“Hang Him” and “Remember Andersonville” were epithets screamed by former Union prisoners of war at the hanging, on 10th November 1895, of one of America’s most notorious and controversial civil war criminals. So who was this devil in disguise? He was Heinrich Hartmann Wirz, better known as Henry Wirz, the commandant of the notorious Confederate concentration camp, Camp Sumter, or Andersonville as it was known to Union soldiers.

Henry Wirz was born on the 25th of November in 1823 to Caspar Wirz and Sophie Barbara Philip in Zurich, Switzerland. He was educated to secondary school level and dreamed of becoming a doctor, but his parents could not afford the medical school fees, so he became a merchant. In August of 1845, he was sentenced to four years imprisonment for failing to pay his debts, but was given the option of having his sentence commuted to twelve years of enforced emigration, which he chose.

Wirz went first to Russia in 1848 and then in the following year he moved on to the USA where he held several positions, ending up in Louisiana where he worked as a plantation overseer and doctor near Fort Levin.

At the outbreak of the Civil war in May 186, Wirz enlisted into the Louisiana Volunteers as a private in Company A, of the 4th Battalion. After losing the use of his right arm due to a battle injury, he was promoted to captain, with his promotion based upon “bravery on the field of battle”. He could no longer fight on the front lines, so he was attached to the staff of General John Winder, who was responsible for all the Confederate prisoner of war camps.

After undertaking a diplomatic mission to Europe on behalf of the Confederacy, he was sent to Alabama as a prison guard. In February 1864, the Confederate government established Camp Sumter and in April of that same year Wirz took command of the camp. He was there when just before the end of the war he was promoted to Major.

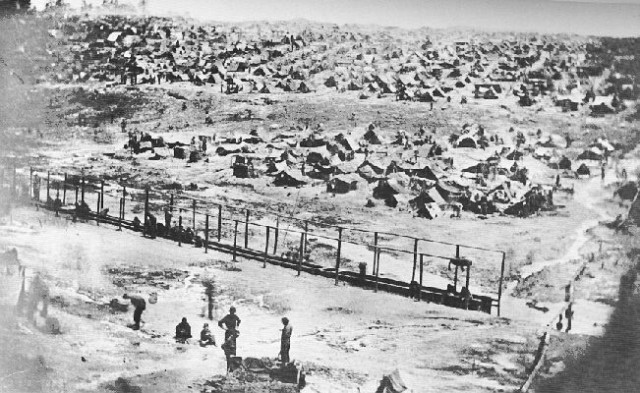

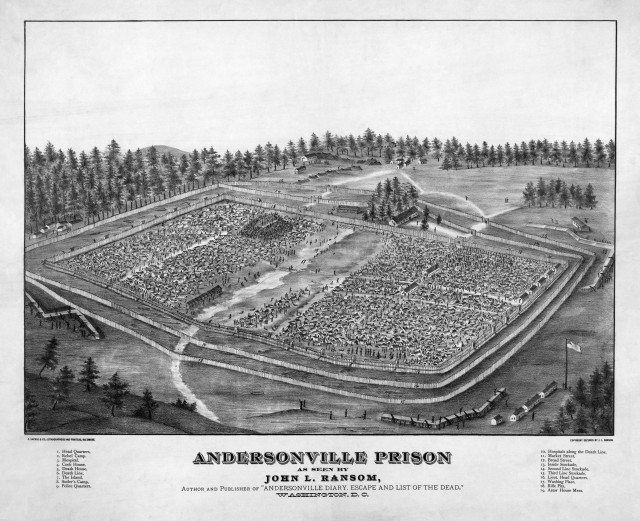

Any war fought between the peoples of one country is bound to be an especially brutal affair, especially when pitting brother against brother. From all accounts, Camp Sumter, or Andersonville, was an especially brutal place. This prison began life as a stockade built on a dusty plain with a small stream, Sweetwater Creek, running through the camp. It was planned to build barracks, but they never materialized, and the Union captives lived in shanties or rude huts sometimes called, “shebangs” – dismal shelters built with whatever was at hand, usually old blankets and a bit of wood from packing cases.

