Krukenberg gave his troopers two options: fight or return home to France. Some chose to fight.

One of the last Knight’s Crosses of the Iron Cross to be awarded in the Wehrmacht during WW2 was presented to a Frenchman: Unterscharführer in the Waffen-SS Eugene Vaulot.

Vaulot belonged to the “Charlemagne” Division, consisting of a group of French volunteers who fought on the side of the Third Reich against the Allies. This included fighting against their own country.

During the twilight days of the war in Europe, a pocket of these French fighters held on until the bitter end, refusing to surrender. They formed a pivotal final defense in what was considered a hopeless position. Many of them, including the aforementioned corporal, died doing their duty protecting the center of Berlin and the Führer’s Bunker.

The journey the French corporal and his comrades took to reach the carnage of the Reich’s capital was a rather unique one and began in the late autumn of 1944.

At that time, the French volunteers fighting in the Wehrmacht were formed into the 33rd Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS Charlemagne (1st French) and the Charlemagne Regiment on the “Wildflecken” parade ground where they trained under German leadership.

The unit came together by combining troops from other French groups fighting for the Wehrmacht. Many of the men in the newly created division were battle-hardened veterans who had fought alongside the Germans on the Eastern Front against the Soviets.

It did not take long for the division to reach a peak strength of around 7,500 men shortly after its inception.

The unit oozed symbolism and represented the very pan-European empire Hitler always envisaged. The name “Charlemagne” said it all.

The division’s crest portrayed a combination of both Germany and France: the fleur-de-lis and the Imperial Eagle of Germany joined as one in the footsteps of the great Frank Empire that once ruled all of Western and Central Europe over 1,000 years before.

It did not take long for the newly created Charlemagne division to face the enemy.

The leadership of the Wehrmacht gave the order in February 1945 to send these Frenchmen, who were still without heavy weapons and communications equipment, to Pomerania. Charlemagne soon found itself at Hammerstein, present-day Czarne, along with three divisions of the German army, where they were quickly encircled and defeated by Soviet armored divisions.

Only about a thousand Frenchmen under the command of SS-Brigadeführer Gustav Krukenberg managed to fight their way to safety.

On the night of April 23/24, 1945, Krukenberg (a German and fluent French speaker) received a call from the Army Group Headquarters at the Vistula. He was ordered to regroup his men into a storm division and help with the defense of Berlin.

Krukenberg gave his troopers two options: fight or return home to France. He was also entirely frank when he told his men that Charles de Gaulle was in the process of rebuilding a free France out of the chaos left behind by the retreating Nazis.

Over 60 percent of the men decided to return home. Those that remained knew that they could expect no leniency from the French people upon their return and chose to continue fighting for the Reich.

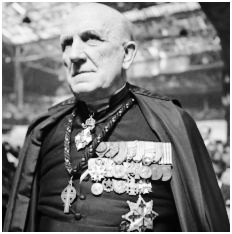

Approximately 400 Frenchmen volunteered to join Krukenberg in Berlin. They received further fiery oratory persuasion from the French divisional chaplain, Comte Mayol de Lupé, whose rhetoric espoused fighting to the death. This was the birth of the Sturmbataillon or Storm Battalion Charlemagne.

When the men of the newly formed Sturmbataillon Charlemagne arrived at Berlin, the eerie silence in the city surprised them––only the distant sound of Soviet cannons could be heard. The atmosphere was so different from the harsh conditions on the roads to the capital which had been awash with refugees and the confusion of an army on the cusp of defeat.

The Frenchmen continued their advance into the heart of the city that was supposed to be the capital of a thousand year Reich. It lay in ruins. It wasn’t long before they came across a group of Hitler Youths fighting the Soviets with Panzerfausts. Together, they managed to destroy some 14 enemy tanks and hold them off for 48 hours. It was a feat of extraordinary bravery.

The fighting continued for days with the Germans and their foreign contingents retreating in the face of superior fire and manpower. The fiercest melee occurred in the Berlin district of Neuköln. Members of Sturmbataillon Charlemagne accounted for over half of the over 108 destroyed Soviet tanks.

It was Unterscharführer-SS Eugene Vaulot’s finest hour in the heat of the Battle of Berlin near the Reich’s Chancellery. The Soviets hurled the bulk of their men and armor at their enemies in an attempt to bring the Nazis to their knees.

Vaulot destroyed six enemy tanks in the ensuing days while doing his duty near the Führerbunker. He was awarded the Iron Cross on April 29, 1945. A Soviet sniper killed Vaulot three days later.

Approximately 30 men of the once proud Sturmbataillon Charlemagne remained alive when Adolf Hitler committed suicide on April 30, 1945. That same day, Krukenberg gave the order to disband from the bunker complex.

Read another story from us: Brandenburgers – The Nazi Menace Behind Enemy Lines

Many of the Frenchmen surrendered to the Soviet Army near the Potsdamer rail station. Others fled west and managed to give themselves up to British forces at Bad Kleinen. However, many of the men made it back to France where they were apprehended and placed in POW camps––eleven or twelve are believed to have been shot by the French authorities as traitors.