Historians have long surmised that Richard M. Nixon, the presidential contender in 1969, interfered with peace talks to end the Vietnam War, to bolster his campaign.

Recently discovered notes written by H.R. Haldeman, who became Nixon’s White House chief of staff, showed that during a telephone conversation with Nixon, he was instructed to continue ‘working on’ South Vietnamese leaders to coax them not to agree to a settlement in peace talks that would possibly end the Vietnam War before the election in 1968.

Nixon, as the Republican candidate, was sure that President Lyndon Johnson, who didn’t seek re-election, was purposefully attempting to disrupt his campaign with a politically motivated peace effort meant to enhance the candidacy of Vice President Hubert M. Humphrey.

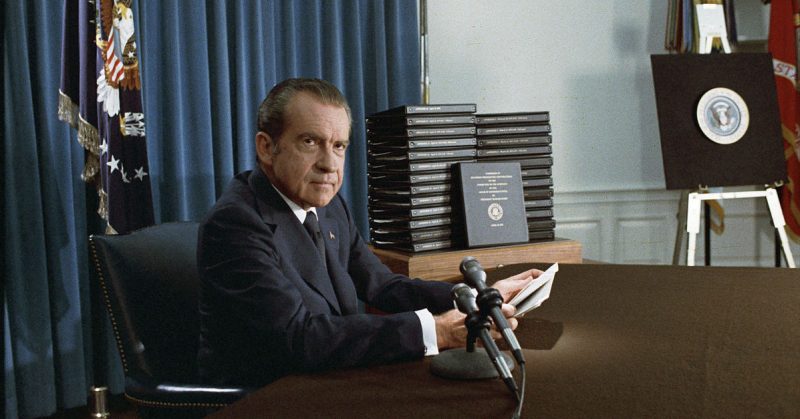

There’s little doubt interfering in the peace talks were a step beyond the norm. This was likely more serious than anything he did in Watergate, said author John A. Farrell. Farrell found Haldeman’s notes during his research at the Richard Nixon Presidential Library for his upcoming biography of Nixon, to be published in March.

Throughout the campaign, Nixon loyalists kept a secret communications channel open to the South Vietnamese leaders using Anne Chennault, widow of Claire Lee Chennault who led the Flying Tigers during the Second World War. She had become a notable Washington hostess and Republican fund-raiser. She was the channel for encouraging the South Vietnamese to wait for a better outcome under Nixon. Understandably, Johnson was enraged when he learned of Nixon’s machinations.

The notes unearthed by Farrell originated from a phone call on Oct. 22, 1968. Johnson was ready to order a pause in the bombing to promote peace talks in France. Haldeman wrote down what he was told by Nixon, ‘Keep Anna Chennault working on SVN,’ referring to South Vietnam.

Later, he wrote that Nixon wanted Illinois Republican Senator Everett Dirksen to contact the president and discredit the proposed bombing pause. ‘Any other way to monkey wrench it?’ Haldeman wrote. ‘Anything RN can do.’

Moreover, Nixon added later, that his vice-presidential running mate should talk with Richard Helms, director of the Central Intelligence Agency, and threaten him with termination in the new government if he refused to furnish additional insider information.

After resigning from the presidency, Nixon denied knowing about Mrs. Chennault’s role in passing messages to the South Vietnamese in the 1968 campaign, even though there was proof she had been in contact with Nixon’s campaign manager, John N. Mitchell, who later became attorney general.

Researcher Ken Hughes at the Miller Center of the University of Virginia, author of ‘Chasing Shadows,’ a book exploring the episode, published in 2014, said Farrell had discovered a smoking gun.

This appears to be the missing element of the puzzle in the Chennault matter, he said. The notes verify that Nixon perpetrated a crime to emerge victorious in the presidential election, The New York Times reported.

Scholar Luke A. Nichter at Texas A&M University, one of the leading students of the Nixon White House secret tape recordings, doesn’t agree with the conclusions about Haldeman’s notes. From his perspective, they don’t provide any new information and are too weak to make larger deductions.