These shelters neither kept the sun off in summer nor protected against the cold in winter. Sanitary facilities were non-existent, and the stream that was supposed to provide drinking and washing water soon became clogged with human waste. The banks were decimated by hundreds of feet, turning the area in one, large marshy mess. The food was scarce, and the guards regularly kept food from the prisoners as a form of punishment.

Any slight infraction of the rules resulted in the prisoner being shackled to a ball and chain; if an escape did occur, guard dogs were used to run the prisoners down. The stockade was designed to hold 10,000 prisoners but by August of 1864, it was home to almost 31,000 men. Thousands perished in the inhumane conditions.

At the end of the war, the Union Army was horrified by what was found. Walt Whitman, the war poet, wrote, “There are deeds, crimes that may be forgiven, but this is not among them.” Wirz was still at his post when he was arrested by US Cavalry Captain Henry Noyes in May 1865, and he was transported to Washington to stand trial. He was indicted for murder and conspiracy to injure the health and lives of Union soldiers. There were many strange outcomes of this trial, but the biggest inconsistency was that both the prosecution and the defense both tried to prove that Wirz was only following orders.

The prosecution hoped that this trial would lead to trials for higher-ranking Confederate soldiers, and the defense wanted to move the blame from Wirz to someone further up the chain of command. His defense of “following orders” was rejected and he was held accountable for his own brutal behavior. After a two-month trial, during which 160 prisoners testified, he was found guilty and sentenced to hang. Reportedly, on the scaffold, he said to the officer in charge, “I know what orders are, Major. I am being hanged for obeying them.”

Following the trial, several issues arose, with the most serious being the testimony offered by a man by the name of Felix de la Baume. De la Baume gave evidence that he had personally witnessed Wirz murdering an inmate. He was a charismatic man who spoke well; he so impressed the trial commission that he received a written commendation on the quality of his testimony.

Based upon his trial testimony, he was granted a job within the Department of the Interior. Eleven days after Wirz was hung, de la Baume was unmasked as Felix Oeser, a war deserter, who had fled from the 7th New York Volunteers. Oeser admitted that he had perjured himself during his testimony at Wirz’s trial.

Wirz’s hanging still has the power to polarize Americans to this day. To the North, he was a butcher and evil personified but to the South he was a man doing his job under impossible circumstances; he was made a scapegoat by the hysterical ranting of the Union leadership. In Wirz’s defense, he was working under almost impossible conditions.

The camp was deliberately situated for the following reasons:

- It was in central Georgia and therefore far from the Union lines, there was a railway nearby (the Georgia South Western Railroad),

- There was plenty of water as there was a stream running through the site, pine forests surrounded the camp, so there was a plentiful supply of wood for building the camp as well as providing fuel for cooking and heating,

- The closest town had a population of twenty so there would be little resistance to the site of the camp, and, lastly, the local landowners owned slaves that could be pressed into service to build the camp.

Construction on the camp started in December of 1863, and two months later six hundred prisoners arrived from Libby Prison in Richmond. The camp was far from finished, and one wall of the stockade was missing altogether, so artillery guns were pointed at the opening to deter escape. When completed, the stockade consisted of pine logs standing twenty feet high surrounding a rectangular space that measured just over sixteen acres. The camp was designed for 10,000 prisoners. As most prisoners were exchanged, this camp was intended as a type of transit facility – holding prisoners until their exchange could be arranged.

This all started so well, but what changed? Many problems arose with food. The farmers in the area did not want to deal with the military, which was forced to buy at fixed prices and in near-to-worthless Confederate currency. Also, many of the large plantation owners were not prepared to grow food; they continued to plant cotton, which drove the prices of food in the area sky-high. In an effort to drive the food prices down and to feed the inmates of the camp, a tithe was placed on all food production whereby 10% had to be given to the military. This infuriated the local barons, who saw it as a step too far by the Confederate Government and directly against what they were fighting for.

By mid-1864, it was almost impossible for the camp to purchase or demand any supplies, even if supplies had been available. Close to one million pounds of cornmeal was required each month to feed the inmates – an impossible task at the time. The camp was in a similar position about trying to purchase timber to warm the barracks and to burn in fires. The ship building yards in Columbus were paying considerably more for cut and dressed boards, and the camp was again constrained by the price-fixing policy of the Confederate government.

