still had to be destroyed, so now Cushing and his party were puffing up the narrow channel in the pouring rain, the small steamer’s engine recently muffled to reduce noise. The men hunkered low, complete silence an absolute necessity. There were fifteen men in the steamer, another thirteen in the cutter, all shivering in the cold, driving rain.

Around 2:30 AM they approached the wreck and schooner in mid-river, and every man cautiously reached for their weapons.

Suddenly, the schooner emerged from the mist like a phantom, so abruptly, in fact, that Cushing had little choice but to try and slide by on the shore side. Literally holding their breath, the men in both boats slipped past undetected, so near the schooner that the conversations of the Confederate pickets onboard were clearly audible.

Exhaling as the boats rounded the next bend, in another ten minutes the party neared Plymouth, where the ironclad’s silhouette was spotted against the southern bank. Cushing still hoped to cut the ram out, so he headed past the ironclad toward a small wharf where he might put in.

But suddenly a sentry atop the Albemarle turned and called out: “Who goes there!” Then again: “Who goes there!” They’d been spotted!

Boarding the ironclad was now impossible, so Cushing dropped the line to the cutter, ordering those men to go back and take-out the schooner they’d passed downriver. Then he headed in toward the ram but instantly noticed something bobbing in the water.

He pulled alongside – it was a log apron, guarding the ram. Shots began to ring-out, slapping the water. Enormous illumination fires leaped to life along the water’s edge, turning night into day. A siren sounded. Guards began running, shouting, shooting. The back of Cushing’s coat was blown-away by a shotgun blast, the sole of one shoe shot-off.

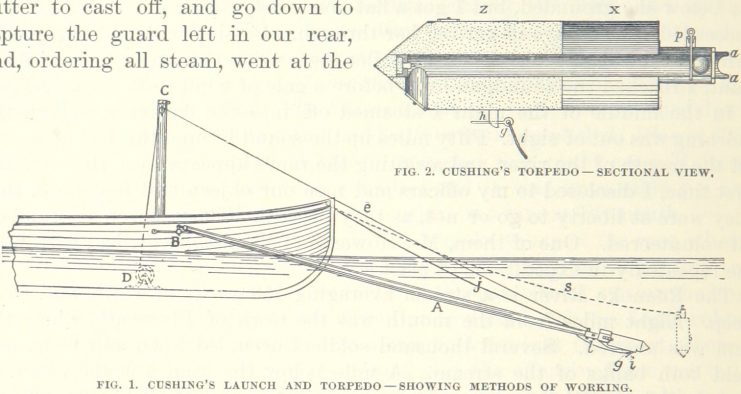

Back into the shadows Cushing steered the picketboat, recalculating his attack on the fly, focused now upon one desperate effort. He intended to gain enough speed to jump the log apron, then slip into the water near the ram.

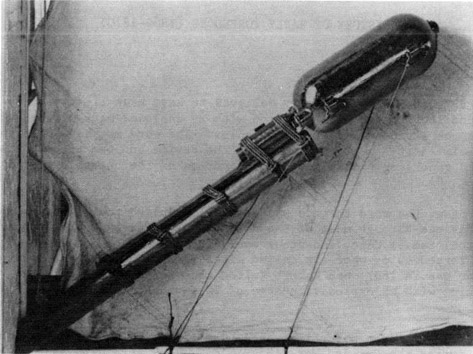

If successful, he would extend the spar torpedo and blow a hole in the Albemarle before the guards could respond. It meant he and his men would have no avenue of escape, but escape was no longer a consideration.

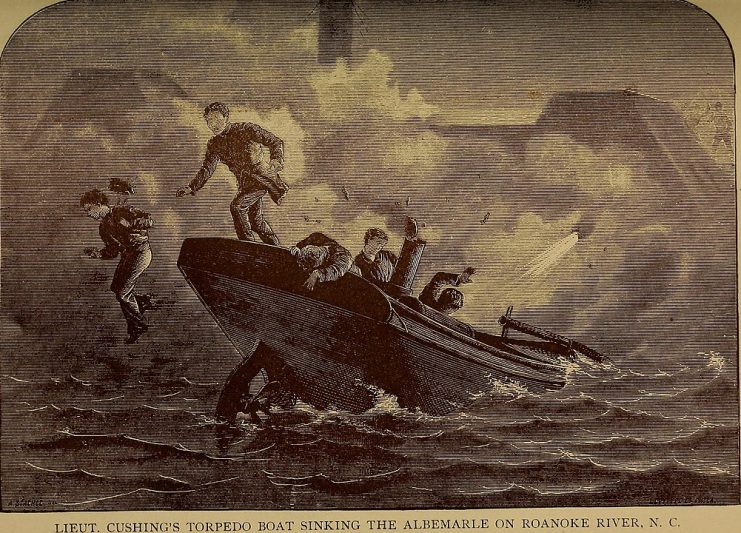

With bullets ricocheting off the steamer and roiling the water around them, the boat struck the apron at full speed, bouncing into the air, then tilting forward into the pen with the Albemarle.

There was no time to lose. An officer pushed the spar deep into the water, but detonating the torpedo was a tricky affair. Once the spar had been advanced, Cushing had to wait for the torpedo to gain depth. Then he had to tug a release line, allowing the torpedo (something akin to a modern mine) to drift up under the target, before finally pulling the trigger line. If the entire sequence were not executed precisely, the torpedo would not detonate.

