Historian Martin Mace was researching the British Special Operations Executive in government archives when he came across a report that had lain unread for 74 years. He was soon engrossed reading about the real details of what happened during the infamous Great Escape from the Stalag Luft III Prisoner-of-War camp at Sagan in Poland. Mace used the report as a basis for his recently published book, Stalag Luft III, An Official History of the ‘Great Escape’ PoW Camp. The report was written from accounts supplied by 26 of the escapees.

The book gives a fascinating insight into life inside the camp. It tells how the Germans administered the prison, along with details about the Planning Committee – the brains behind the planning and execution of escapes. The reader is held intrigued by aspects of life inside the camp, as well as how morale was kept high among the prisoners.

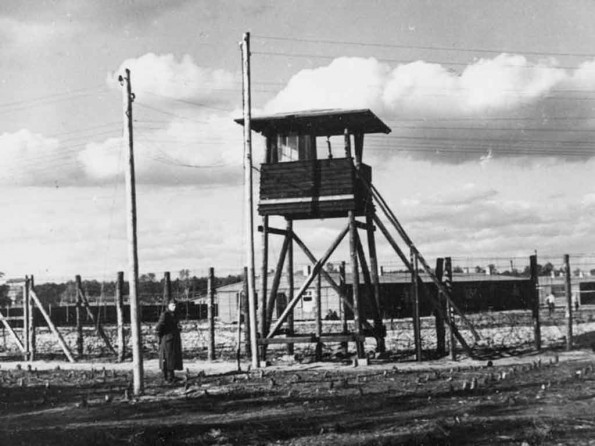

Stalag Luft III had been built with all the prisoners’ accommodation raised on stilts to prevent them digging tunnels. It did not stop the men incarcerated there; they dug over 100 meters in sandy soil to create three tunnels, named Tom, Dick, and Harry.

The plan was that on the night of March 24/25 1944, two hundred men would escape into the forest around the camp by crawling through the tunnel named Harry. Unfortunately, only 76 men made it through before guards detected their escape. Of them, only 3 made it all the way to safety. In a fit of rage, Hitler ordered the Gestapo to shoot 50 of the recaptured escapees.

One incredible story was recounted by Lieutenant Neely, who was number 28 out of the tunnel. He described how he made his way to Berlin, where he wandered around under the noses of the Germans, before catching a train to Stettin, late in the afternoon. He arrived there early in the evening and booked into a hotel where he spent the night. The next morning, he went to the address he had been given before escaping from the camp, 16 Klein Oder Strasse. When the door was opened, it was obvious he was at the wrong place and should have been at No 17, next door, which was a brothel. He left the area, and after enjoying lunch at a restaurant, he returned to Number 17 but was informed they could not help him and that he had to wait for a Swede.

By late in the afternoon, Neely was getting nervous and left the brothel. He spoke with a man in the street, who took him to a friend who worked in the kitchen of a hospital. Neely hid in the hospital, protected by three men working there, for two nights and a day. Neely hid during the day, and at night went out to try and locate the Swede who could help him. There were no Swedish boats in the harbor, but a Frenchman working on a tug there undertook to let him know when one arrived. Unfortunately, he was recaptured before he could board a friendly ship.

Perhaps more interesting was the detail around the work of the Escape Committee, based in the camp and headed by Squadron Leader Roger Bushell of the RAF. The committee aimed to vet all escape plans thought up by the prisoners. Each committee member had experience with various types of escape; tunnel, transport, over the wire or through the gate.

A committee member would undertake the first interview. If he thought the plan had promise, he would assist the prisoner with fleshing out the idea into something workable and then provide everything required such as forged documents, maps, contact details, clothing, etc.

Bushell would brief the escapee just before the actual attempt. He was given a cover story and instructed not to reveal the workings of the Escape Committee should he be recaptured.

The committee also debriefed all escapees if they were recaptured. They provided a wealth of information on documents required, clothing styles, problems with travel, regulations they found when booking into a hotel, how food coupons were used and what contacts had proved reliable.

The Hollywood movie, starring Steve McQueen as Captain Virgil Hilts, Richard Attenborough as Squadron Leader Roger Bartlett and James Garner as Flight Lieutenant Robert Hendley, was based on a book written by Paul Brickhill. There were no American prisoners involved in the escape, and the motorcycle race to the border, with all its dramatic stunts, never took place. It was included in the movie at the request of McQueen.

The story of life in the camp, the meticulous planning by the Escape Committee and the Great escape itself, needs no embellishment. It is a tale of courageous men who were placed in an extraordinary situation and rose to exceptional heights as a result.