This meant the camp could not compete with the ship yards, so the timber went there instead of to build the camp. There were food and timber available, but the camp could not access it as they could not pay market prices. Anecdotal evidence from the area tells of warehouses full of food and lumber that the owners would not sell for anything other than gold, directly undermining government edicts.

In June of 1864, the Union halted its program of exchanging prisoners because they believed that the practice was reinforcing the Confederate ranks and because the Confederate army would not exchange black prisoners. The North insisted that negroes were part of the exchange, but the Confederate General Lee claimed that Negroes belonging to Southern citizens were not eligible for exchange. This had a critical impact at Andersonville. The population of inmates rose to nearly 30,000, food was in short supply, there were no barracks, and the water supply was polluted. To alleviate the overcrowding, the camp was expanded to just over 26 acres, but it did not help much.

None of Wirz’s appeals to the Confederate Government for assistance were answered, and General Winder was of the opinion that all Union soldiers deserved to die – if that happened at the camp instead of on the battlefield, he would not be sorry. The Confederate military was impoverished and could not supply their troops with rations, so the possibility of providing enemy soldiers with supplies was very low on their list of priorities. As the Union Army pushed towards the sea, General Sherman used a scorched-earth policy whereby anything from food to railways that could assist the South was systematically destroyed.

This push meant that Wirz lost all his regular army guards, as they were called to the front and he was left using local militiamen as guards. This greatly increased the possibility of escape for the Union soldiers, so Wirz instituted a line of pine logs which ran around the camp approximately twenty-five feet from the palisade. Any prisoner crossing the line of logs was shot on sight and artillery was trained at the Palisade to deter further escapes and to ensure no uprisings inside the camp were attempted.

All of these problems contributed to the state of misery inside the camp – fresh food was unobtainable, scurvy broke out along with dysentery from the polluted stream, and gangrene was common in untreated wounds. The conditions were so appalling that Wirz paroled five Union soldiers and sent them to the North to try and get the prisoner exchange reinstated, so as to try and lessen the numbers within the camp. The North refused and the five returned to tell their comrades that there would be no exchange.

Literally hundreds of men died every day, and the camp staff could not keep up with the burials; bodies were simply stacked up until such time as they could be buried. All of this resulted in the situation arising where the inmates of the camp turned on one another, and gangs of marauding prisoners attacked their fellow inmates for food, clothing and shelter. These gangs were brought to Wirz’s attention and several inmates were hung for these crimes.

Towards the end of the summer of 1864, the Confederate army offered to release the prisoners if the Union sent ships to transport them away. The conditions at Andersonville were so horrendous that the Confederate army started moving prisoners away to try and ease the situation, but the Union did not send ships until the end of the year. In April of 1865, the Confederate forces surrendered and the camp at Andersonville was part of the surrender. Thirteen thousand men, out of the nearly 45,000 that had been incarcerated there, had died in the fourteen months that the camp had been in existence.

Both sides in this brutal battle between fellow countrymen were at fault and Andersonville sat at the middle of a perfect storm of coinciding issues. The Confederacy had nationalized many industries, and if they had done that to the food and lumber supply around Andersonville, Wirz would have had all the supplies he needed for the camp. The failure to do so left him in the untenable position of trying to purchase these supplies – at fixed prices and in a worthless currency that no-one wanted.

The North could have reinstated the prisoner exchange policy to try and alleviate the problems in the camp. Like most emotional issues it is incredibly difficult to lay the blame at the feet of one person, and while Wirz most certainly had crimes to answer for, he was not wholly to blame for the loss of life at Andersonville. Trying to distil this issue down to a few simple reasons is unacceptable, but the debate around who or what was to blame will keep historians busy for many years to come.

It is interesting to note that this trial set a precedent that was used in both World War I and II – that “following orders” was an unacceptable defense, especially when crimes against humanity were involved. This trial demonstrated that military orders cannot violate the common law rules of humanity, and in cases where this happens the soldiers involved will be held accountable for their actions.