Commemorations of both World War One and World War Two are, in the main, focused on remembering the efforts and sacrifice of the troops. Women are usually remembered for their role as nurses and carers for the sick and wounded, or as widows whose husbands had been killed in action.

Now a new museum is to open in Scotland to commemorate the work of the ‘Canary Girls’. The Canary Girls, as they were known, were young women who worked in British munitions factories during the war. Their work ensured that the troops on the frontline would have a continuous supply of ammunition to fight the enemy.

The name ‘Canary Girls’ was given to them because their skin would turn yellow if they came into contact with sulphur.

At the outbreak of the war private companies were supply Allied troops with munitions, but the government could tell that what they could produce wasn’t going to be enough to support the growing war effort. David Lloyd George became munitions minister in 1915, and implemented the Munitions War Act, which ensured that ammunition production would be increased to meet demand.

While the majority of young men had been called up for service, the government turned to Britain’s young women, encouraging them to sign up for work at the munitions factories. By this time there were both private factories that the government was managing, as well as new factories that the government had established itself.

In total, there were more than 4,000 factories producing and supplying ammunition by the end of the war.

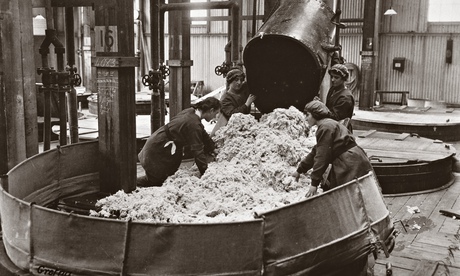

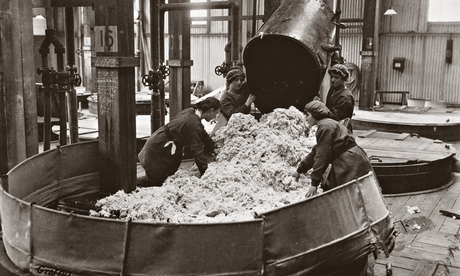

The largest factory was in the south of Scotland, called HM Factory Gretna. It produced cordite, which is an intricate compound of explosives used for gun cartridges. The mixture actually released gases that forced the bullets and shells out of the weapon. Its ingredients were highly toxic and the method of making the mixture was hazardous, so the different stages of production were separated into different parts of the factory.

The factory drew thousands of women to work there and a community with new houses, shops and facilities sprung up in the surrounding area. Three years into World War One and the factory was producing around 800 tonnes of munitions every week.

In one notable visit, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, author of the Sherlock Holmes mysteries, was amazed at the extent of the facilities, and praised their work, as well as noting the good community services.

Most of the women were from a working class background and came from being domestic servants or working in shops on the high street. Historians show how their lives were tough, with long working hours, one day off per week and limited access to nearby towns or trips to see their families. The majority of the women’s accommodation was in large huts with living areas and furniture made of wood. Records show that the intense Scottish winters were extremely hard to bear for the women.

The female workers were promised the same wages as male workers.They earned around 30 shillings to £2 per week with deductions for accommodation and food. Security was tight and the women were searched to ensure they had no accessories on their person that could potentially be dropped into or mixed with the explosives, such as pins and hair clips.

The toxic vapours from the chemicals would cause illness, and many would faint or fall asleep at work due to the fumes. It is estimated that there were around 300 deaths at the factories, The Guardian reports.

Once World War One ended, the factories were closed and unfortunately women took second place to those male troops who were returning home and looking for work. The work of the women was no doubt looked upon positively by the women’s suffragette movement. In 1918 women at and above the age of 31 were given the vote. However, most of the workers were young women below this age, and so could not vote at this time.

Now, a new museum opened at Eastriggs, near the HM Factory Gretna to remember the work of British young women who supplied the munitions and to tell their story.