Now bullets were flying all around him, and his men were screaming, falling, dodging for cover. One of the Albemarle’s enormous Brooke rifles stared Cushing almost directly in the face, and he could hear the commands of the Confederate gun crew inside as they cranked the barrel lower. He had only seconds before the gun fired, atomizing him in an instant.

A bullet creased his neck. Four more ripped through his coat. Still, Cushing refused to budge, but worked calmly, finally releasing the torpedo, then counting coolly to ten, allowing the torpedo to float-up under the ram, all this as hell broke loose around him.

A fifth bullet sliced his hand, then another tore away his collar. Inside the ram the Confederates were preparing to fire the Brooke just as Cushing finally counted “ten” and tugged the trigger cord.

An enormous explosion ensued. The steamer dipped momentarily as a gigantic plume of water rose high above the ram, then collapsed, swamping Cushing, his men, and the steamer at once.

The torpedo and the Brooke had gone off virtually simultaneously, the shell from the naval gun passing just over Cushing’s head. For a moment everything was still, both sides numbed by the violent detonations. Then the Rebels began firing again, and Cushing yelled for his men to “save yourselves,” as he tossed his coat, sword, and shoes aside, diving off the stern.*

The cold water stunned him awake, and he swam for his life as bullets stabbed the water. Soon there were search boats out looking, their lanterns illuminating the surface, so he dove each time they neared, holding his breath to avoid them.

The current began taking him south. He surfaced and swam and swam until cold and exhaustion at last overwhelmed him, and – physically overcome – he finally sank like a stone. But, drifting low, Cushing felt mud in his hand. Frantic, he pulled at the muck, yanking himself forward, discovering the riverbank. He clawed his way up. Utterly exhausted, he took a few steps forward, then collapsed into the mud, unconscious.

As the sun rose, Cushing awoke, directly under the nose of a Confederate palisade. Carefully timing his movements, he slid across the riverbank to the thick vegetation of the Carolina swamp nearby. There he located a slave whom he paid to go inspect the Albemarle, and minutes later the man was back telling him that the ram now rested on the bottom of the river – the torpedo had done its job!

The slave also pointed the way south through the swamp, so Cushing took off on foot, dodging search parties everywhere.

For hours he beat his way through brush and creeks, tearing his feet to shreds on stickers and thorns, before finally stumbling upon a farm road. Getting his bearings, he headed south, tracking blood across the dirt, until coming upon a Confederate picket post around dinnertime.

The Rebels had a skiff tied-up in a creek that emptied into the Roanoke, so Cushing dodged tree-to-tree, until the Confederates sat down for dinner. Then he slipped into the water, untied the skiff, and quietly pushed it out toward the channel.

He rolled into the boat, picked up a paddle, and began paddling with what little energy he had left. Soon darkness and mist enveloped him. Cushing fought against exhaustion for hours, paddling until he finally gained Albemarle Sound, then labored hours more out into the widening waters.

At last he spotted the running lights of what appeared to be a Federal patrol boat. Cupping his hands around his mouth, he hollered with everything he had left: “Ship Ahoy!” Then he collapsed unconscious into the bottom of the skiff.

Fearing a Rebel attack, a cutter was sent out from the Valley City to carefully reconnoiter. Finding Cushing alone, they tossed him into the cutter, and rowed back. With his uniform half-shot away, covered in mud, blood, and reeds, no one had any idea who, or what, he really was.

So, still unconscious Cushing was tossed unceremoniously onto the deck of the Valley City as a crowd gathered round for a look. Fortunately, the City’s skipper, J.A.J. Brooks, knew Cushing, and fell to his knees for a closer inspection. “My God, Cushing!” he cried, “is this you?” Cushing came-to, identified himself, and told Brooks of the Albemarle’s demise. The crew exploded in wild cheers.

Cushing was promptly bathed, attended to by the ship’s surgeon, then rowed to the Shamrock, the fleet’s flagship. News of his success and epic ordeal had already been flashed throughout the fleet, and their response was beyond jubilant.

In a scene that could have been written in Hollywood, crews cheered, ship’s whistle’s peeled, and rockets were thrown up like the 4th of July, as Cushing stood by the rail and drank it all in. It was an incredible end to an incredible mission.

William Barker Cushing would go on to post one of the most remarkable wartime records of daring and success ever achieved by any officer in the United States Navy. It was Admiral David Farragut, after all – who knew a little something of heroism himself – who once remarked that “young Cushing was the hero of the war.”

On November 3, 1864 the New York Times wrote: “The destruction of the rebel ram Albemarle by Lieut. Cushing proves to be one of the most daring and romantic naval feats of history,” and today, some 156 years later, it has lost none of its luster.

Civil War Cannonball Exploded & Killed 140 Years After it Was Fired

*Only Cushing and one sailor escaped. Two of the steamer’s crew were killed, the other eleven taken prisoner. They were removed to Libby Prison in Richmond, later paroled on February 21, 1865.

By Jim Stempel

For a full list of his current books, please click here: amazon.com/author/jimstempel

For a preview of his newest Revolutionary War book, due out this fall, and a full listing of his other works, simply click here: https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/PDhuzQEACAAJ?hl=en

Jim Stempel is the author of numerous articles and nine books on American history, spirituality, and warfare. His most recent book, American Hannibal: The Extraordinary Account of Revolutionary War Hero Daniel Morgan at the Battle of Cowpens, is currently available at virtually all online booksellers.